Remembering D-Day, 1944

North Woodmere resident was part of the Allied invasion

June 6 marks the 75th anniversary of the Normandy landings, famously known as D-Day. As the years have passed, the number of living World War II veterans has declined. The Veterans Administration estimates that within 20 years, there will be no living veterans of that war.

One North Woodmere resident can recall the European invasion. Vincent “Jimmy” Lijoi, 93, was born on Oct. 30, 1925, in Italy. He and his family immigrated to the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn when he was 10, and he grew up less than 10 blocks from Ebbets Field, the home of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

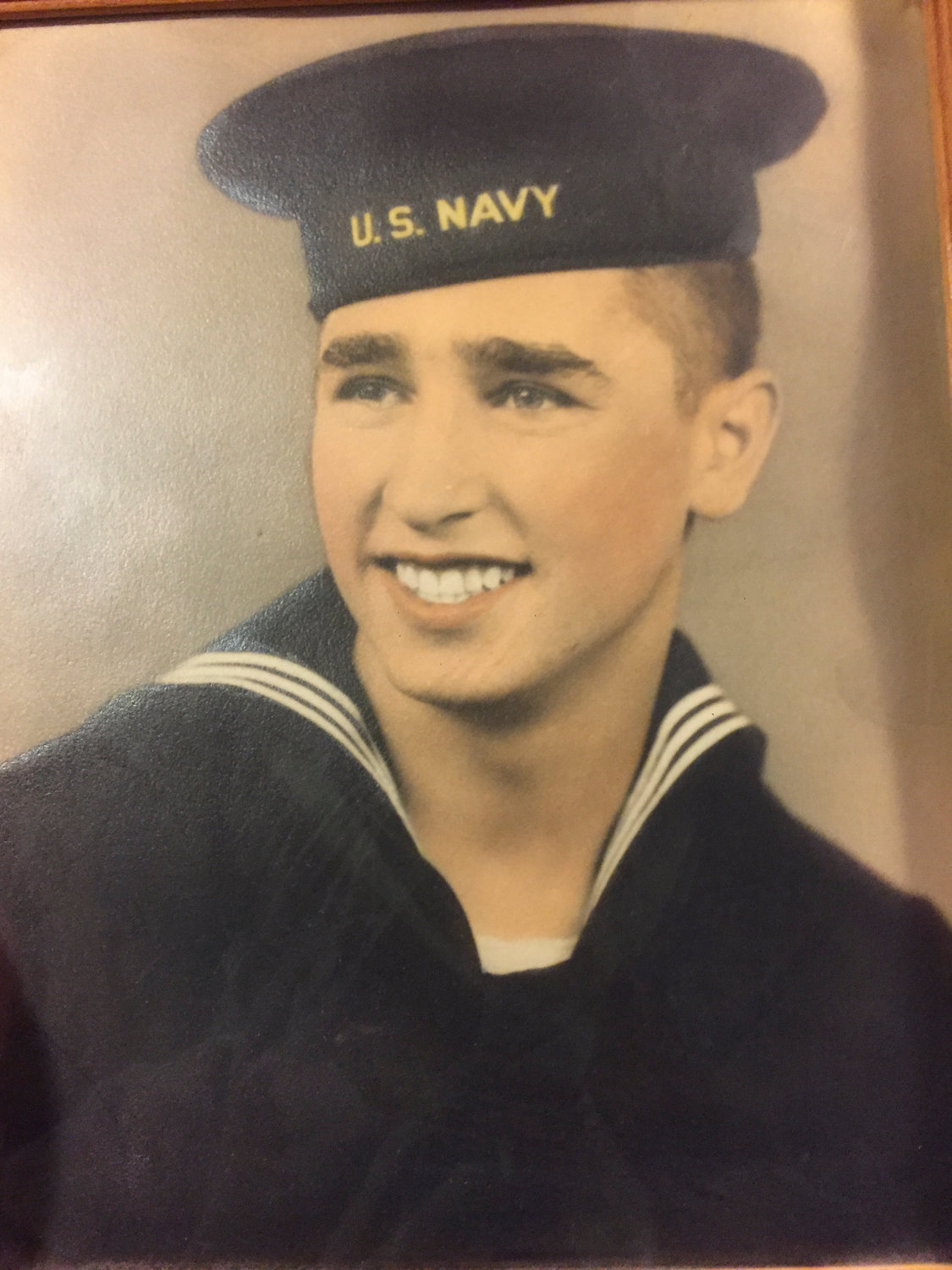

Lijoi was a U.S. Navy seaman 1st class aboard the USS Landing Ship Tank 510 as an 18-year-old on D-Day. He had been drafted in October 1943, and chose the Navy because he liked the uniforms. “I wanted to join, but my mother didn’t want to sign the enlistment papers for me,” said Lijoi, who was featured on a 2018 “Today Show” segment on the passenger ferry Cape Henlopen, formerly the USS LST 510. “It turned out that I was drafted about a week or two after my mother refused to sign the papers.”

By June 1944, the ship was preparing to head to France. The weather was bad on June 5, which prompted the invasion to be delayed a day. A history of the ship compiled by Zach Morris detailed the mood of the crewmembers before the invasion. “So at 3:55 a.m., June 6, the 510 again went . . . embarking on a pilgrimage that will always live in the minds of the men present, that will forever be written in the history books as the greatest invasion ever undertaken up to that time,” Morris wrote.

D-Day was the largest seaborne invasion in history, and it turned the tide of World War II in favor of the Allies. Roughly 24,000 American, British and Canadian troops landed on the beaches of Normandy at midnight on June 6. They were followed by Allied infantry and armored divisions landing on the coast of France at 6:30 a.m. The soldiers were met with heavy fire from German forces, and 4,414 Allied troops were confirmed dead from the invasion, which jump-started the liberation of France — and Europe — from Nazi Germany.

As the 510 headed toward Omaha Beach, Lijoi recalled, he realized the magnitude of what was taking place. “I saw bodies and life jackets floating in the bloody water,” he said. “It was terrible.” Also aboard the ship were 200 men from the 29th Infantry Division, most of whom died that day. “I don’t know the exact number, but there were not many survivors from that infantry,” he said. “They were the first line of defense that day, and they paid the ultimate price.”

Fellow LST 510 survivor Thomas Patton had one of the toughest jobs: He was in charge of getting wounded soldiers off the beaches. “I was a coxswain on a small boat,” Patton told Morris compilation. “I had to go on the beach and collected the wounded.” A coxswain navigates and steers a boat. Patton, who lives in New Jersey, did not return a call seeking comment.

There were eight doctors aboard the ship. “I saw a surgeon amputating three or four arms and four legs over a span of a couple of days,” Lijoi said. “He had to cut them because they were so damaged.”

After the invasion, Lijoi said, the 510 made 28 trips from France to England with wounded soldiers, and carried supplies to France on the return trips.

On Feb. 5, 1945, the ship was crossing the English Channel, heading toward England on a foggy night. Lijoi was the ship’s bow lookout on the port side. He said he heard something that sounded like another ship. “I had good eyes and ears back then,” he said. “For some reason, our radar wasn’t picking up the other ship.” Lijoi was right, and the ship ahead was the SS Chapel Hill Victory, a U.S. cargo ship.

Nearby was 17-year-old Mack Henry Warren, who had joined the 510 crew roughly two weeks earlier. “I yelled to the kid to run for his life, since the ship was coming right at us,” he said. “But he just froze and was killed instantly.” The two ships collided head-on, according to Lijoi.

The wrecked LST 510 was towed to Falmouth, England, and never saw battle again. It sailed back to the U.S. on June 7, 1945, a month after Germany surrendered. In 1983, the ship was converted into a passenger ferry named Cape Henlopen. It crosses the Long Island Sound, between Orient Point and New London, Conn., every day of the week.

Lijoi was discharged in late 1945 and briefly returned to Brooklyn before moving to Hollis, Queens, and eventually settling in North Woodmere, where he has lived for roughly 40 years. He worked as a butcher from the time he came home until he retired 20 years ago. He married twice, and his second wife died roughly a decade ago. They had been together for 20 years.

Despite her absence, Lijoi said that he is content with life. “I got to play a part in saving the world,” he said. “Thank God for America.”

Syd Mandelbaum, commander of Lawrence-Cedarhurst American Legion Post 339, has known Lijoi since 1980, through Five Towns Kiwanis. “Whoever meets Jimmy loves him,” Mandelbaum said. “He’s so humble, even though what he did during the war should be magnified.”

Mandelbaum said that June 6 has a special meaning for him as well. “The war ended, and as a child of Holocaust survivors, my parents were liberated on May 8, 1945,” he said. “It would not have happened without D-Day and Jimmy.”

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy