Can Arena Partners do it? Yes and … maybe

Belmont financing and solution to community opposition still murky

Part two of a two-part story

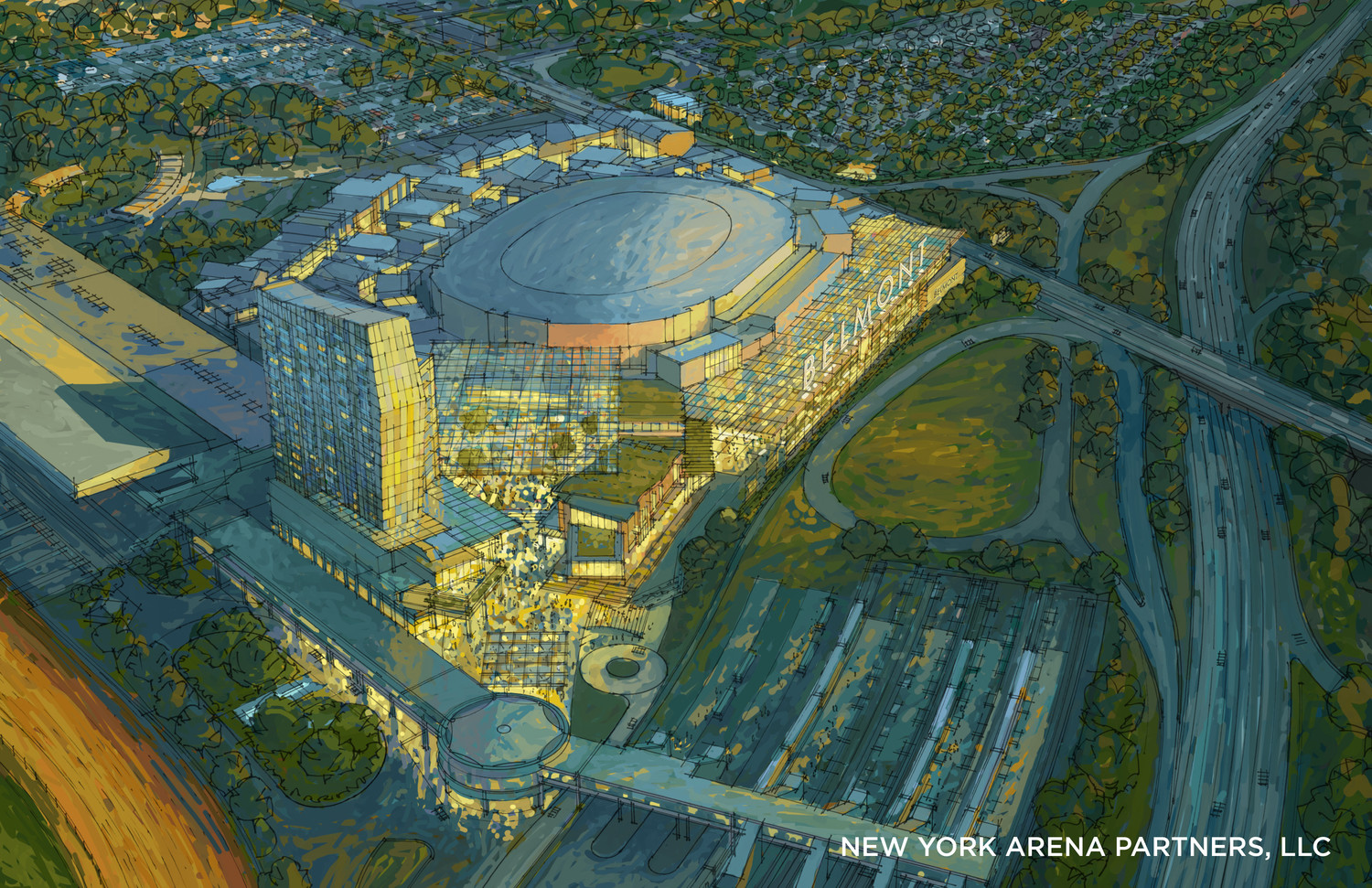

Can Arena Development Partners build an 18,000-seat hockey stadium in time for the opening puck of the 2021 season? Yes.

All the players on the build side of the equation are experienced. The lead architect played the same role at both the Mets’ Citi-Field and Yankee Stadium in New York, as well as Las Vegas’ T-Mobile Arena and the Pittsburg Penguins’ PPG Paints Arena. Those stadiums, though different in size, configuration and cost took roughly three years from groundbreaking to opening day.

The issue has never been solely a question of practicalities. From the start, three significant obstacles have stood in front of the Belmont Park project, and to date, none of them have been addressed generally, let along comprehensively.

The issues include:

- The cost and timetable for construction of the supporting infrastructure that the project will require.

- Significant community opposition that will almost certainly include legal action, unless Arena Partners addresses various groups’ concerns.

- Financing.

To date, all that is known about this stadium’s projected cost is a number: $1 billion. On the infrastructure side, estimates for the Long Island Rail Road link alone run into nine figures. No one has yet mentioned the possible cost of widening streets or upgrades to parkways. Both the Yankees’ and the Mets’ stadiums were built near existing facilities and in densely populated New York City neighborhoods and had the same access to subways and parkways as their former homes. Arena Partners will be starting essentially from scratch, because according to experts, the means simply do not currently exist to deliver 18,000 spectators to 150 events per year.

Forbes assigned a value of $385 million to the Islanders in late 2016, and team partner Jonathon Ledecky found no takers when he attempted to borrow $500 million against a 15 percent equity stake in the team earlier this year. Cuomo, Ledecky and the Islanders all have insisted the project will neither receive nor require any public financing, but community activists are skeptical.

In addition to transportation upgrades, the new facility will require additional police and fire protection, not to mention the loss of revenue if the state were to lease the 43-acre parcel it persistently described as worthless on the terms the governor proposed: a 49-year lease totaling $40 million, or slightly more that $800,000 per year.

It’s also unclear whether tax revenue from the stadium would flow into public coffers, no matter what valuation is placed on the land. Those funds could be used to help pay for the development itself in the form of PILOT bonds. PILOT bonds, or payment in lieu of taxes, allow private developers on public land to apply tax assessments in exactly this way, according to an analyst at Moody’s Investor Services. He was quick to add that stadiums can be financed in dozens of ways, and that he had no special knowledge of any Belmont Park deal. But if PILOT bonds were part of the financing, the loss to local school districts could be enormous.

That same land could generate property taxes for local schools if the land were used for affordable housing that the community desperately needs, according to local activist Tammie Williams, who was quick to qualify this as only one of many possibilities more beneficial to the community.

She said the project could also include small manufacturing or other forms of “smart” development. This give-away of land potentially far more valuable than the current sticker price is only one of many grievances that Empire State Development, the property’s current owner, and Arena Partners have yet to address, Williams said.

The stadium’s partners still have not held substantive discussions with members of the local community, she said. The listening session that took place at Elmont Memorial High School on Dec. 10 allowed for only limited discussion on a set number of topics, with written questions submitted in advance. Williams, as well as representatives of various community groups, such as the Parkhurst Civic Association, contend that such constraints violate the conditions of Article 78 of the Urban Development Corporation Act.

Ultimately, whether the lenders are private or public, they will likely use the same criteria in assessing the project’s viability. Broadcast rights, luxury boxes, naming rights and branded souvenirs may be profitable sidelines, but guarantors look for a steady, predictable source of revenue.

The prestige of the franchise and the size of the market are important factors, according to a Moody’s report comparing Queens Field (the official project name for Citi-Field) and Yankee Stadium. The make-up of the project’s management team and its experience also play a role. In the end, though, both Citi-Field and Yankee Stadium were 100 percent secured by revenue from projected attendance at games, according to the same report. Any significant drop in that attendance could cause the stadium’s credit to be downgraded.

Conditions in the covenants could require the team to increase its debt service coverage, or, in some cases, to provide an immediate cash infusion in order to stave off steeper downgrades or even a default scenario.

Both the Mets and the Yankees have had recent championship seasons. The Mets guaranteed 100 percent of their initial debt-service coverage in advance, and both have had steady attendance for several years that is more than adequate to meet requirements for coverage. Despite all these positives, Citi-Field carried a junk rating until last year, and the Yankees, among the most storied franchises in American sports, have only just managed to maintain a low investment-grade rating for “the house that Ruth built.”

The Islanders, by contrast, haven’t had a championship season since the 1980s, and they have the worst attendance record in the NHL. At an average of 11,600 per game in 2017, they are potentially looking at many empty seats at Belmont Park, unless Long Islanders begin to return to the team that many had to forgo when it moved to Brooklyn because it was just too far and too hard to get to.

Last week NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman paid a low-key visit to Nassau Coliseum, reportedly to determine whether it could house the Islanders while the Belmont stadium is constructed.

47.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

47.0°,

Mostly Cloudy