Elmont to officials: Why are we sick?

Despite regular monitoring, elevated cancer rates stymie residents

No matter how the figures are calculated, Elmont residents have higher cancer rates than people in surrounding communities. They want to know why. It’s a question they have been asking for a long time.

The Nassau County Department of Health commissioner, Dr. Lawrence Eisenstein, told the Herald last week that the number of new cancer cases in Elmont was “somewhat higher than expected.” But it was not so egregious as to warrant more than the normal concern that any responsible person ought to demonstrate with regular check-ups and screenings.

While Eisenstein and department epidemiologist Celina Cabello explained how the expectations were calculated, they still left certain questions unaddressed: Why are expectations higher for Elmont than for its neighbors? And why are the actual numbers higher still?

Eisenstein said that the calculations are carried out by the state, which also maintains the cancer registry. The calculations entail complex volume weighting that factors in age, ethnicity, sex and genetic predisposition, among other considerations, Cabello added.

By those criteria, then, the county department was told to expect 153 new cases of prostate cancer in Elmont in the five-year period between Jan. 1, 2008, and Dec. 31, 2013. The actual number was 226 cases — a difference of 47.7 percent. In the same period, neighboring Franklin Square was told to expect 107 new cases. The number of observed cases was 114. That difference was 6.2 percent. In Valley Stream, the numbers were 157 and 164, or 4.4 percent.

The numbers themselves do not tell the entire story. Besides the factors that help the state in its estimates, not all cancers affect all segments of the population equally. And much of how humans acquire cancer remains unclear.

Prostate cancer is typically a late-onset disease. “Cancer can be in the body for years before we see it,” Cabello said, “and prostate cancer affects a higher number of African-American men than other men.” The incidences of breast cancer are likewise elevated among African-American women, she added. Breast cancer also affects a small percentage of men (more than 2,100 nationally in 2014, the last year for which complete figures are available). Since Elmont has a larger African-American population than Franklin Square, higher figures for these two types are to be expected, she said. This, however, still did not explain Elmont’s discrepancy between expected and actual cases.

Every area reported larger numbers than expected, because Nassau County as a whole has higher cancer rates than other counties, according to Eisenstein. But while Franklin Square is smaller both in population and percentage of African-Americans, Valley Stream is much closer in demographic profile to Elmont. Yet the number of observable cases for prostate cancer was 27 percent lower.

All of this assumes the data can be taken in isolation, and that the data for Nassau County is roughly comparable to New York state as a whole. But even a side-by-side comparison with statewide statistics, which both Eisenstein and Cabello said would give a more accurate picture, showed Elmont to be higher, both in observable cases and in projected new cases per 100,000.

For example, the incidences of prostate cancer for one year, 2013, showed Elmont with a rate of 298.4 cases per 100,000 population, versus 127.3 for the state as a whole, and breast cancer cases equivalent to 203.3, versus the state’s 132.2. The figures for Elmont had to be extrapolated from the state registry’s five-year figures and adjusted for population, so the results are likely inexact. And the demographics for the community have shifted rapidly in the past half-dozen years, so that even government agencies such as the U.S. Census and the Environmental Protection Agency have quite different snapshots that could affect the accuracy of the data for 2013, let alone 2018.

Whatever the explanation, cancer rates are elevated in Elmont, according to state data. And ethnicity doesn’t fully explain the disparity, either. At one time, Elmont had a population that was nearly 50 percent African-American. But shifts in demographics put those figures closer to one-quarter, according to EPA figures derived from the most recent census. That is roughly the same level as in Valley Stream.

Genzale

The causes of these disparities are not clear at present. The data and the facts on the ground present too many anomalies to infer any cause. But in the past three decades, local residents have referred persistently to two concerns. The first is the proximity to hazardous waste sites, and the second is the quality of their water.

In 1981, the county Department of Health inspected the Genzale Plating Co. Inc., located across Hempstead Turnpike from Elmont in Franklin Square. The company had been in business at the same half-acre location since 1915, according to the EPA. Its main business in 1981 was electroplating small metal parts, such as automobile antennas, bottle openers and components for ballpoint pens. Part of the process entailed the use of volatile organic compounds and heavy metals, such as cadmium, chromium and zinc.

From 1915 until sometime in the mid-1950s, when the plant was connected to the county sewer system, Genzale discharged its liquid runoff into two to four leaching pits (descriptions vary as to the number, even in official documents). These pits were not sealed completely to contain the chemical effluents discharged into them, the EPA states on its website. As a result, the contaminants flowed into two aquifers. Seven supply wells were located within a mile of the site itself, and water from the aquifers was used for domestic consumption in the areas on both sides of the turnpike.

The DOH investigators found that the company was still discharging wastewater into the leaching pits at the time of the inspection and ordered the company to stop. Although Genzale did stop, it never undertook any work to clean up the resulting sludge, according to the EPA.

The state Department of Environmental Conservation investigated the company in 1983 and placed it on the National Priorities List, thus designating the location as a Superfund site. From 1981 to 2000, when Genzale closed its doors, various local and federal government agencies monitored the cleanup of the sludge beneath the leaching tanks, removing some 30,000 pounds of contaminated dirt in the process, and replacing it with sand.

The EPA advanced various ideas to remediate the aquifers as well. One plan required the drilling of injection wells to flush out the aquifers with clean water. The plan would take an estimated 14 years to bring the aquifers back to their pre-1915 states. Another plan was simply to allow the aquifers to clean themselves through the natural flow of water. It was estimated that process would take 18 years, at a much lower monetary cost.

Genzale was unable to pay for any of the site remediation, which, despite its Superfund status, was apparently never tagged as a health risk to local residents. Even the wells continued mostly in use, except for the occasional shutdowns that Long Islanders have grown used to. By 2005, EPA officials declared the aquifer and the Genzale site safe. No evidence could be found of any ongoing cleanup at the site after that. Water quality reports for the Western Nassau Water District from 2002 to 2016 — the last year available — did not show any testing for the VOCs or heavy metals known to have been used by Genzale.

Safe water?

In 2010, three local activists met with former state senator Craig Johnson at Elmont Memorial Library to discuss water quality. The water coming out of people’s taps was roughly the same color as coffee.

“Our water supplies come from four wells along Elmont Road,” Joyce Stowe, of the Tudor Civic Association, said at the time. “In the area, there is runoff from gas stations, dry-cleaning businesses, pesticides, that fall into these wells. I take it that the [Belmont] racetrack runoff goes there, too.”

Mimi Pierre-Johnson, of the Argo Civic Group, remembered the meeting and commented on the improvements since then. “My water isn’t coffee-colored any more,” she said, laughing. “Now, it’s more a greenish-yellow.” Like most residents, she doesn’t drink anything that comes out of the tap. “My water is all filtered.”

The county health department regularly monitors water quality, as the state mandates, and it sends out annual reports to residents, according to Eisenstein. None of the dozen or so local residents surveyed informally could remember receiving the reports, and all were aware of the ongoing water issues and had a vested interest in seeing them resolved. But the reports did look like the sort of mail everyone gets from government and may simply have escaped attention. Copies for reports from 2002 to 2016 are available online.

Mimi Pierre-Johnson, who also attended the 2010 meeting as president of the Argo Civic Association, was asked whether she recalled other local sources of pollution at the time. “The streets were lined with gas stations,” she said, "...and there were dry cleaners, too.”

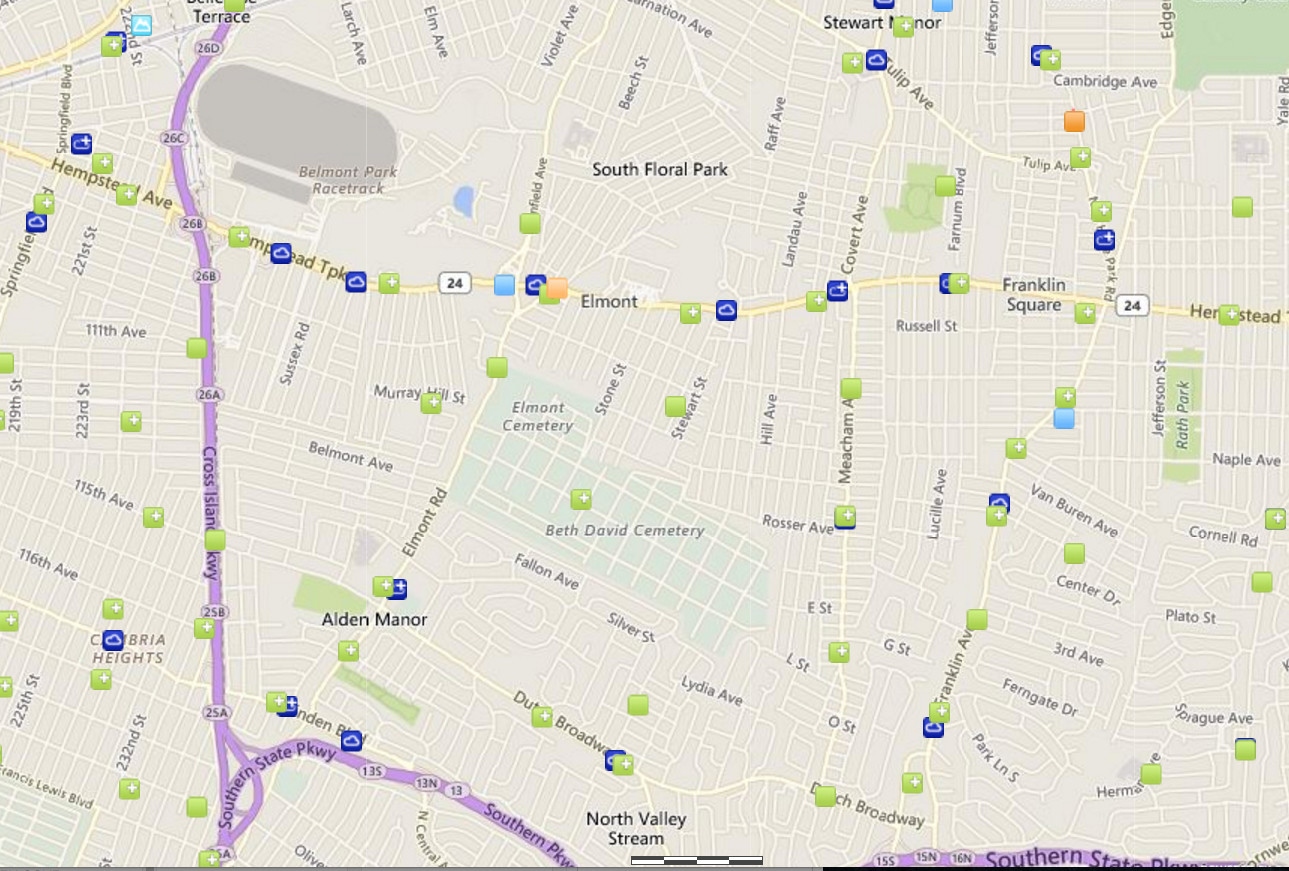

An EPA map of the area confirmed Pierre-Johnson’s memory and showed nearly 80 hazardous waste sites throughout Elmont, especially along Hempstead Turnpike, Elmont Road and Franklin Avenue. Other waste sites dot the map of the community and still run along Elmont Road — some remediated, and some not.

No causal link has been established between the community’s elevated cancer rates and the water, the Superfund site or any of the waste sites. And Franklin Square has a number of waste sites, too, as well as the Genzale Superfund site. Residents have nevertheless been fighting for clean water for decades.

Patrick Nicolosi, former president of the Elmont East End Civic Association, said at the 2010 meeting that he first complained in 1977. He’s still fighting, albeit on more than one front.

“We moved here from Astoria in 1967,” Nicolosi said last week. He, too, remembers the meeting. “After that, nothing happened.”

Johnson was defeated in his re-election bid that year, and his successor was less responsive to the issue. Then, in 2013, Nicolosi began to have health issues. “I just wasn’t feeling good, so I went to my doctor.” Eventually, he was diagnosed with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Hashimoto’s is a form of hypothyroidism — essentially a non-functioning thyroid gland. The gland helps regulate the body’s metabolism, but the disorder is easily treated with medication. “I didn’t get any better. My son’s a doctor, so eventually, I went to him,” he said. Finally, in 2016, he was told he had medullary thyroid cancer, an extremely rare form of the disease, and needed surgery.

Nicolosi is not alone in his fight. On his short block of roughly a dozen houses, four other residents are currently being treated for various forms of cancer. One, Lauren Struzzieri, a 38-year-old mother of two, has been battling non-Hodgkins lymphoma since 2016, when she was pregnant with her daughter. “If it was just me, I’d probably think it was just my time, or my bad luck, you know? But there’s Pat and all the others.”

Nicolosi agreed. “I’ve made my peace. But I’m thinking about my grandchildren. What about them?”