Glen Cove resident wants political leaders to learn from the past

Cites WWII internment of Japanese-Americans

On a wall in Kim Christian's home is a display of 12 photographs that are evidence of a culturally diverse family tree. In the middle are her parents, Bob and Francine Machida. Bob’s father, a Japanese immigrant, and his mother, a second-generation Japanese-Irish woman, are at the top of the tree. In another frame are Francine’s parents, both Italian-Americans. Below hangs a picture of Kim and her husband, Amol, who is of Indian descent. Below that is a photo of their children, Chloe and Owen. There are also pictures of the Machidas’ son, Chad, and his wife, Emily; and their daughter, Madison.

To the Machidas, this wall’s importance is twofold. It shows not only the history and future of their multicultural family, but also the increasing diversity of the U.S. population.

“My three grandchildren — that’s the future of America,” said Bob Machida, 72, of Glen Cove. “The future of America is going to see people being proud of their cultures, but there’s going to be a lot more of an integrated society sharing cultures, sharing ideas, sharing technology.”

Machida is passionate about cultural coexistence in America, specifically because the immigrant and nonimmigrant members of his family experienced one of the country’s darkest periods. In February 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, forcing the relocation and internment of all Americans of Japanese ancestry. Families in the western U.S. who were forced to relocate were allowed to take with them only what they could carry. They had to sell their homes and belongings and give up land and jobs. The order affected 117,000 people of Japanese descent.

“One of the great ironies of the internment was that many young Americans of Japanese descent enlisted in the U.S. Army,” said State Assemblyman Charles Lavine.

The following year, the 422nd Regimental Combat Team was formed from a group of Nisei — second-generation Japanese-Americans — to fight in the European theater. The group joined the 100th Battalion, and went on to become the most decorated unit, for its size and length of service, in American history.

Toward the end of the war, the internment camps were evacuated, but not many internees returned to their hometowns.

Machida’s parents lived on the East Coast, where they avoided internment, but they were still required to report monthly to Washington, D.C., to explain why they should be permitted to stay in the U.S. But his aunt and her family, who lived in California, were sent to inland internment camps.

In 1980, the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians was appointed by Congress to investigate Roosevelt’s executive order. It concluded that the internment was the result of “racial prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”

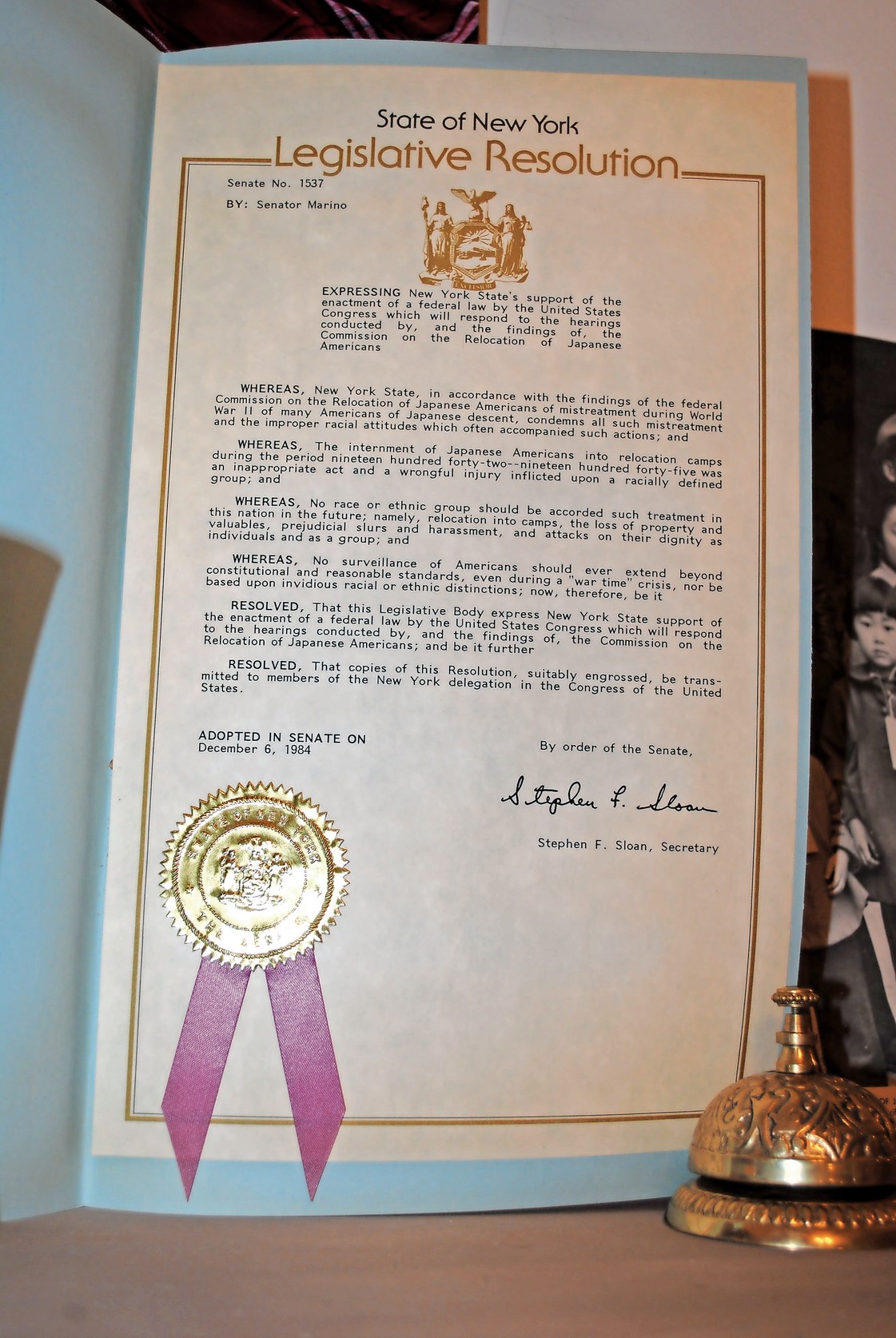

While those who were interned mostly kept their experiences to themselves, the generation that followed them, which included Machida, did not. In 1984, Machida worked with then Democratic State Assemblyman Lewis Yevoli and Republican Sen. Ralph Marino to draft a resolution that backed the commission’s findings, and asked for an apology and compensation for those who had been interned. It passed the State Legislature unanimously.

“I felt that Bob Machida was absolutely correct in bringing it to our attention,” said Yevoli, who represented Glen Cove at the time. “These people were not treated well. These people were innocent people.”

Machida, an elementary school teacher, also gained the support of the 770,000 members of the United Federation of Teachers in 1985 to back the commission’s findings.

Three years later, U.S. Sen. Alan Simpson, a Wyoming Republican, introduced a bill in the Senate, while U.S. Rep. Norman Mineta, a California Democrat who was himself interned, brought a similar bill before the House.

President Ronald Reagan eventually signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which granted reparations to previously interned Japanese-Americans in the form of a written apology and $20,000.

“Bob Machida’s work and the work of others to try to right a terrible wrong is extraordinarily noteworthy,” said Lavine, who has known Machida for many years. “Japanese-Americans being placed in camps was wrong, and was in fact un-American, so in the years that followed, the U.S. government and New York state have certainly acknowledged that wrong, and have taken steps to make sure that never again occurs.”

Machida said he believes that the country needs to remember what happened in the past, and learn from it moving forward. He said that the bipartisan support for the state and federal legislation was an exemplary lesson that today’s political leaders can learn from.

“This is what cooperation is about,” he said. “You can’t cooperate on everything, but you can certainly try. People want to be here because they know about a society that cherishes its freedom, its independence and the fact that they can get ahead in life. That, to me, says a lot about what America stands for.”

48.0°,

Overcast

48.0°,

Overcast