A fighter until the very end

Luis Alvarez is the Oceanside/Island Park Herald's 2019 Person of the Year

Luis Alvarez “marched to his own beat” and liked to stay under the radar, recalled his oldest brother, Phil Alvarez.

He didn’t get excited about too many things, but he loved fishing.

When his brothers bought their first cars as teenagers, a young Lou, as loved ones called him, came home with a motorcycle.

He only smiled when the emotion was genuine, and he only spoke when he really meant it.

“When he had something to say, you listened,” Phil said. “You never had to guess what was important to him and what wasn’t. He didn’t mince his words, and he didn’t talk unless he had something to say.”

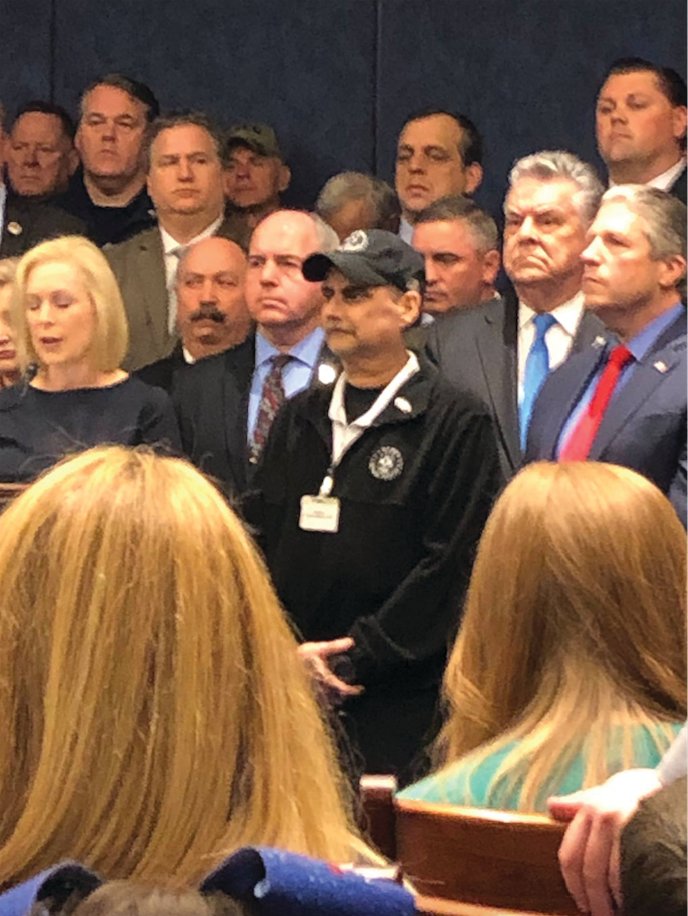

That’s exactly what occurred on June 11, when Alvarez, the Herald’s 2019 Person of the Year, testified before the House Judiciary Committee in Washington, D.C., all but demanding that the federal government replenish the 9/11 Victim Compensation Fund. Suddenly, the Oceanside man who never wanted any attention was on television alongside comedian Jon Stewart, addressing members of Congress and the nation.

He pleaded with lawmakers to provide other ailing 9/11 first responders the same financial comfort he had since he was diagnosed in 2016 with Stage 4 colorectal and liver cancer, which was correlated to his time spent at ground zero. Three weeks after his testimony, he died at age 53.

“Once he believed in something, there was no wavering in his demeanor and in the things that he did,” Phil said. “If he felt it was right or believed in it, he was in 100 percent.”

Alvarez was born in Havana, Cuba, and moved to Queens with his family before turning 2. He was the third of four children. In addition to Phil, Lou is survived by his sister, Aida Lugo; a brother, Fernando; his mother, Aida; his father, Felipe; his wife, Alaine Parker Alvarez; and sons David, 28, Tyler, 20, and Benjamin, 16.

Alvarez graduated from McClancy Memorial High School in Elmhurst. When he turned 18, he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps. After his service, he joined the NYPD, shortly before his 25th birthday.

Alvarez began his tenure in the NYPD by working uniform patrol in the 108th Precinct in Long Island City. He then transferred, working undercover for the narcotics bureau and eventually joined the Bomb Squad.

“We were all amazed by the work he was doing,” said Brian Senft, Alvarez’s former partner in the Bomb Squad. “From the beginning, we were all looking up to him.”

He was “one of the best technicians in the Bomb Squad” because of his fearlessness and willingness to learn, Senft said. That dedication spread to the entire team, he added.

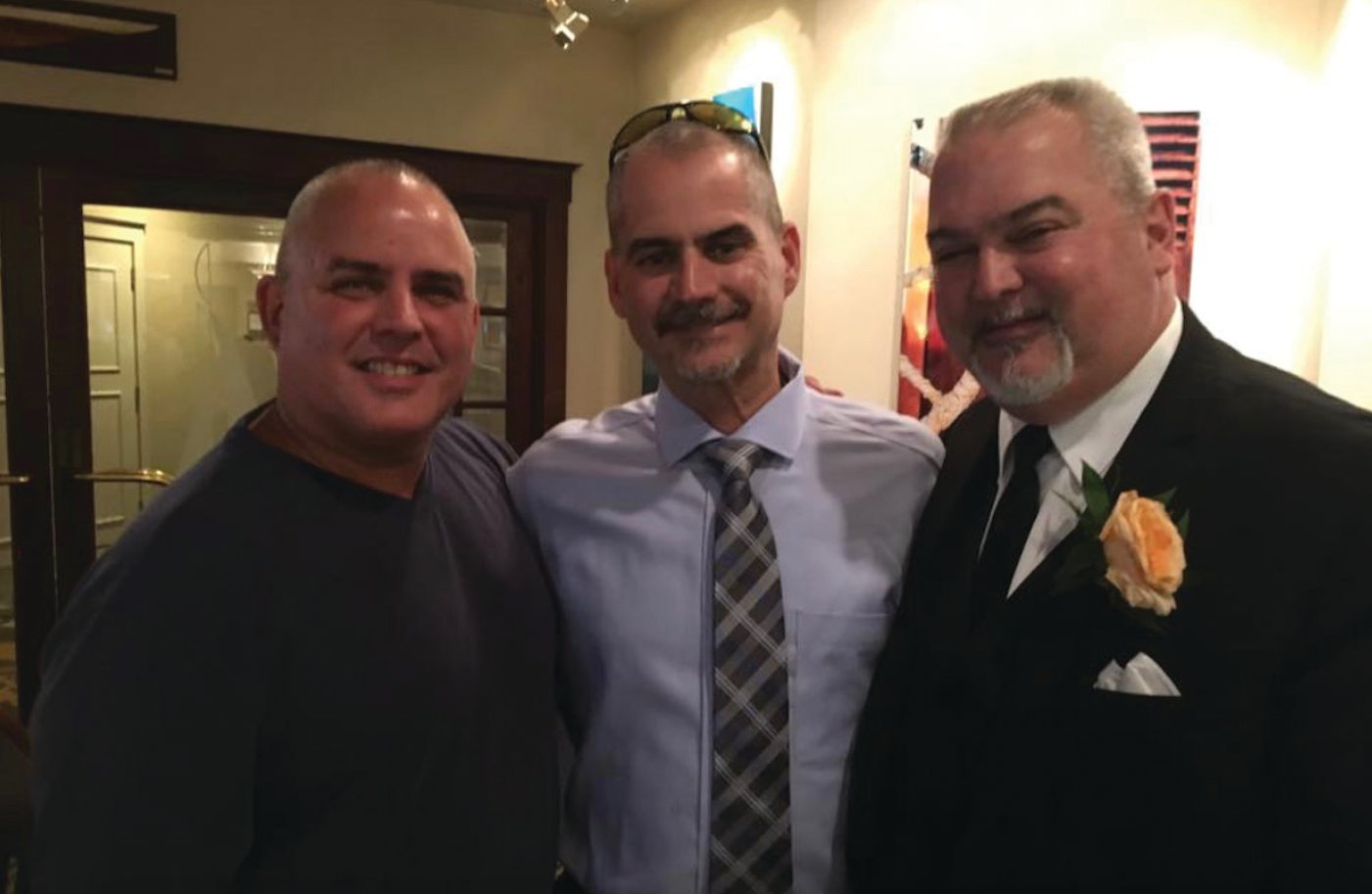

Senft met Alvarez in 1990 in the police academy, and the two became best friends while working on the narcotics team together. “He was a very caring person,” Senft said. “He was very soft-spoken. He didn’t have a bad thing to say about anybody, and he got along with everybody.”

In 1993, Alvarez met Alaine — “Lainie”— at a bar in Rockville Centre. She had grown up in Baldwin. The two started dating, and got married on Oct. 1, 1995. They moved to Oceanside in 1998.

“He was funny,” Lainie said. “He knew how to make people laugh. When he smiled, the whole room smiled with him. He wasn’t stoic, but with his job and everything he was very serious sometimes.

“. . . He was a very good father,” she added. “He always made sure their needs were met. He would take them to the movies and out to eat and do what he could when he had time off.”

After the attacks, Alvarez spent three months sifting through the rubble at ground zero. He didn’t speak of it, though, his family noted, as did Senft.

Around this time, Phil noticed his brother was getting more tattoos. Some included the Arabic letters for “Never Forget” on the back of his neck, bomb squad symbols on the backs of his hands, a unicorn on his chest and a tiger on his right arm. “I thought maybe that was his way of grieving 9/11,” Phil reflected.

Alvarez retired in 2010. His cancer diagnosis came six years later. For Alvarez, this was something worth talking about. He started posting about his chemotherapy treatments on social media and raising awareness of cancers caused by exposure to debris at ground zero.

He also contacted many of his peers through a private Facebook group called Club 23, named in honor of the 23 NYPD officers who died instantly when the twin towers fell. There are 15,000 members of the group, and he used the platform to urge his fellow officers to get examined and to join the Victim Compensation Fund. During chemotherapy sessions, he spent hours in a chair at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in Manhattan and blogged about his experience in the group.

Because Alvarez contacted first responders who worked at ground zero, some visited their doctors, got checked for cancer and detected it early, Senft explained. “I think that’s a great legacy,” he said. “I’m real proud of what he’s done.”

When he was asked to testify before Congress to help restore the fund, there was no question about it, Phil recalled. At that point, Alvarez had been through 68 rounds of chemotherapy. “I said, ‘Are you sure you’re up for this?’” Phil recalled. “He said, ‘If you don’t take me, I’ll get someone from the police force to take me.’ He was that adamant about going.”

Because Alvarez had a pump implanted in his abdomen to treat his liver, he couldn’t travel on an airplane. So Phil drove him from Long Island to Washington D.C.

“It was horrible,” Lainie said. “I mean, I was proud of him, but I was also angry because . . . knowing how sick he was, I knew it was going to take a toll on him.”

During the car ride, Alvarez was nervous. This wasn’t in his nature, Phil said, and he didn’t want to let anyone down. At the same time, Alvarez’s motto was always “Still here, still breathing, still fighting.”

“Less than 24 hours from now, I will be serving my 69th round of chemotherapy,” Alvarez told the members of the Judiciary Committee. “I should not be here with you, but you made me come. You made me come because I will not stand by and watch as my friends with cancer from 9/11, like me, are valued less than anyone else.”

About a week later, Alvarez was admitted into hospice. On June 29, he died peacefully, surrounded by friends and family. “He died knowing that most likely the VCF bill would pass, and he was at peace with that,” Phil said. “He knew he had given it all he could.”

A month after his death, on July 29, President Trump signed into law the “Never Forget the Heroes: James Zadroga, Ray Pfeifer and Luis Alvarez Permanent Authorization of the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund,” which was named in honor of three NYPD officers who died of 9/11-related illnesses. The measure restored the funds and will enable claims to be processed into 2090.

Alvarez most wanted recognition from his three sons. “He wanted his legacy to be not with the country but with his boys, that they knew their father never gave up,” Phil said. “Once he put his mind to something, he did not quit until he was done.”

Alvarez was always busy, fiddling with tools and working with his hands, his wife noted. When he got sick, he took up wood carving, and designed wooden plaques for friends and family.

He made about 150 different wooden creations, many of them dedicated to fellow police officers or making reference to 9/11. One of them read, “I don’t know how I’m going to win, but I do know I’m not going to lose.”

Mike Smollins contributed to this story.

49.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

49.0°,

Mostly Cloudy