Oceanside World War II veteran recalls service, life after the war

U.S. Army Pfc. Milton Seitman waded through the cold Atlantic off the shore of Normandy, France, on July 8, 1944, with his rifle held high above his head. He didn’t know what to expect, but when he got there, everything was quiet.

Thirty-two days earlier, the stretch of beach codenamed Omaha by Allied war planners had been the site of the D-Day invasion, during which roughly 20,000 soldiers had been killed — the beginning of the end for Germany, and World War II.

Seitman, a switchboard operator for the Army Signal Corps, was there to establish an Allied command post on the newly captured beachhead. Of the roughly 16.1 million Americans who took part in World War II, it was estimated that one in nine served in combat roles. Seitman was one of the tens of thousands of personnel supporting the front lines from the rear as they pushed east toward Berlin.

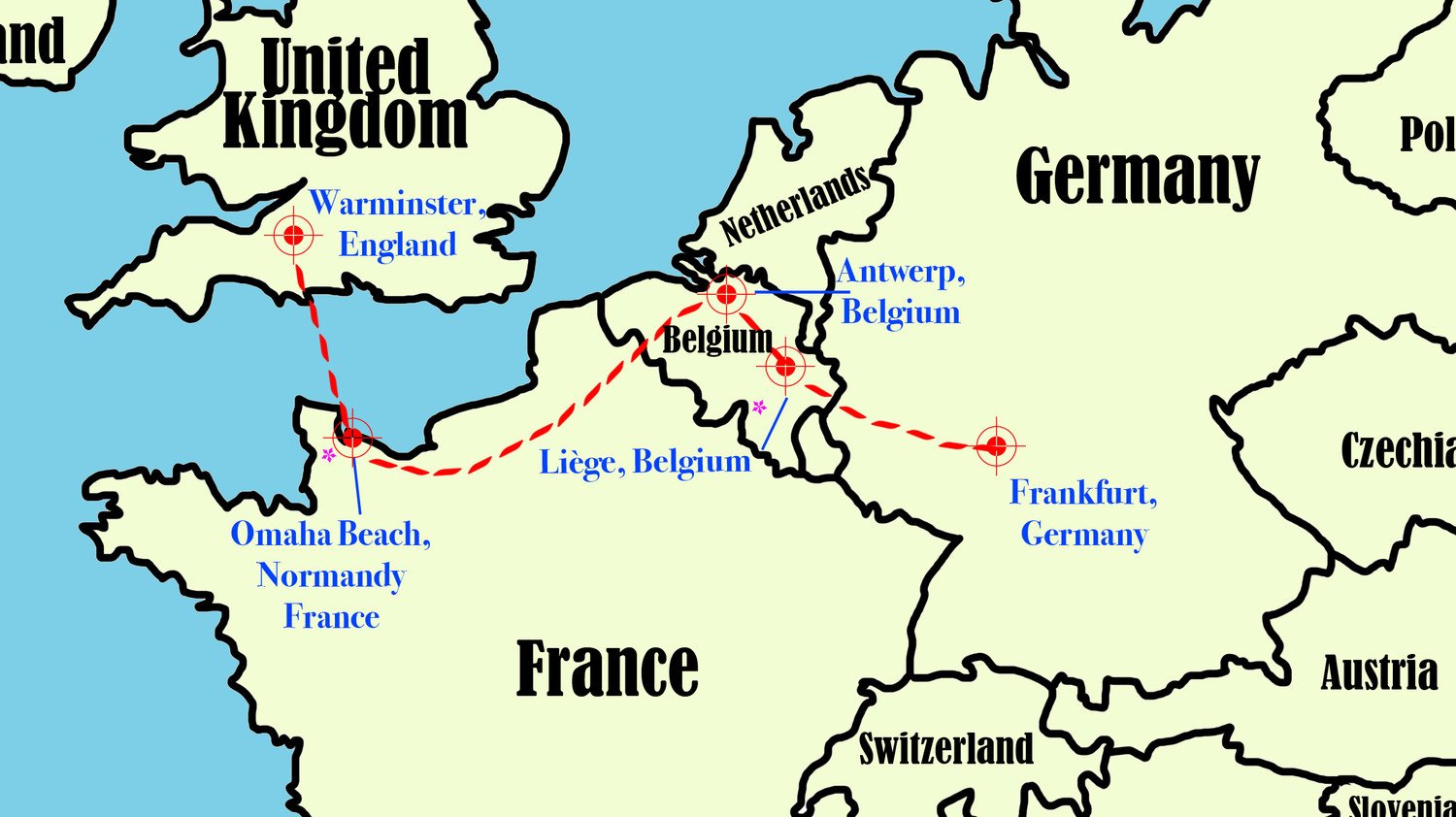

Sitting in the warmly lit living room of his Oceanside home of 63 years, Seitman recounted his four-year journey across the continent: from Le Mans, France, to Antwerp and Liège, in Belgium, and, finally, Frankfurt, Germany. At each post he relayed calls from London and Washington to the generals and commanders coordinating the war effort in Europe. He met Generals Dwight Eisenhower, George Patton and Omar Bradley. “Nice guys” he said.

He agreed to speak of his wartime experience — much of it for the first time — for Veterans Day. When this reporter arrived, Seitman, 95, quickly slurped his coffee before loudly setting the cup down and shuffling a few feet from the kitchen to a chair in front of the wall of souvenirs that he and his wife, Shirley, collected during their post-war travels around the world.

“It’s wonderful that this history is being renewed at this time,” Shirley, 90, said of the urgency of recording her husband’s experience during the war. They never spoke of it, she said, until recently.

“It’s important that the young people know what happened,” she said. “Much of it has already been buried.” Roughly half a million American World War II veterans remain alive in 2017, according to the National World War II Museum.

The two Brooklyn natives met in 1949 on a Labor Day bus trip to the Poconos organized by a Manhattan-based Jewish youth group. Seitman was there by chance. A friend of his had backed out of the trip and asked him if he would take his ticket.

He noticed Shirley immediately, he recalled, and he scribbled her phone number on the back of his ticket receipt after overhearing her give it to an operator. Coincidentally, her father, Michael Suttenberg, had been Seitman’s chemistry teacher (and a well-known jokester) at Samuel J. Tilden High School in Brooklyn.

Seitman asked if she was related. “I pretended not to know who he was,” Shirley said of her father, until she was sure Seitman had a positive opinion of him. She owned up to the truth when he mentioned how funny his classmates thought Suttenberg was. The two married in June, 1950.

Seitman received a degree in accounting that same year from the City College of New York and became a certified public accountant — his career until he retired in 2012.

The couple were and remain avid travelers, and estimate that they’ve visited 150 countries. This winter, they plan to take a cruise and bring that number up to 152. Their Perry Avenue home is crowded with the hundreds of souvenirs they have collected over the years.

They attempted to trace Seitman’s wartime journey across Europe, during which he and his unit trailed behind Patton’s Army, waiting for the general to punch through the German lines before setting up command posts and direct lines to the White House, London, the Pentagon and other command locations. On the side, Seitman periodically made calls to Pacific Navy command to keep tabs on his brother Murray, who was serving aboard a troop transport.

By the time Seitman reached Frankfurt, the war was coming to a close. He heard of Germany’s surrender from a group of Polish refugees fleeing the Soviets. “They knew what was going on,” he said. “We didn’t.”

“Hallelujah,” Seitman recalled thinking upon hearing the news, and his unit readied to deploy to the Pacific.

“I didn’t want to go,” he recounted, but shortly before shipping out, the same group of Polish refugees informed him that the Japanese had surrendered as well. The atom bombs ended the war, he said “boom, boom.”

Seitman doesn’t remember the port he shipped out from, but he does recall arriving in New York City in 1946 aboard a hospital ship he had been attached to for Operation Magic Carpet, the mass exodus of the roughly 7.6 million American service members who served abroad during the war.

Much of that chapter in Seitman’s life remained closed until today. “They were dark days,” Shirley said. “ …We never discussed it.”

“There was nothing to talk about,” her husband shot back.

Most of the men she dated after the war before Seitman, she said, “just wanted to get back into the swing of things,” and few ever discussed their experiences.

The two made new memories in their 67 years of marriage. Besides their travels, they had two children — both Ocean side High School graduates — three grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

“We’ve seen the world,” Shirley said. “We’ve had a good life.”

49.0°,

Fair

49.0°,

Fair