Lawyers, Muslims and activists disavow Trump’s immigration ban

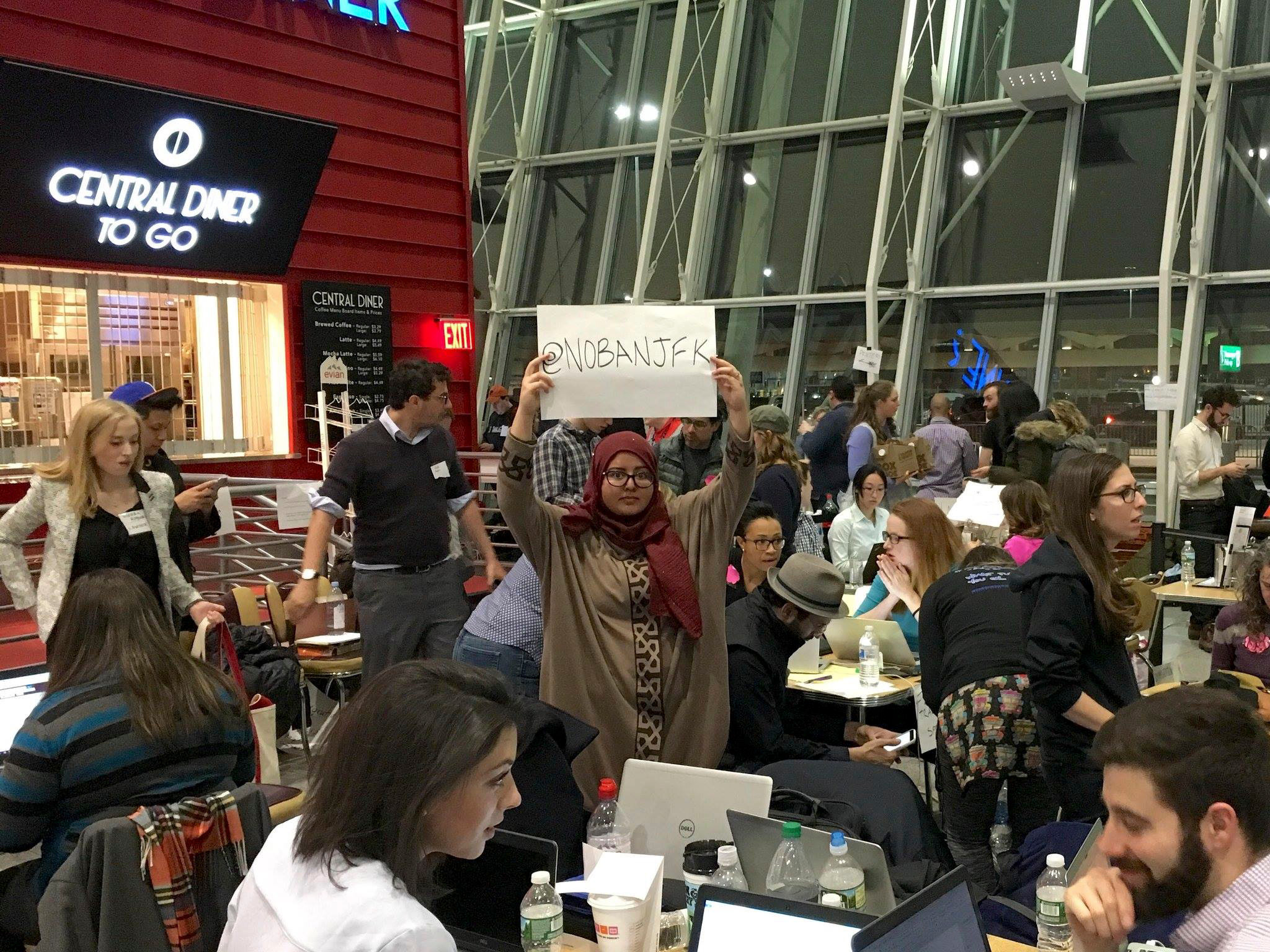

In a matter of hours after President Donald Trump’s executive order limiting immigration on Jan. 27, several terminals at Kennedy Airport were transformed into makeshift independent law firms tasked with freeing detained legal immigrants who were denied entry into the U.S.

Mehreen Hayat, a civil litigator — and a graduate of Central High School in Valley Stream — was informed of the effort through her membership in Lawyers for Good Government, an advocacy group of more than 120,000 lawyers, law students and activists that formed after Election Day to defend American values.

Hayat arrived at the airport on Sunday afternoon, by which point the waiting area at Terminal 4 already had a network of computers and printers, a schedule of volunteer shifts and a database of applicable legalese to expedite the process of getting would-be clients in front of a judge. To her surprise, there was even a nine-page volunteer handbook circulating among the group.

“… As needs arose, people were saying, ‘We need this,’ and people would show up with printers,” she said.

Hayat, who lives in Franklin Square, is a member of the Muslim Bar Association of New York. She said she knew of about 600 lawyer volunteers who were operating at JFK in the days after Trump’s order, which barred citizens of seven Muslim-majority countries — Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen — from entering the U.S. for 90 days, and suspended the U.S.’s refugee system for 120 days.

A federal judge in Brooklyn issued an order blocking part of the president’s action on Saturday. Then, on Monday night, Trump fired Sally Yates, the acting U.S. attorney general, after she refused to defend the executive order, and replaced her with Dana Boente, the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, who said he would enforce the ban.

In the mass confusion at Kennedy and other U.S. airports, a number of foreign travelers who were attempting to enter the country this weekend — many of whom were green card holders or had valid immigration visas — became detainees.

“I understand people who are against illegal immigration,” Hayat said. “At least I can understand where you’re coming from. But these are all legal immigrations. These are people who have been vetted. They all have ties to this country. They’re not trying to scam anybody — they’re not crossing the water or digging holes. They went through the proper channels.”

The process of finding people to help, Hayat said, was straightforward. Volunteers monitored family members who were waiting at arrival terminals for long periods of time, and approached them to see if they needed legal assistance.

Attorneys also tried to contact people who had already been deported, or who were stopped at airport security in foreign countries. Hayat said that they were coordinating the deployment of translators as well, as language barriers arose.

“So far, stays and temporary restraining orders are not saying the executive order is unconstitutional,” she explained. “But they’re saying that there’s enough evidence that it might be found unconstitutional that we shouldn’t be enforcing it yet.”

Peaceful demonstrations across the country

“I’m not really much of a protest guy,” said Karim Mozawalla, 40, a trustee at Masjid Hamza Islamic Center of South Shore in Valley Stream.

Mozawalla was recovering from a stomach virus on Saturday when he and his daughters decided to go to Kennedy Airport to show their support for the Muslim community. “The mood was very uplifting,” he said. “It was inspiring to see so many people in support of this.”

Photos of his daughters passing out pizza to demonstrators circulated on social media over the weekend, which earned them the nickname “Pizza Angels.”

“I feel that this ban ignores humanity for a false sense of security,” Mozawalla said. He added that the mosque was planning to hold seminars to offer its congregants basic legal advice pertaining to the ban. He said the mosque was accustomed to receiving rude phone calls, with callers saying things like, “You’re not welcome here,” but he didn’t think the frequency of those calls had increased lately.

Ali Waheed, 27, a 2016 graduate of Hofstra Law School, was also unaccustomed to going to protests, but felt compelled to go. “I couldn’t stay at home and watch it,” he said. “It was kind of like my civic duty. As a Muslim and someone who was born in Pakistan.” Waheed said that he and his family travel back and forth between his home country and the U.S., but he wasn’t sure they would continue to.

He has friends from high school, he said, who are staunch Trump supporters and who have praised his anti-Muslim campaign rhetoric on social media — perhaps not realizing that Waheed is Muslim, and sees those comments, too. “I guess you’re forgetting that you used to come to my house and we used to go over each other’s house?” he said.

Waheed said he would continue to protest the ban at JFK, and encouraged detractors of the order not to be afraid to speak out against it. “If you’re still on the fence, or you’re just watching from the stands, it’s really important to be proactive in your beliefs,” he said. “Because, you know, it only takes one person to make 10 or 20 other people interested in participating in a protest.”