In local schools, learning isn't just a habit

New ways of thinking at Seaford Manor

What is “metacognition”? How can students become better at managing their own learning?

The student body of Seaford Manor Elementary School assembled in two shifts on a crisp, sunny morning last week to ponder these and other questions not traditionally part of an elementary school student’s day.

“We want to help our students become more efficient and efficacious learners,” district Superintendent Dr. Adele Pecora said. To that end, this year the district is introducing the 16 Habits of Mind, a set of values enumerated by curriculum consultants Arthur Costa and Bena Kallick that includes such traits as persistence, empathy, managing impulsivity and thinking flexibly.

The children in kindergarten through fifth grade not only pondered the habits; they gave clear, well-reasoned explanations of them, along with examples from their own experience. The students’ grasp of the concepts was all the more impressive considering that they had only been working on the 16 Habits since September.

Dr. Marc Ferris, the Wantagh School District’s assistant superintendent for instruction, said that his district is working with a streamlined version of the habits. “I’m familiar with them, and we looked at them,” he said. “We felt 16 might be too many for elementary school students to really internalize.” Ferris and district Superintendent John McNamara asked teachers to list the habits they felt were most important and settled on persistence, managing impulsivity and working collaboratively.

Wantagh’s approach has included developing rubrics by which behaviors can be assessed and graded. “If we don’t give them a grade on something, they start to think it isn’t important,” Ferris said. “And we ask them to set goals for themselves and then grade themselves and each other.”

Seaford students appeared to grasp the concepts readily. Fourth-grader Carrie Cassarello said, explained the habit of thinking flexibly, sayign “If I’m doing something that doesn’t work, I try it another way,” Sabrina Loffredo explained managing impulsivity simply as “thinking before I act.” Classmates offered examples from their experience on all 16 habits, with older students helped younger ones.

The assembly was part of an initiative begun two years ago under Pecora’s leadership called Growing Your Mindset, enthusiastically implemented at Seaford Manor by a team led by Principal Deborah Emmerich. “The future belongs to a vastly different kind of student with a vastly different kind of mind” than the students of 20 or 30 years ago, Pecora said, adding that those minds would need different skills as well.

“I’ve known Bena for about 20 years,” Pecora said of Kallick. Pecora began implementing the 16 habits while still working as a history teacher in Massapequa. When she moved into the administrative offices in a series of increasingly responsible positions, she took the tools with her, she said. She is now in her second year as superintendent, and colleagues agreed that she is almost ideally positioned to guide the process.

The school has monthly assemblies like the one last week, Emmerich said. Teachers also have workshops, so they can become more familiar with the habits themselves. Students all learn the information using the same language. “They all talk about the habits in the same way,” Assistant Principal Mary-Ellen Kakalos said. “This allows students to talk about the habits in and out of the classroom using this shared vocabulary in a way that avoids confusion.”

Both Pecora and Seaford Middle School Principal Lisa Dunn were on hand for the assemblies and breakout sessions afterward. The habits, introduced at the elementary level, will continue to be taught as students move through middle and high school, ultimately forming part of the entire district’s curriculum, according to John Striffolino, assistant superintendent for personnel, instruction and curriculum.

“These are not new ideas,” Pecora stressed. “They’ve been around for a very long time.” What is new is their inclusion in a curriculum that seeks to educate the whole person.

“It’s not a flavor of the month,” Striffolino stressed. “You’d be hard pressed to find a school district that isn’t doing something similar.”

Parents are key to the program’s success, Seaford Manor social worker Jennifer DiMieri said. “Students take this home and explain it to their parents,” she said. “Then they interview their parents. They ask their parents for examples of these habits out of their lives.”

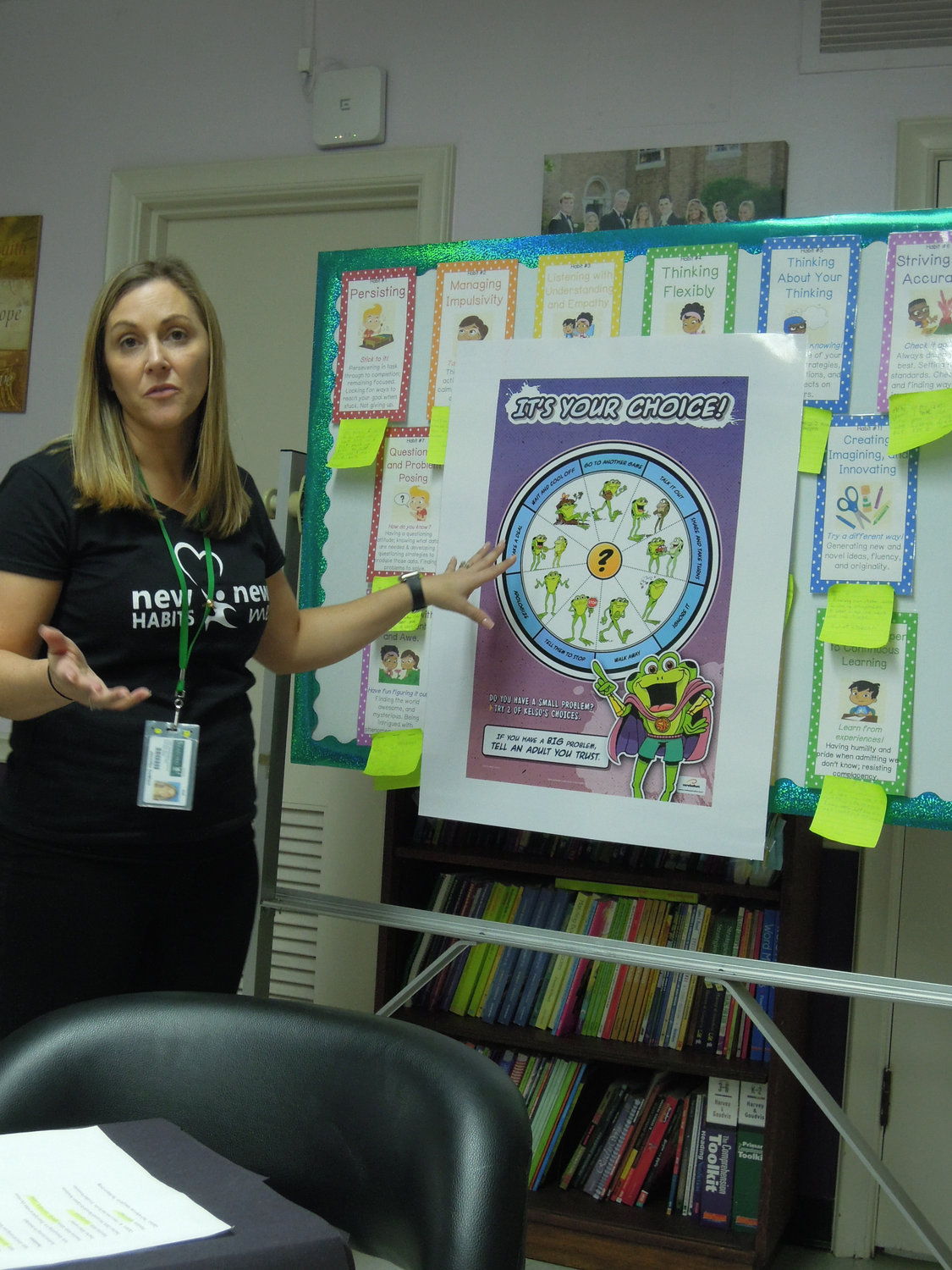

Students are also encouraged to use other tools throughout the school day, such as Kelso’s Choice, a technique for dealing with bullying and other forms of conflict. Kelso is a frog, and his choices comprise nine possibilities for solving low-key problems that arise throughout the school day.

For larger issues, students are always encouraged to speak with an adult. But Kelso’s Choice helps students to become empowered by seeking their own solutions to smaller problems, DiMieri said.

Academically, the 16 habits help students see patterns in both positive and negative situations. “It’s not just character education,” Pecora said. “If students are having difficulty in math, they have the tools to see patterns, to see where the difficulty is. And because of habits like persisting or flexibility, they don’t just give up and say it’s too hard. They can look for another solution.” Math might seem like an obvious area for the application of the habits, Pecora added, but she found them equally helpful in her history classrooms.

The habits are reinforced throughout the school, with posters in every classroom, and a large bulletin board is planned where students can post their own stories detailing their experiences using the habits.

At Seaford Manor, older students share what they’ve learned with younger students. In the morning’s second assembly, fifth-graders helped third-graders understand the meaning of empathy by describing a number of scenarios and exploring possible responses. They made boxes with pictures of shoes on the sides so the younger students could almost literally stand in someone else’s shoes while discussing options.

“It’s great to see the kids’ eyes light up when they see the impact they can have on other students,” Emmerich said.

“Remember,” added Kakalos, ‘It takes a village.’”