‘Our shelves keep going bare’

Hanse Avenue food pantry struggles to feed needy families

By REINE BETHANY

rbethany@liherald.com

People praise the work of food pantries and the role they play in the community. However, it’s critical to recognize that when they’re in trouble, everyone is in trouble.

According to Yolanda Murphy and Anthony Achong, of the Long Island Council of Churches in Freeport, pantries need all of us to step up.

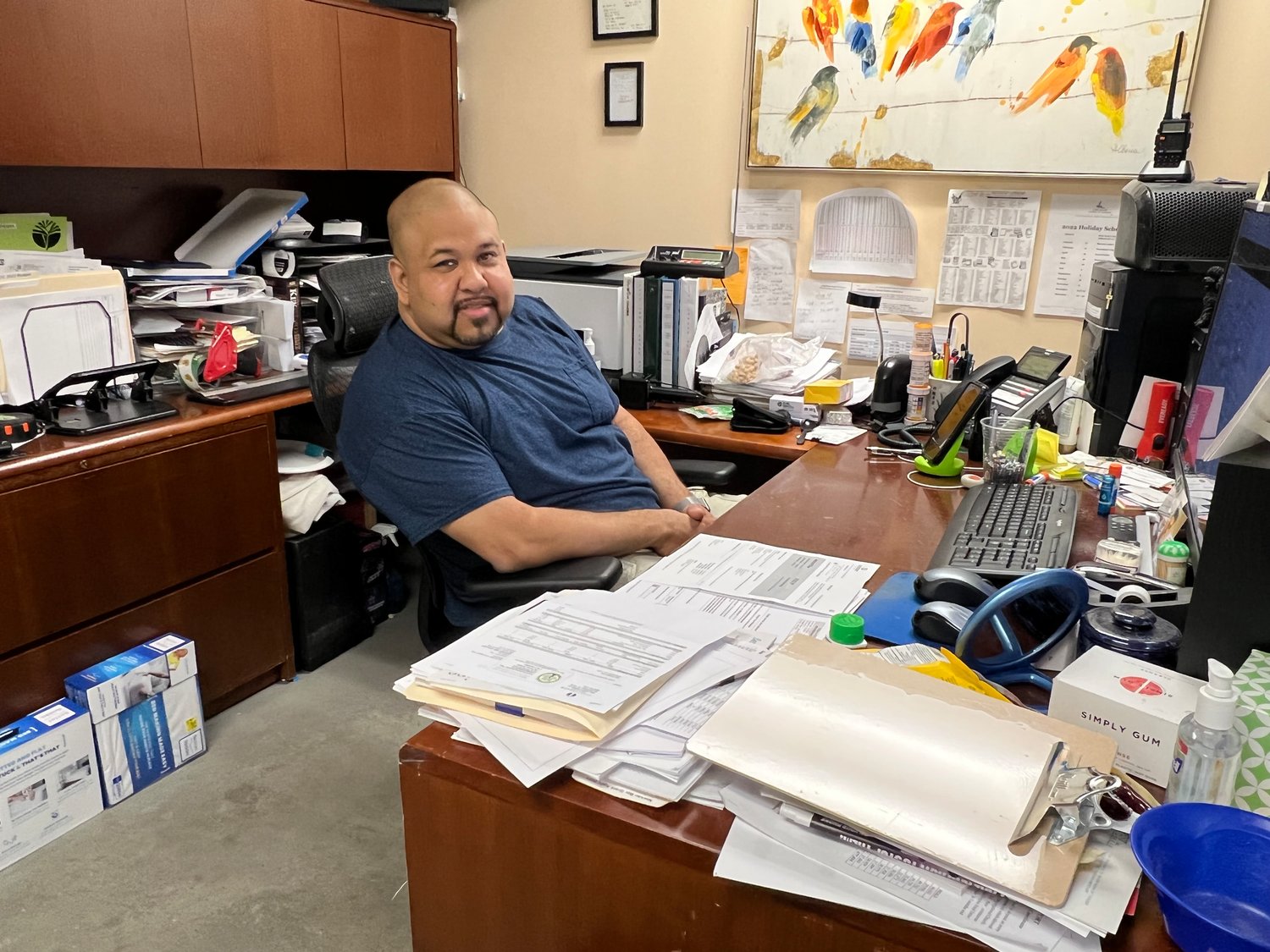

Murphy, 61, is the managing director of the LICC. Achong, 47, is director of administration and operations. From their administrative office and warehouse at 230 Hanse Ave., they stabilize the diets of more than 50,000 people annually.

Twice a month, families and individuals may come to the warehouse, fill out a form and receive a shopping cart packed with cereal, milk, canned goods, fresh produce, and fish or meat. Specific requests for items like bathroom tissue, diapers, baby formula, toiletries, or pet food will also be honored — but only if donations keep the shelves filled.

“We’ve just run out of the food from the People’s Food Drive,” Murphy said, “so our shelves keep going bare very quickly and donations are trickling in very slowly. We won’t get government funding for at least eight more weeks.”

The 11th Annual People’s Food Drive, run by Rob and Mary Hallam of Malverne, unloaded several box trucks of food into the LICC warehouse March 19. As those items have vanished into needy homes, the facility is looking toward funding from the American Rescue Plan Act via United Way, in the amount of $50,000.

“Ironically,” said Achong, “that’s about what we’ve spent already this year. We’ve actually tapped into our reserves, and we have about $5,000 left — for the rest of the year.”

Achong and Murphy have seen donations drop before in response to circumstances like those they are seeing now.

“People feel unable to give donations like they usually give because of food and gas prices rising,” said Murphy.

“We’re also seeing shortages from our board donors, Long Island Cares, Island Harvest,” said Achong, “because they’re getting less. Where we were getting thirty pallets a month from them, we’re down to six or seven or eight.”

Meanwhile, the pantry is getting more requests now than a few months ago. A significant number come from families who had managed to make ends meet until recently.

“We’ve got a whole window of people that we weren’t seeing before,” Murphy explained. “Even if they’re not below the poverty line, some of their mortgages have gone up, then they’ve got the food inflation, the gas inflation. If one person loses a job out of a household, they’re feeling the pinch.”

At her office computer, Murphy brought up the statistics that support her words. The numbers come from the forms that each applicant for a shopping cart must complete upon arrival at the pantry. Murphy inputs the numbers to a spreadsheet.

Choosing a spreadsheet from a date in late April, Murphy read out, “So, this particular day, 65 households, 104 children, 157 adults, 19 seniors. So by the time we add these all up, we served almost 5,000 people last month—2,773 adults, 324 seniors, 313 new clients, only 2 veterans, 1,218 households.”

The combined uptick of new recipients with the downturn of donations has forced LICC to tighten its giving policy. “When the pandemic hit, they could come four times a month,” Achong said. “Now we’ve had to tell them, only twice a month. If it gets worse, then they’re only going to be able to come once a month.”

Another category of recipient is the undocumented.

“They don’t have access to the resources of a citizen,” Achong said.

“And not only that,” Murphy added, “those are the people that used to get work from Home Depot, or off the books work, but now citizens who lost their jobs in the pandemic are taking those spaces,” leaving undocumented workers without the employment stream they once had.

The donors from partner churches are still coming, like Marilyn and Tommy Rodahan, who bring bags of nonperishables from the United Presbyterian Church in Levittown. Thomas Hodge comes too, from the United Church of Christ in Rockville Centre.

“Once a month, during Communion Sunday, we collect food,” Hodge said. Another man named Tom in his church always gives diapers and baby formula. In addition, Hodge and his wife periodically run a collection through the United Christian Church Nursery School, which they founded 52 years ago. “We want the children to learn about giving,” Hodge said.

Food insecurity is more than a matter of compassion. It also affects community health.

“When people can’t get good food, it weakens their immune systems,” said Murphy. “They’re catching the colds, they’re catching the flus, they’re getting iron deficiency,” especially if they have to fill up on food low on nutrition, but high in cholesterol and carbohydrates.

“Another concern for us is that people might be eating food or meat that’s out of date because they don’t have a choice,” said Achong.

“So they’ll get sick because it’s either this or nothing.”

A sicker populace, of course, puts pressure on the community’s medical facilities, causes lost work days, and lowers the community’s wealth.

Making sure the food gets handed out motivates the volunteers who come to pack the shopping carts. As one volunteer said, “I just want to help the community.”

47.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

47.0°,

Mostly Cloudy