Mount Sinai South Nassau places one last steel beam

New patient pavilion includes 40 beds for critical care

It’s a tradition dating back to some of the earliest days of modern construction. When a building is almost completed, the builders celebrate its construction by placing the last steel beam at the highest point in what’s known as a “topping out” ceremony.

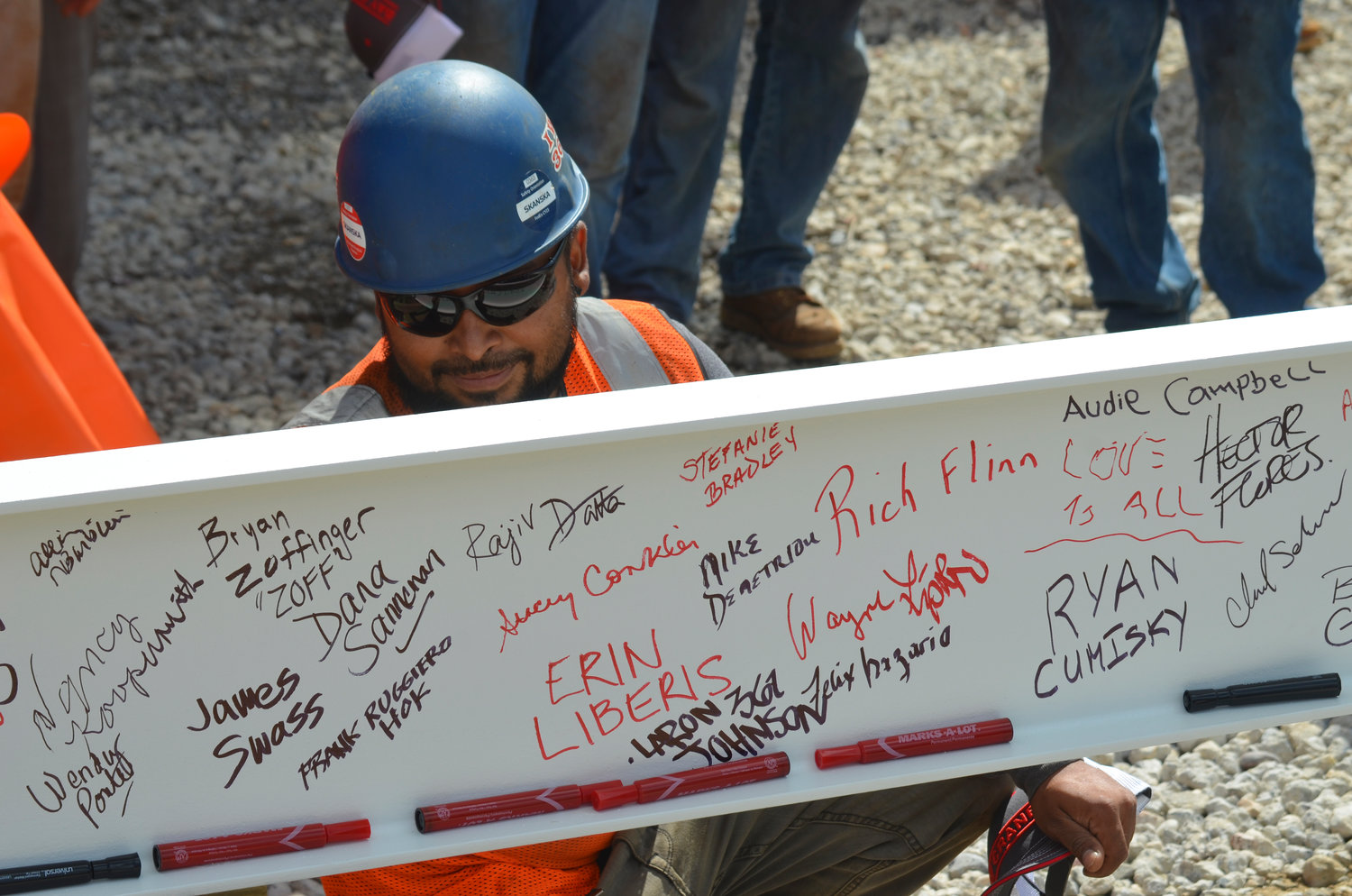

Mount Sinai South Nassau upheld this custom with its own topping out ceremony last week, celebrating the completion of the four-story J Wing Patient Pavilion at Oceanside’s One Healthy Way. More than 40 people — including board members, construction workers and other staff members — gathered for photos with the final steel beam of the building’s construction.

Attendees — clad with white hard hats — signed their names onto the beam, and cheered when it was hooked to a crane and hoisted up to the top of the building, where it was placed securely.

The steel beam was adorned with an American flag on one end, a small tree on the other, and a large Mount Sinai banner draped in the middle. Damian Becker, Mount Sinai South Nassau’s public relations manager, said the tree represents the fact there were no injuries or accidents on the job site, and traditionally, is supposed to stay in place.

The beam was placed up past the fourth floor and toward the back, said Mark Brundage, a sales and operations worker for JC Steel, who created the beam. Even so, its tree was still visible from Nassau Road.

The patient pavilion will feature an extended emergency department, add 40 new beds for critical care patients, and nine modern surgical suites under one roof. Joe Calderone, a spokesman for Mount Sinai, said the operating rooms would be large enough to potentially provide open-heart surgery and other cardiac services — if approved.

“Currently we need a certificate of need from the New York State Department of Health,” Calderone said. “But providing open-heart surgery to our patients is the goal.”

Mount Sinai’s operating rooms are fully functional and viable facilities, the spokesman added, but open-heart surgery and other cardiac procedures require larger rooms to accommodate all necessary equipment — which the new patient pavilion will provide. Standard operating rooms of this scale require 250 square feet, but the J Wing Pavilion will provide operating rooms of up to 600 square feet.

The patient pavilion’s construction is part of a Federal Emergency Management Agency project as a result of the flooding and damage that occurred at the Long Beach Medical Center following Hurricane Sandy. In all, FEMA is providing $113 million to the project — part of an overall $158 million in funding that also includes the Long Beach Medical Center.

“We used some of the FEMA money in the Long Beach Medical Center, and some of it here to strengthen our campus,” Calderone said.

Joseph Fennessy, immediate past chair of Mount Sinai South Nassau’s board of directors, says the medical group needed to consider where the health care industry was going. A lot of what hospitals traditionally provided was becoming part of services now taking place in the offices of physicians and ambulatory surgery centers.

“The challenge for us as board members was to figure out how we’d be relevant in the new world of health care,” Fennessy said. “We realized we need to be an institution that performs more tertiary-type work — like open-heart surgery — things that are more complex, to meet the needs of South Shore residents.”

Dr. Adhi Sharma, president Mount Sinai South Nassau, said planning for the J Wing Patient Pavilion began in 2018 after learning neighbors in and around Oceanside were seeking cardiac procedures over the river in Manhattan.

“When we partnered with Mount Sinai in 2018, we shared our goal to grow our cardiac program at this hospital,” Sharma said. “In supporting that goal, they’ve worked with us toward expanding cardiac services at the hospital including — open-heart surgery, expanded structural heart programs and electrophysiology.”

This building would make Mount Sinai the only hospital on the South Shore to offer cardiac services, Sharma added, assuming it’s approved by the health department. The pavilion would also be a boon for the hospital if another global pandemic were to occur in the future.

The hospital has learned many new techniques to optimize exposure and infection prevention within the hospital following the pandemic, Sharma said. For example, all emergency treatment areas are now built as single rooms with hard walls — instead of curtains — to prevent the spread of disease. The air filtration system is designed such that each patient has clean air coming in from the outside in their rooms, while hospital air is filtered out.

The pandemic did slow the pavilion’s construction, however, thanks to both illness and supply chain issues. What was supposed to have been opened by now is now expected to start serving South Shore patients in 2024.

47.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

47.0°,

Mostly Cloudy