Anti-Racism Project sparking dialogue among neighbors in Rockville Centre

“The more I hear, the more I realize I have a lot of personal work to do on myself,” Rockville Centre resident Bill Kurrus said after the second session of the Anti-Racism Project on Oct. 17. “It’s raised my consciousness.”

Over the past year, local leaders from Raising Voices, the Hispanic Brotherhood of Rockville Centre, Central Synagogue-Beth Emeth, the United Church of Rockville Centre, the Sisterhood of CSBE and the village’s Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Center met to develop a curriculum for the Anti-Racism Project, which has about 30 participants. The eight-week program began on Oct. 9 and is already meeting its goal of sparking dialogue among neighbors.

There have already been some uncomfortable conversations and the “opening of wounds,” according to participant Richard Geffen, of Rockville Centre. “It’s just an opportunity to actually talk about this,” Geffen, 62, said after the session. “People talk about it, but on the surface. We’re really delving into it.”

Kurrus, 67, added, “We all have prejudices in us. As adults, I think the hope is to bring it to the surface, be conscious of it and go from there.”

The evening’s topics included whether Jewish people are considered to be a separate race; a back-and-forth about whether racism is as much of a problem globally as it is in the United States; how the media differently portrays white and black people charged with or convicted of crimes; and open discussion on specific stereotypes that people associate with various races.

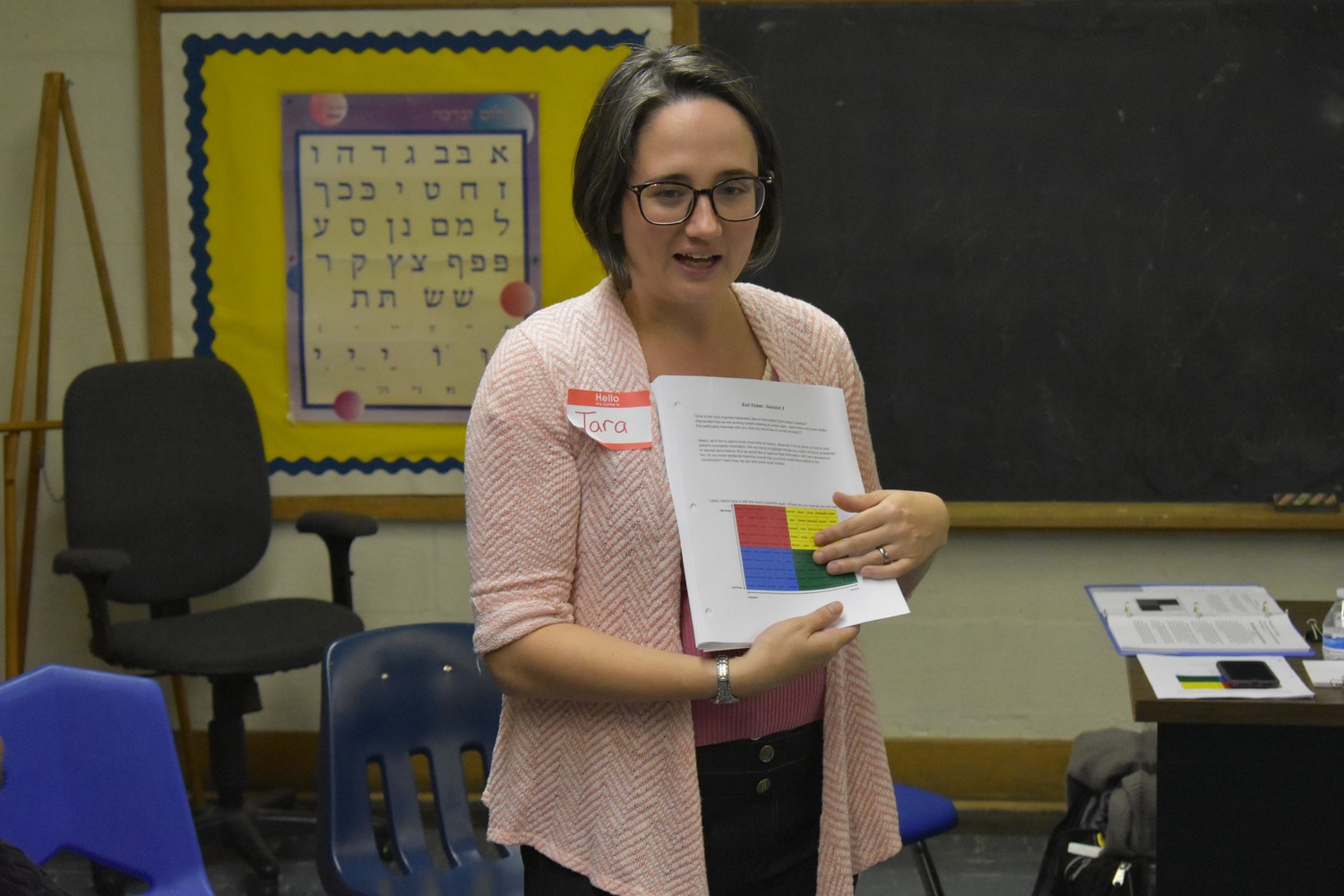

But the second of eight lessons, held at Central Synagogue-Beth Emeth, focused primarily on the history of racial injustice, and attendees were first asked to share their feelings about discussing the past examples of discrimination. Some may be excited, facilitator Tara Brancato told the class of about 10 people. “Maybe you feel apprehensive,” she added, “because you don’t know what you don’t know.”

Brancato, a teacher at a public school in Queens, recently moved to Lakeview and joined the Unity and Diversity Committee of Raising Voices, a local advocacy and civic engagement group that formed shortly after President Trump was elected. Rena Riback, co-chairwoman of the committee, helped bring the idea of the Anti-Racism Project to fruition after an unknown person drew a swastika on one tree and the N-word on another tree in white paint in front of a Brower Avenue home near Capitolian Boulevard last year.

With experience in teaching social studies — including courses on the Holocaust and human rights — Brancato helped develop curriculum for the Anti-Racism Project and then was asked to facilitate the sessions. She led the session with Lois Cooper, an author and diversity and inclusion consultant, and Carol Fisher, a social worker.

Brancato noted that though Lakeview is a diverse place, it often feels segregated. “My personal goal was to sit down with community members and see if we could change that and talk about problems of privilege and oppression in our own community,” she said.

Jenn Coghlan, 42, of Rockville Centre, said she took the class because its curriculum is not always available to the average person. Though she knew some of the instances of racism in American history, she learned more examples. “I think you can’t really address a problem if you don’t have any background of how it came to being in the first place,” she said.

Cooper handed out cards with information about various racist moments in American history, and the class members read them one by one.

One participant read the first definition of “white” in 18th century Virginia, which was used to determine which people had more power in the colony. Defined as having Caucasian blood — and “not one trace of Negro or Indian blood” — the definition was changed to accommodate the descendents of John Rolfe, a prominent tobacco planter and landowner who married Pocahontas. Bernice Sims, of Mineola, laughed and shook her head in disgust. “He got a mulligan,” she said.

Though some discussed the idea of unconscious bias, Cooper said she does not believe that exists, noting the long history of racism. “It’s bias,” she said. “We’ve learned it.”

Others read cards about the Three-Fifths Compromise in 1787; the emergence of the Ku Klux Klan in Pulaski, Tenn., in 1866; the Supreme Court decision in 1944 that upheld the right to relocate and detain people of Japanese ancestry in war relocation centers; and Vincent Chin being beaten to death in Detroit in 1982 by two white auto workers with baseball bats who blamed the Japanese for the loss of their jobs, among others. Chin was actually Chinese-American. Judge Charles Kaufman sentenced the killers, Ronald Ebens and Michael Nitz, to three years of probation and a $3,000 fine, saying, “These aren’t the kind of men you send to jail.”

The room was silent, until Kurrus asked, “Are we going to do some pick-me-up stuff?” Later, he inquired again, after discussing several readings, “Are we going to end this on a hopeful note?”

“You’re the hope, Bill,” Cooper said, noting that participants can take what they learn and make a difference. Brancato told the Herald that the Tuesday and Wednesday classes will combine for two sessions in several weeks to “cross-talk and compare notes,” as well as formulate plans to take action locally.

“We’re hoping that other people will be inspired to take their own projects forward,” Brancato said.

Outside of just race, Coghlan said the discussions have helped her avoid making assumptions when she encounters people she does not know well. “Learning to check that instinct,” she said, “and find out who people are before you fill in all the blanks for them I think is really important.”