Friday, April 19, 2024

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

44.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

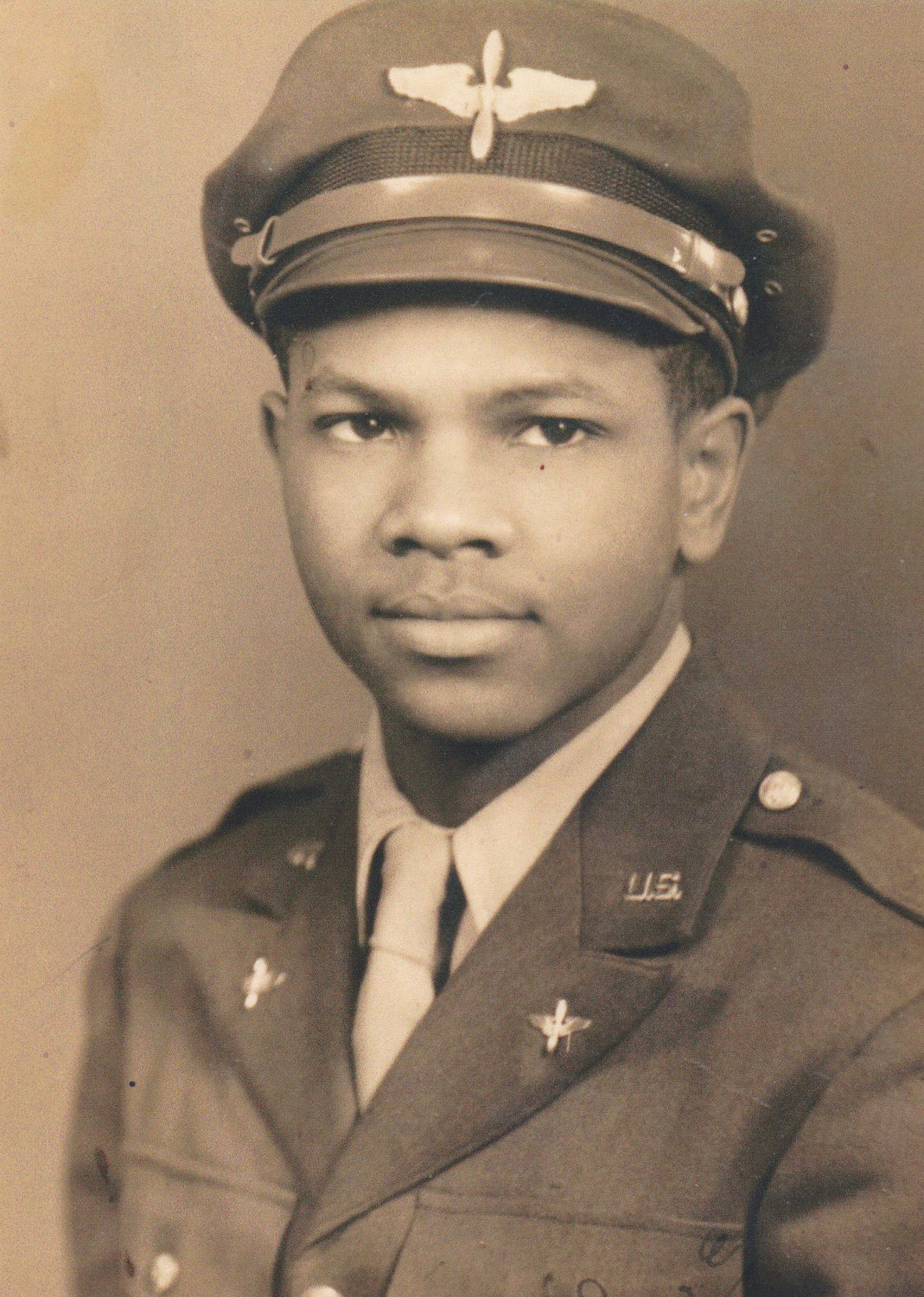

Joe Johnson, Glen Cover and Tuskegee Airman, dies at 95

William Joe Johnson has a special place in the annals of Glen Cove: He will go down in American history as a member of the Tuskegee Airmen, a group of Black fighter pilots who served in the U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II. Formed in 1941, the regiment was the first of its kind, because Black men had never been permitted to fly military planes.

Over the past 70 years, Johnson could be found all over Glen Cove, spending time with his family at Morgan Park, sharing his experiences with neighborhood children at the local Boys & Girls Club and at schools, or simply sitting on his front porch, enjoying his immaculately groomed garden.

Johnson died on Jan. 28, at age 95. His wife, Teresita Medina-Johnson, said the cause was acute kidney disease.

Born in North Carolina on Sept. 29, 1925, Johnson was the fourth of Lilly and Ellis Johnson’s nine children. His family moved north when he was 4 to escape racism in the south, settling in Glen Cove in 1929. Aside from his time in the military, Johnson lived in the city for nearly 90 years, attending Glen Cove High School before his service and settling down in the city afterward.

In a 2019 interview with the Herald, Johnson said he knew he wanted to fly from an early age — and he also knew that none of the planes he saw overhead were flown by Black men, which was something he sought to change.

He graduated from high school in 1943, and was drafted soon after. He joined the Tuskegee Airmen as a cadet and began training as a pilot.

As much as Johnson enjoyed flying, he would never forget the racism he experienced in training. He trained in Nebraska, Colorado, Mississippi and Alabama, and racism was everywhere, inside and outside the Army bases. The armed forces were not integrated until 1948, so Johnson and his fellow airmen lived in separate barracks and rode in separate train cars. White soldiers did not even salute their Black counterparts.

Tony Jimenez, Glen Cove’s veterans affairs director, said that the Tuskegee Airmen served a vital role in American history. Their service record was excellent despite low expectations: They never lost a single airship in their escort missions.

The subsequent integration of the military was due in large part to the performance of the Airmen, Jimenez said. “It sets an example of if you persevere, if you try hard, if you really push, you can go anywhere,” he said. “[Johnson] used that as an example for kids to get motivated and do their best.”

After he left the service, Johnson attended several colleges while deciding what he wanted to do for a living. He worked in construction at first before joining Grumman Aerospace, where he eventually became a supervisor.

He also attended functions at the Lincoln House, where Black Glen Covers often met for a variety of events. There he met Elise Willis, and they married in 1948. They had three children — Michele, in 1953, Terry, in 1954 and William Ronald, in 1955 — and six grandchildren.

Terry, now Terry Finney, said that Joe was a great father, strict but fair, who offered his family constant love and encouragement. He frequently took them to museums, to upstate orchards to pick apples and to the 1964 World’s Fair in Queens. Education was paramount to her father, Finney said. He wanted everyone around him, regardless of race, gender, creed or financial status, to have a shot at succeeding.

No matter where he went, Finney said, being a Tuskegee Airman was always important to him. “It made him proud,” she said. “It made him know that African-Americans, despite the hardships they went through, made it and proved that they can do the same thing that everyone else could do so long as they tried and applied themselves.”

Elise died of a heart attack in 1989, and Johnson spent the next decade living on his own. That changed, however, when he met Teresita Medina in the early 2000s. They married in 2002. Although Medina-Johnson, 53, said it took a while for her to warm up to him when they started dating, she soon realized how loving Johnson was. She said she would miss his presence, his love of storytelling and his care and affection for her.

Glen Cover Fred Nielsen, a Marine Corps veteran and the Herald’s 2020 Person of the Year, said that Johnson was a conduit to Black history and Black pride. One of Nielsen’s favorite memories of Johnson was when he was honored at a 2016 gala hosted by Heroes Among Us, an organization dedicated to helping veterans. Nielsen presented Johnson with a Boy Scout knot board, and when he came up to receive it, he asked to speak, surprising Nielsen aback.

Johnson leaned on his cane, and then sat down and told the crowd of 350 people about his life, in which he had seen so much that was painful for the Black community. His story enthralled the audience, Niel-sen said. “There was no bitterness, there was no anger, in spite of what he had seen and experienced,” Nielsen said. “Everyone just attended him.”

Virginia Cervasio, the founder of Heroes Among Us, said Johnson was as humble as they come. He did not consider himself a hero, and was instead just proud to have served his country as an Airman.

“What they had to go through to get to even serve in that capacity for our country — they had to bear it all,” Cervasio said, “but they stayed with it, and they fought against it, and they made sure to serve our country in the best way they could.”

Nielsen recalled asking Johnson sometime later how he couldn’t be angry given all he had experienced. Johnson gave Nielsen a half smile and said that in his lifetime, he had known many Black men and women who were raised by slaves and their descendants. As he grew up, however, he saw more and more Black people take on roles in American society that he never thought possible, culminating in the inauguration of President Barack Obama.

“People will miss him for the dignity of his thought and the dignity of his living,” Nielsen said of Johnson. “He didn’t seek to be an example for anyone, but his life, as he lived it, his words, as he shared them, were certainly inspirational.”

Toward the end of his life, Johnson was approached by hobby pilots who learned about him and the Tuskegee Airmen. They invited him to fly a plane on the same route from Mitchel Air Force Base, in Garden City, over his Glen Cove neighborhood, that he had watched countless planes fly as a child.

Johnson accepted, and had the chance to fly one last time, soaring over the spot where he once thought it would never be possible.

HELP SUPPORT LOCAL JOURNALISM

The worldwide pandemic has threatened many of the businesses you rely on every day, but don’t let it take away your source for local news. Now more than ever, we need your help to ensure nothing but the best in hyperlocal community journalism comes straight to you. Consider supporting the Herald with a small donation. It can be a one-time, or a monthly contribution, to help ensure we’re here through this crisis. To donate or for more information, click here.

Sponsored content

Other items that may interest you