Five Towns schools focus on students’ mental health during the pandemic

The first of two stories examining student mental health.

The nearly year-long coronavirus pandemic has affected every facet of everyday life — especially education, and one of the country’s most vulnerable populations, students.

The upheaval began when schools shut down last March and shifted to remote learning, and it continues this school year, with multiple modes of instruction, in person and online.

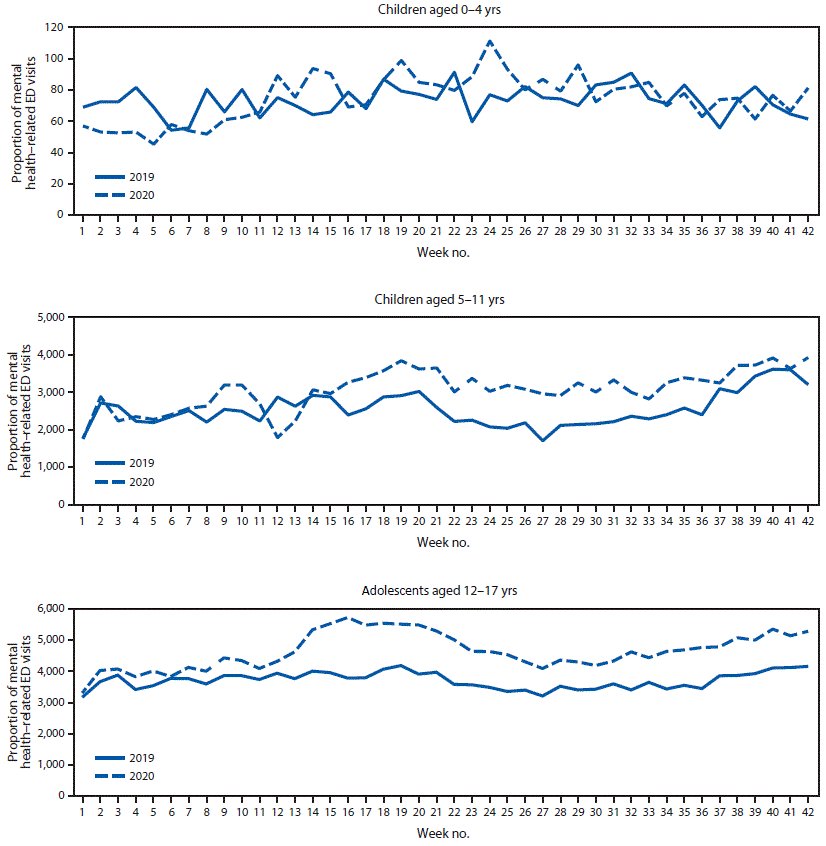

From April to October 2000, mental health-related hospital emergency department visits rose 24 percent for children ages 5 to 11 and 31 percent for adolescents and teens ages 12 to 17 compared with the same period in 2019, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Remote learning truly makes me feel alone and just stuck to the computer all day,” Elizabeth Zemlyansky wrote in an email to the Herald. The Hewlett High School junior, who began attending school in person last September, shifted to remote learning a few months later be-cause, she said, she couldn’t risk being infected with Covid-19, having to quarantine and not being able to take standardized tests. She is now on Hewlett High’s hybrid schedule.

When schools initially closed last March, the focus was on the transition from in-person instruction to remote learning, and the challenges ranged from ensuring that teachers and students were properly connected on Zoom and other platforms, to making sure that students had a stable environment for learning, to getting them the necessary digital devices, such as Chromebooks.

Laura Peterson, executive director of special-education services in the Hewlett-Woodmere School District, said there were concerns about how to remain linked with students after the buildings closed. “The wellness staff quickly found that they were able to connect with their students via phone or videoconference and maintain that connection,” she wrote in an email. “Ensuring that continuity was priority and was helpful to the students.”

Emphasizing that no one knew how long schools would be closed, Talya Braunstein, a Lawrence district psychologist assigned to the Brandeis School — a Jewish day school in Lawrence with pre-K through eighth-grade students — said her initial emphasis was on supporting parents as well as teachers in order to establish and maintain a healthy environment for the children.

“I was mindful that parents were trying to manage their own anxiety and juggle a new work-life balance …,” Braunstein emailed. “I tried to encourage parents to focus on what was in their control, manage their expectations of themselves and their children, and to make time to take extra care of themselves. I felt that that the best way to support my students was to support the adults in their lives, as we know children look to the adults to understand how to respond during a crisis.”

Hewlett High sophomore Brooke Touti said that when the pandemic began, she was unsure how she was going to handle her academic work while at home. “I could see that my mental health was influenced (negatively) because of not being able to interact with my colleagues and mentors on a day to day basis,” she said in an email. “I was able to keep my grades as high as I possibly could but, I was not enjoying anything I was doing.”

Lawrence School District psychologist Karen Mackler said that familiar student learning issues, such as attention-deficit disorder, have been exacerbated by the shift to remote learning. “It’s difficult to be on the computer so long,” she said, adding that in a typical school day, students, especially special education students who are in school, progress more than those at home.

At the Shulmaith School for Girls in Cedarhurst, fourth-grade teacher Shoshana Gross said that when the pandemic started and the Jewish day school was in remote mode, her students were “very anxious, very nervous and very worried, as learning over Zoom was difficult.”

“Any time you have to quarantine and you may have Covid, there are all these fears,” said Gross, who on Super Bowl Sunday took part in a virtual workshop that addressed mental health given by Hidden Sparks, a Manhattan-based nonprofit that trains teachers.

“The fear of having no social interaction, and now going to school [and] having a Plexiglas barrier, and how is that going to work, how normal is that?” Shulamith’s student population ranges from early childhood to high school.

Braunstein said that students who experienced social anxiety or had trouble connecting with their peers before the pandemic were “particularly lonely” without the structure that the typical school day offers.

“Students who struggled academically, particularly students who struggled with focusing and attention, found virtual learning to be virtually impossible, preventing them from learning and advancing along with their classmates,” she said. “… In comparison, students without such pre-existing challenges fared well.”

“Children are far more resilient than we anticipate them to be in the face of challenges,” Braunstein added, “and most adapted to their new realities perhaps even more swiftly than their parents and teachers.”

Next week: Planning for and handling a new school year.

Have an opinion or a story to tell about student mental health? Send a letter or story to jbessen@liherald.com.

48.0°,

Overcast

48.0°,

Overcast