Freeport’s amusement park: A blast from the past

Freeport’s once historic summer destination

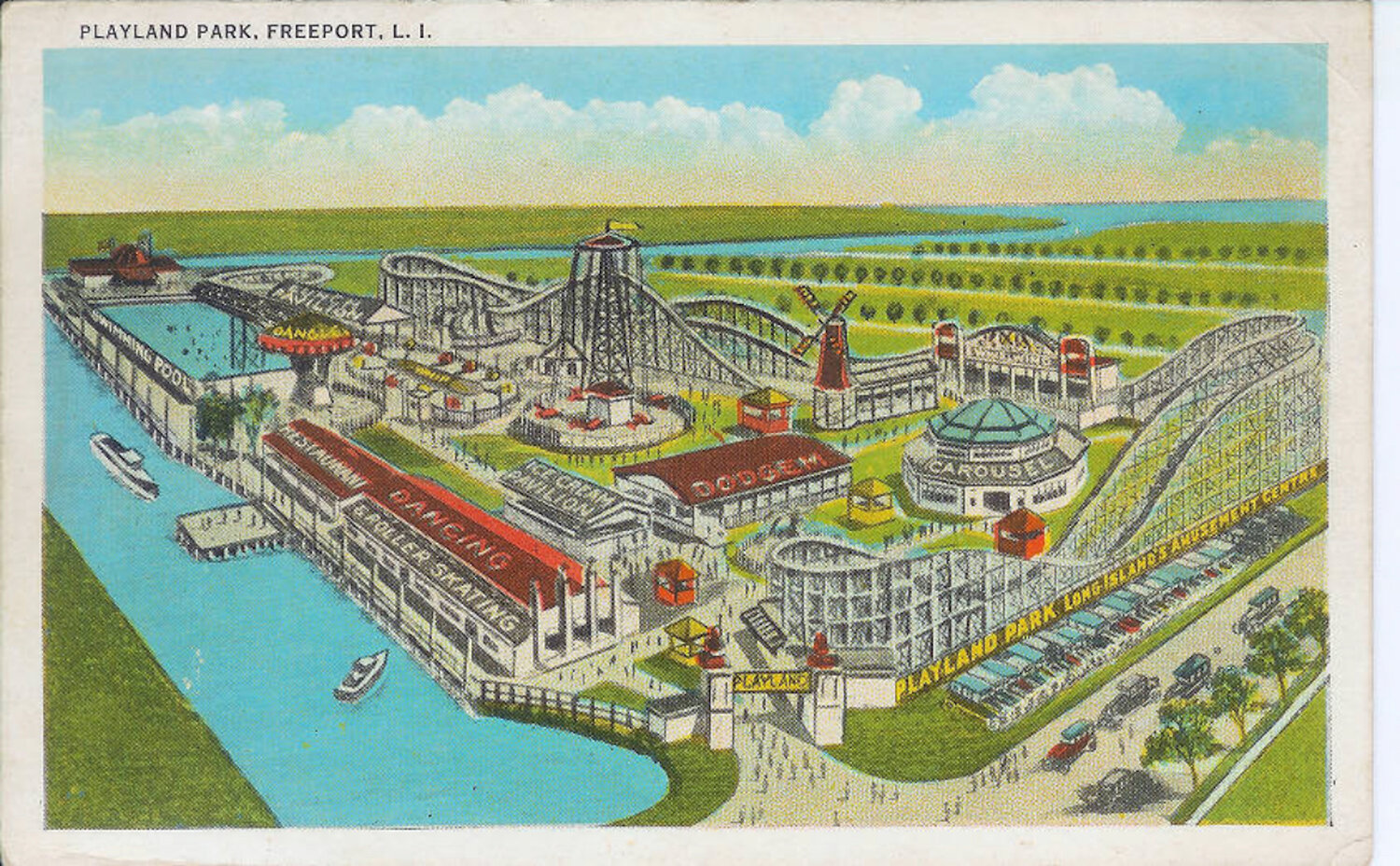

Playland Park, a once enchanting amusement park on the Freeport shoreline, transformed the village into a thriving tourist destination.

“It was the Hamptons before the Hamptons,” Regina Feeney of the Freeport Historical Society declared, in remembrance of Playland Park, referring to the bygone era of Playland

Playland Park, once a lively amusement park reminiscent of Coney Island, delighted visitors on South Grove Street that now known as Guy Lombardo Avenue and Front Street.

Opening its doors on May 26, 1923, the park spanned nine acres and featured a range of attractions, including a rollercoaster, carnival booths, a dance hall, a giant swing, a carousel, and even a bathing facility. The venture was the brainchild of a group of influential South Shore businessmen, including Harry Barasch, Samuel S. Geer, Charles Davey, Edward F. Goldman, and Richard Sanneman.

The initial purchase of the land, which cost $40,000, provided the foundation for this entertainment hotspot. During its prime, Playland Park achieved remarkable success, with annual gross receipts reaching $100,000 at its peak.

Notably, Playland Park welcomed renowned actor and competitive swimmer Johnny Weissmuller, who showcased his aquatic skills in the park’s pool during the mid-1920s. In 1928, the pool hosted the inaugural Nassau County interscholastic championship swim meet, solidifying the park’s reputation as a prominent regional destination.

“This was the preferred summer destination for many people,” Feeney said. “The main reason for this was the absence of air conditioning at the time. Individuals, including actors, sought refuge from the heat by escaping to places like Freeport. The theater industry, in particular, experienced a lull during the summer months as theaters lacked air conditioning. So, many performers and theater professionals went to coastal areas, such as Freeport, to cool down basically.”

Freeport’s allure as a tourist destination has always been tied to its captivating waterfront. As early as 1839, when the area was known as Raynor town, it attracted sportsmen in pursuit of fishing and hunting opportunities. The 1870s witnessed the emergence of gun and yacht clubs in Freeport and the surrounding meadowlands.

The transformation of south Freeport gained momentum in the 1890s, thanks to the efforts of John J. Randall and his business partner William G. Miller, who embarked on canal dredging and residential construction projects. By 1899, trolleys had become a convenient mode of transportation in Freeport, ferrying passengers to the end of Woodcleft Avenue, where ferries awaited to transport them to popular beaches like High Hill Beach and Nassau-By-The-Sea.

To cater to the influx of visitors, numerous hotels were erected, one of which, the Woodcleft Inn, proudly hosted Mayor Robert A. Van Wyck for two seasons. On August 3, 1898, Mayor Van Wyck’s heroism was on full display as he rescued three girls from drowning in Woodcleft Canal.

During the 1910s, Freeport boasted several open-air theaters, often referred to as airdome theaters, providing entertainment through movies and occasional vaudeville acts.

Unfortunately, Playland Park’s fate took a turn for the worse due to the economic downturn of the Great Depression and fierce competition from the newly established state park at Jones Beach. In 1931, disaster struck when a devastating fire engulfed the park, leading to its ultimate demise.

Coincidentally, on the day of the blaze, the Freeport Fire Department was filming

“The Freeport Story” at Maple Street and Mill Road. The film production company, a subsidiary of the Fox Film Corporation, had stored equipment in Playland Park’s pavilion. Tragically, the fire consumed the pavilion, valued at $30,000, and destroyed equipment worth $100,000. The fire was attributed to an electrical short circuit.

In 1933, the Playland Park property was purchased for residential development by Ernest S. Randall. However, a year later, following Randall’s passing, all of his real estate holdings, including the former amusement park, were sold at auction, signaling the end of an era.