Gách inspired by North Shore landscapes

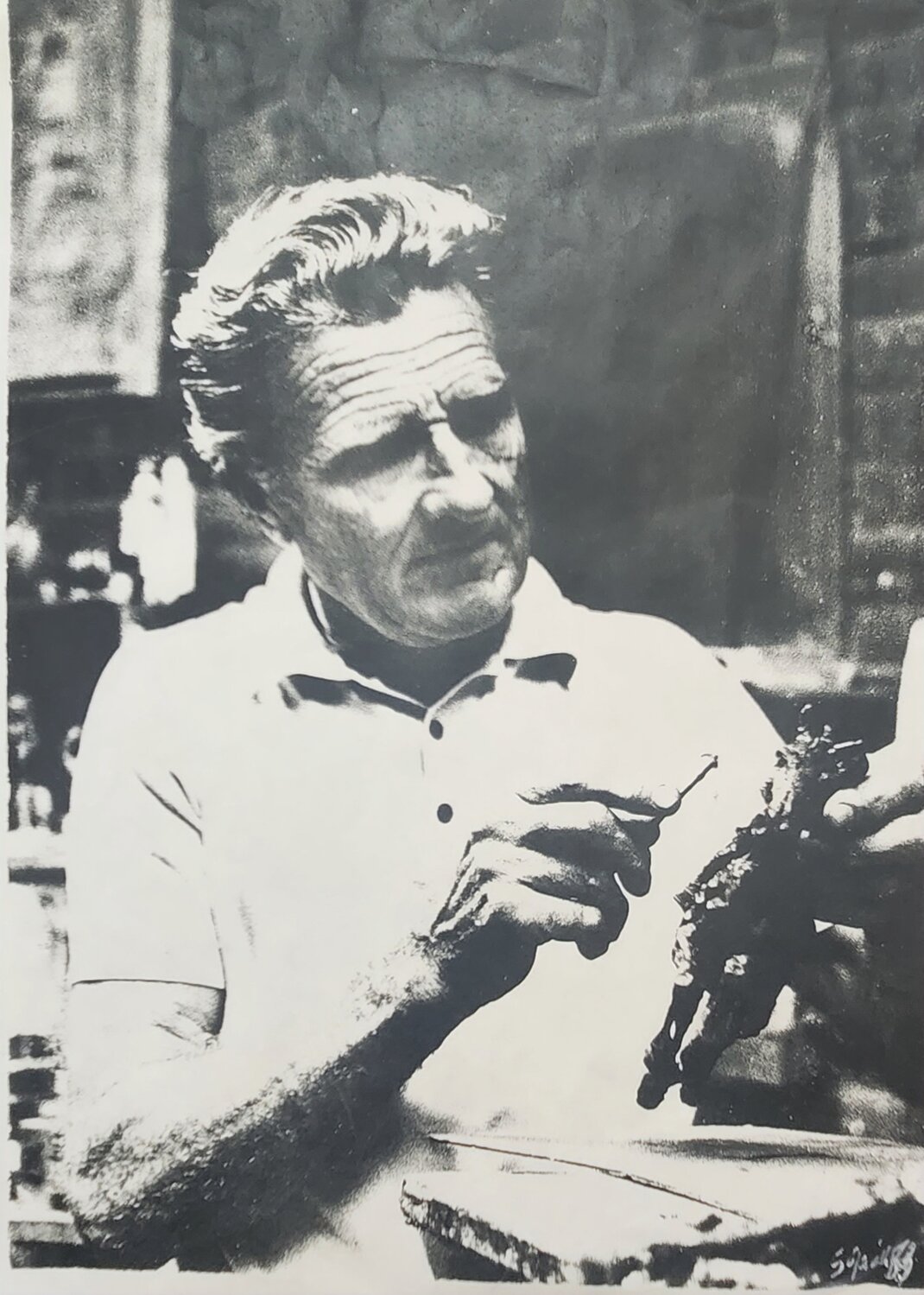

Many of the paintings and sculptors created by George Gách are on permanent exhibit at the North Shore Historical Museum in Glen Cove. For many years, the Roslyn resident created landscapes that often-depicted landmarks local to the North Shore, especially in Sea Cliff and Oyster Bay. His style is both classical and impressionistic, and his subjects included animals, flowers, dancers, musicians, skaters, athletes and cowboys, to name a few. Gách utilized a variety of locations, including Long Island, Bermuda, Mexico, upstate New York and Florida. And he had 35 one-man shows.

Born in Budapest, Hungary in 1909, he was the son of a prominent Hungarian sculptor and apprenticed under his father’s tutelage until the age of 18. Gách attended the Fine Arts Academy in Budapest, where he later became an assistant professor. But his career as an artist emotionally solidified with him when he served as a pilot during World War II, when he was shot down and imprisoned by the Russian Army in 1944.

Footage from the artist’s 80th birthday shows him recalling the pivotal moment in his life. He remembers crashing on the side of a mountain and turning off his engines for a safe landing. Not long after the crash, Russian soldiers, who had their guns raised ready to fire, approached him. But the soldiers saw Gách laughing among the smoldering wreckage, arms held high, and ready to surrender.

Confused, the Russian soldiers asked him why he wasn’t acting in fear. He replied that he wasn’t scared of them; he was happy to be alive after the crash.

Gách was taken as a prisoner back to the Russian camps and was confined to a small room with a heavy metal door. This door had a small hole which he convinced his captors to slip paper and pencils through. For weeks, he drew portraits of the guards with his minimalist tools. The guards were so impressed by his talent that they agreed to rotate their shifts every four hours so they could have their turn seeing a glimpse of themselves through the eyes of a classically trained artist.

When Gách saw his father after his release, he said he was convinced that he was finally an artist because his art enabled him to survive captivity in the Russian prison.

Gách returned to Budapest, and in 1947, feeling threatened by the Communist regime, fled to Beirut, Lebanon, where he became a pilot for a Middle Eastern airline and also taught at the Academy of Fine Arts.

In 1952, Gách relocated his wife and three children to the United States and devoted himself entirely to painting, sculpting and art instruction. He claims he would draw at least six hours per week to keep what he learned sharp in his mind.

“I can now fly as high as I desire with the fantasy provide by my work,” Gách’s website quoted him saying.

Among Gách’s many distinguished awards are the Audubon Artists Medal of Honor in 1966, the Gold Medal of the National Sculpture Society of New York in 1970, and the Percival Dietsch Award of the National Sculpture Society of New York in 1974.

He continued to paint, sculpt and travel widely throughout Europe, North and South America and the South Pacific. Among the works he produced in Beirut was a bronze bust of the president of Lebanon.

Gách’s died in 1996. His legacy lives on through his work and family lineage. His daughter, Susie Gách Peelle, a Locust Valley resident, began drawing at age 5, and painting at 12. She posed for her father, observed his lessons, demos, and outdoor classes.

Her subjects vary greatly, as well as her mediums, which include oil, acrylic, pastel, lead, conté, ink, gouache, graphics, and mosaic. She said her father dissuaded her from working in metal sculpting, saying the material was too heavy to lift.

During a George Gách exhibition at Nassau Community College in the early 90s, he advised his daughter that an artist’s only handicap is material. His most sage advice to his audience came from his philosophical insight about people.

“The difference between people is not race or nationality,” Gách said. “The difference is between who are creative people and who are destroyers.”

57.0°,

Partly Cloudy

57.0°,

Partly Cloudy