Lynbrook eye doctor recalls conducting first laser surgery

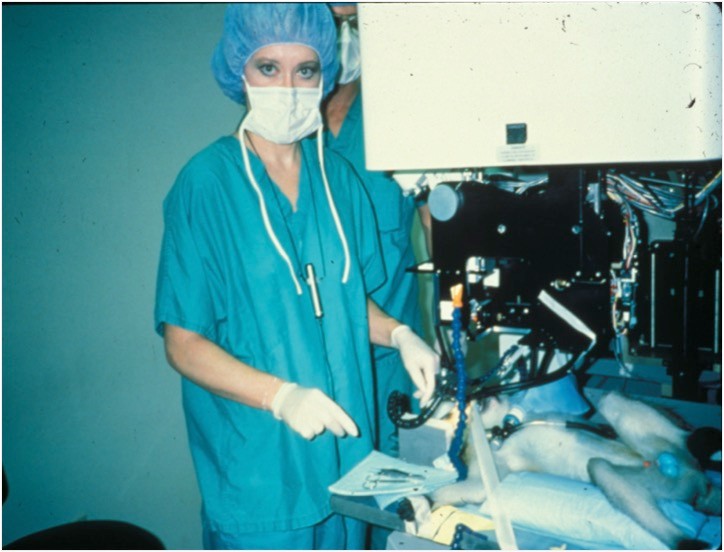

Dr. Marguerite McDonald knew that she was a part of history. There she was, an ophthalmologist in her 30s, preparing to conduct the first laser eye surgery on a human.

It was March 25, 1988, a day that McDonald, who now practices in Lynbrook, said she would never forget. That day, she said, she and her research team at Louisiana State University were offered a gift. It was a woman named Alberta Cassady, who was about to lose an eye to cancer surgery and volunteered to become the first human test subject for laser eye surgery.

“I was excited and nervous,” McDonald recalled days after the 30th anniversary of the operation. “Alberta was a very quiet, stoic woman, but she was aware that she was playing an enormous role in scientific history.”

Laser eye surgery is commonly used today to correct vision and eliminate the need for glasses and contact lenses by reshaping the cornea. McDonald now works at Ophthalmic Consultants of Long Island, on Merrick Road in Lynbrook, and also has offices in Manhasset and Garden City, in addition to teaching ophthalmology at New York University. But it was her work at LSU that put her on the map.

In 1983, she read an article published by Dr. Steve Trokel, her former professor at Columbia University. Trokel wrote that he had tested an excimer laser, which was used to make computer chips, on a cadaver, and discovered that it could be used for laser eye surgery. “I was completely mesmerized by this paper,” McDonald said.

McDonald, who is originally from Chicago and was a professor of ophthalmology at LSU at the time, contacted Trokel and suggested that they work together, because she had access to many animals at the Delta Primate Center in Covington, La., which they used to humanely test the laser. Teaming up with renowned physicist Dr. Charles Munnerlyn, they began testing the lasers on the eyes of pig and cow cadavers. Then, as they grew more confident in their research, they moved on to live rabbits and monkeys.

“We were plodding along, trying to work out the details,” McDonald recounted. “Then we came across quite an astonishing opportunity.” That opportunity was Cassady, who had been diagnosed with orbital cancer, which wrapped around one of her eyes. She was days away from having the eye surgically removed, and volunteered to be a subject.

“We simply could not believe it,” McDonald said. “We were numb with grief for her, and she comes up with this extraordinary offer.” The U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted them permission to operate on Cassady, and she was rushed to the primate center, where researchers from LSU and Tulane University were working — and where monkeys and chimpanzees that were being tested shrieked and spit at the stranger. “We got her under the laser, and we did the first treatment in the world on a living eye,” McDonald said.

She was confident that the procedure would work, because there had been thousands of successful tests on animals and cadavers. Cassady didn’t appear nervous, McDonald recounted, describing her as a woman with gumption who was “remarkably calm," said little, didn’t wear makeup, wore plain clothes and was “country-like.”

Cassady had 20-20 vision, so the doctors had to pretend that she was near-sighted and dialed up a prescription for someone who was, which actually made her vision blurry. The procedure was successful, and the FDA was impressed with the results.

Dr. Richard Lindstrom, the clinical spokesman for the American Academy of Ophthalmology, praised McDonald for having an ethical, science-based approach to her research and testing. “Like every pioneer, she weathered the storm and did it in a very classy fashion, with openness and transparency,” Lindstrom said. “She continues to be a major contributor to the field.”

Cassady lost her battle with cancer a few months after the groundbreaking surgery, and a laser lab at LSU was named in her honor.

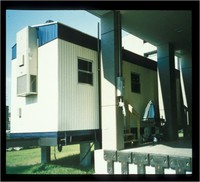

The researchers began working in a trailer at LSU that was next to a trash compactor, which inadvertently led to a discovery. The researchers found that when the trash compactor was operating, it shook the trailer, which made the laser wobble instead of shooting straight down into the patient’s eye. McDonald said that when the trailer wasn’t vibrating, the treatments were not as smooth and the results not as good. This led to a smoothing of the procedure so the ridges the laser produced were eliminated.

According to Lindstrom, there are 650,000 laser eye surgeries in the U.S. each year. McDonald recalled, however, that there was plenty of opposition to the practice in the 1980s. “A lot of the conservative ophthalmologists thought that any kind of surgery to get rid of glasses or contacts was frivolous at best, and unethical at worst,” she said.

She added that a well-known doctor lambasted her and the use of lasers in an article in a respected journal. McDonald said that early in her research, there were some negative results during testing on animals, and she lost part of her team. “There were some dark times,” she said. “There were a lot of things we didn’t know. I just said, ‘Let’s keep trying different things.’ I knew it would change people’s lives. I knew it was going to work.”

Three decades after Cassady’s operation, many advancements have been made. The lasers now have eye trackers, there are treatments for people who have irregular or warped corneas, and doctors can treat astigmatism, a defect in the eye’s lens that distorts vision.

McDonald and her husband, Dr. Stephen Klyce, whom she met when he became part of her research team and worked with her on Alberta Cassady’s operation, moved to Port Washington in 2006, having left New Orleans after their home and practice were damaged in Hurricane Katrina. They continue to correct vision with lasers 30 years after their first operation, all because of Cassady’s bravery. “We wouldn’t be where we are today without her,” McDonald said. “She was pivotal.”