Elmont Library offers rare view of presidency

All men not created equal to founding generation

“I hope it will not be conceived … that it is my wish to hold these unhappy people in slavery,” George Washington wrote to Arthur Young in December 1793, six years before his death. “I can only say that there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it.”

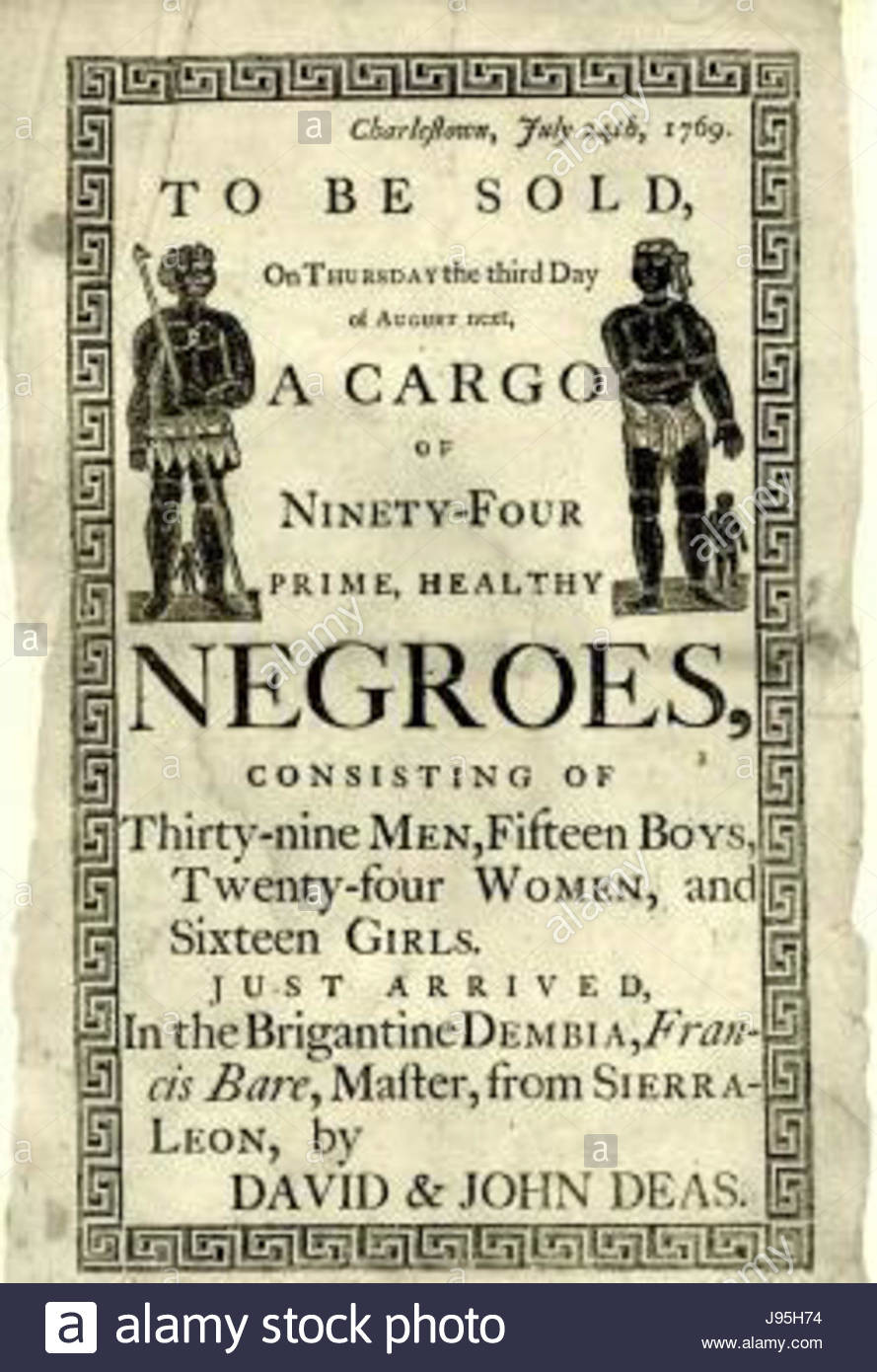

Washington was a long time arriving at this point of view, as shown by Marilyn Carminio in a fascinating presentation at the Elmont Memorial Library on Feb. 9, entitled “Slavery and the Presidency.” Initially, Washington was very much a man of his class and time. Slavery was so interwoven into the Tidewater culture of the Virginia in which he grew up that he would no more have questioned it than he would have questioned the king or the church. It was regarded as perfectly natural to the order of society, according to Carminio, so much so that the Washingtons, Jeffersons and others of their class would have bought, sold, gifted or traded slaves with no more thought than if they had been pieces of furniture or livestock.

Washington became a slave owner at the early age of 11, when, on his father’s death, he inherited the family’s 280-acre farm and its 10 slaves. As a young man, he bought a further eight slaves. He became a significant slave-holder in 1759, when he married the wealthy widow Martha Dandridge Custis and became master of her 84 slaves. From then until the outbreak of the Revolution, he bought or traded for at least 40 more human beings. From that point on, most of the increase in his slave holdings was the result of births among the population at Mount Vernon.

Washington was not an easy man to work for, according to Carminio. It is less clear whether this was directed specifically against slaves or was simply a part of his general punctiliousness. He was known to be hard on his subordinates as well — and on himself. It is certainly true that he punished runaways very harshly; but he was equally unforgiving in his treatment of deserters during his periods of military service.

Washington’s views on slavery underwent a radical transformation during the Revolution. Writing to James Madison in 1788 of this period, he said, “Liberty, when it begins to take root, is a plant of rapid growth.” And although he’d been a slave owner for more than 30 years at the outbreak of the war, he could confide in a cousin in 1778, a scant three years after the war’s outbreak, that “more and more, I long to get clear” of the ownership of slaves.

Up until the end of the Revolution, slaves in Virginia could receive manumission — formal release from servitude — only by special act of the governor and his council, according to the Mount Vernon web site. The legislature changed this law in 1782, and by the time of Washington’s death in December 1799, he had freed all 153 slaves whom he owned outright. On the other hand, he brought seven slaves to serve in the presidential mansion during his term as chief executive, including his chef, Hercules. (Carminio said masters often gave slaves heroic names from antiquity as a way of mocking them.) So while he may have been willing to release them from their condition when he no longer needed their service, no evidence exists that he ever freed any slaves during his lifetime.

The slaves belonging to the estate presented a more complicated problem, Carminio said, because many had intermarried with those belonging personally to Washington. Families were broken up as members were sold to different owners. Carminio detailed a number of cases where slaves who had been freed worked long years to purchase the freedom of family members who had been sold on. Of the many brutal and ignominious practices typical of slavery, this break-up of families was one of the most heartbreaking.

Jefferson and Madison

“Never did a man achieve more fame for what he did not do.” With those scathing words, the 19th-century Virginia abolitionist Moncure Conway condemned Thomas Jefferson, first for his hypocrisy, and finally for his silence in the last 20 years of his life on the subject of slavery. It was Jefferson, after all, who penned the words even the most obtuse U.S. schoolchild knows by heart: “All men are created equal,” And it was President Jefferson who in 1808, signed the law abolishing further importation of slaves into the U.S. Yet, this same Thomas Jefferson bought and sold more than 600 human beings in the long course of his life; whose Monticello mansion was built brick by brick by slaves; and who freed none of them in his will -- not even his longtime bedmate, Sally Hemings, nor any of the six children he allegedly sired of her.

The exact nature of the relationship between Jefferson and Hemings has never been clear, Carminio said. On the one hand, she did consent to return to Virginia from France, where she was legally free. This suggests a strong emotional bond. Did Jefferson promise her or her family freedom? But as his debts mounted toward the end of his life, his slaves were among his most valuable possessions. Within three years of Jefferson’s death in 1826, all his slaves had been sold and dispersed.

James Madison, likewise, never freed any of the 100 slaves on his 4,000-acre estate at Montpellier. Citing a new biography, “The Three Lives of James Madison,” by Harvard University Professor Noah Feldman, Carminio described how “many of the founders felt ashamed of slavery, as a number of civilized nations began to outlaw the practice; they just didn’t feel sufficiently ashamed to do anything about it.” His widow, Dolley Madison, always a notorious spendthrift and always short of cash, sold most of her late husband’s property, including his slaves, without regard to families or relationships.

Of the founding generation of the American republic, only John Adams, the second president, never owned any slaves, despite the fact that slavery was legal in Massachusetts Bay Province at the time of his birth. And the Adams family was not wealthy. A near-exact contemporary of Washington and only a dozen years older than Jefferson, he nevertheless paid for free labor to help on the family’s Braintree, Mass., farm, rather than follow the cheaper practice of buying other humans. His son, the sixth president John Quincy Adams, likewise never owned any slaves, although it is likely both father and son were served by slaves during their tenures in the 81630A FSE Slavery81630B FSE House, as well as in ambassadorial postings abroad.

According to Carminio, slaves built nearly the entirety of the original Washington City, including the Capitol and the White House, and served in the presidential mansion up until the outbreak of the Civil War. It was a house slave named Sookie who warned in 1814, that “The British are coming,” ironically enabling Dolley Madison to save crucial documents and artifacts, such as the Constitution and the famous Gilbert Stuart portrait of Washington, before the invaders burned the house to the ground.

Of the first 12 presidents, only the Adamses never owned slaves. Of the first 18 U.S. presidents, 13 were at one time slave owners, including Martin van Buren, who owned one, and Ulysses S. Grant, who owned five during the years before the Civil War, when he worked his own small farm. Neither van Buren nor Grant were Southerners. And while Abraham Lincoln never owned slaves personally, his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, came from a slave-owning family.

Aftermath

The 13th Amendment to the Constitution was passed by Congress in 1865, and became law in 1868. During the early period of Reconstruction, African-Americans began to acquire some small measure of equality, achieving a number of firsts. Rebecca Lee Crumpler became the first African-American physician of either sex in 1864. Richard Theodore Greener was the first African-American to graduate from Harvard College, in 1870. Hiram Revels was elected to the Senate from Mississippi in the same year.

Most of these gains were rolled back with the end of Reconstruction in 1876. From then on, Jim Crow laws systematically disenfranchised African-Americans, culminating in such Supreme Court decisions as Plessey v. Fergusson, in 1896, which ushered in more than a half-century of segregation in U.S. schools.

One of the few bright lights was Booker T. Washington. Born into slavery in Virginia, in 1856, he subsequently became director of the Tuskegee Institute, building it into one of the most successful black institutions of higher education in the U.S. After his autobiography, “Up From Slavery,” appeared in 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt invited him to the White House. He was not the first African-American to be invited to the White House, but he was the first to be invited formally with his family to dine with the president. Carminio showed examples of the vitriolic racist rhetoric that appeared at the time.

Sen. John Mc Cain, Republican of Arizona, referred to this incident in his 2008 concession speech to President-elect Barack Obama: “A century ago, President Theodore Roosevelt’s invitation of Booker T. Washington to visit — to dine at the White House — was taken as an outrage in many quarters. America today is a world away from the cruel and prideful bigotry of that time. There is no better evidence of this than the election of an African-American to the presidency of the United States. Let there be no reason now for any American to fail to cherish their citizenship.”

39.0°,

Fair

39.0°,

Fair