Giving the town all he's got

After surgery, RVC native will continue training TOH lifeguards

The two columns of gray T-shirted, sweat-drenched runners you may see hustling across the sand on a Town of Hempstead beach early next month will not be the Marines, but rather the town's rookie lifeguards, being drilled by Training Officer Andrew Rinn. For two weeks Rinn will beat the teenagers down and build them back up, in the ocean and out, weeding out quitters, building a team. He'll be the one in a lifeguard uniform, though looking, frankly, with his shoulder-length black hair, more like Russell Brand's athletic older brother than a beach captain.

But don't be fooled, even if you notice a limp or some other oddity in Rinn's running gait. At 42, a lifeguard for 26 years, a phys. ed. and health teacher and the track and cross-country coach at East Rockaway High School, he is one of the town's alpha guards. "Andrew is a leader," says Mal McGarry, the Town of Hempstead's aquatic coordinator. "And he knows everything, from the tides to the composition of the sand. He's the most knowledgeable lifeguard we have."

Rinn has added some pain-management skills in recent summers, much to his dismay. Ravaged by arthritis 30 years too soon, the cartilage in his hips deteriorated so rapidly that by last fall the pain of the slightest misstep jolted through him like electricity and he couldn't even make himself comfortable in the water, let alone in any position on land, standing, leaning, seated or supine. Four months after gutting out his ninth year of rookie training, he underwent major orthopedic surgery, a bilateral hip resurfacing, a still relatively rare procedure that is becoming a useful alternative to hip replacement for younger osteoarthritis sufferers.

"It'll allow him to be more active," says Dr. Scott Marwin of NYU's Hospital for Joint Diseases, who in several hours in a Manhattan O.R. last Nov. 17, smoothed and capped the tops of both of Rinn's hip bones and embedded metal cups in his hip sockets, to give the joints new life. Marwin likened Rinn's pre-op X-rays to those of a 90-year-old, but he's seeing more of that these days. "Patients like Andy are getting much more common," he said. "They're younger and they're very active."

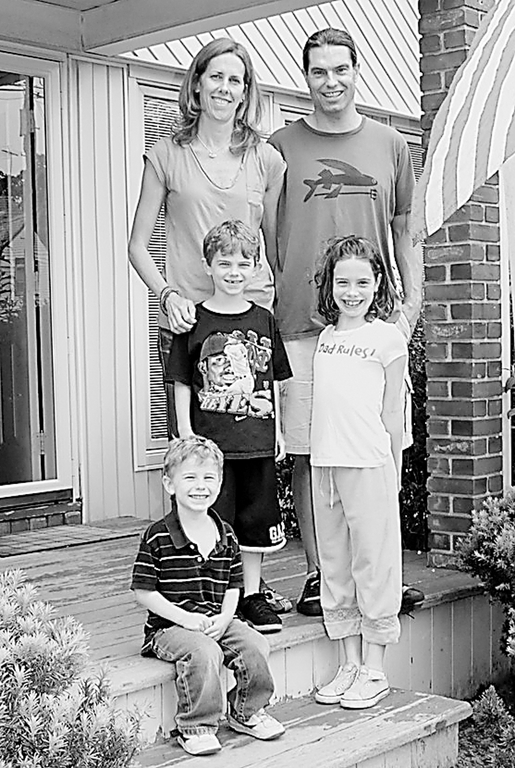

"Active" falls well short of describing Rinn, who lives in Oceanside with his wife, Deirdre, a teacher at Wilson Elementary School, and their three children. A wrestler, football player and track star at South Side High School, where he graduated in 1985 and began his coaching career nine years later, he has ridden skateboards and snowboards as fast and as high as possible since he was a kid. He has excelled in the most rarefied skill in lifeguarding, rowing an 800-pound dory. He is as strong on a bike as he is in the water, and became one of the top triathletes on Long Island, winning the Town of Hempstead Triathlon three straight years, from 1993 to 1995.

By all accounts, Rinn is an improvisational athlete as well, an inventor of challenges, a taker of dares, some smarter than others. And he has the scars to prove it. His hip problem may have been impossible to predict — the causes of arthritis remain a mystery even to the medical community — but Rinn doesn't deny repeatedly putting his body to the test over the years.

When he was 12 he fell from a homemade zipline strung from the roof of a neighbor's house to a tree in the yard, breaking a wrist and suffering a concussion. Attempting a steep skateboarding drop in college, he bounced off the concrete and dislocated a shoulder. When Baldwin's skate park opened eight years ago, he tried the same sort of move — dropping into a six-foot half-pipe —and re-dislocated the shoulder. "He was only gone 45 minutes," Deirdre recalls. "He called me from the ambulance."

Rinn has crashed into safety fences on ski slopes and launched dorys into thin air off hurricane-sized ocean swells. The bigger the wave, the more Andrew wants it, says his younger brother Keith, 39. "He's bodysurfing it — he's boat-surfing it," Keith says. "It's the same way with skateboarding and snowboarding."

And anything else that gets him stoked. That's Rinn — his legs, anyway — in a photo on the jacket of the punk band Gorilla Biscuits' 1989 album "Start Today." He was in midair, diving off the CBGB stage, when the photo was taken.

"I wouldn't say he's abused his body, but he's used it well," says his father, Greg, a Rockville Centre trustee from 2001 to 2005.

"He's challenged his body," adds his mother, Jane, the former Jane Yannelli. They still live in the same house on Muirfield Road where Andrew, his older brother Greg, 45, and Keith grew up.

Andrew has twice run the New York City Marathon, and after the 2005 race, his right hip started bothering him. He ran through the pain, as runners do, but he had telltale range-of-motion problems as well. "When I'd put my shoes on, I had to twist my body weird," he recalls, "and I couldn't cross an ankle over the opposite knee." He felt a throbbing pain deep in his hip, at first just when he was moving around but eventually all the time.

In 2008 he was told he needed hip replacement surgery. Then he and Marwin began discussing resurfacing. Whatever the procedure, Rinn was ready. By last summer, when he struggled through the rookie training, "it was bone on bone," he says, "and the pain was excruciating."

"We'd tell him, 'We'll give you an ATV.' 'We'll give you a truck,' but he'd say, 'No, no, I'll run along with them,'" recalls McGarry. "He hobbled through it, but he never complained."

After the surgery in November, Rinn lay in a hospital bed for a week with not much to do but think. "I'd tell myself that I was gonna get back to the beach," he says. "Then I'd think, Can I make it back?" His rehabilitation began with hours of physical and occupational therapy at the Rusk Institute of Rehabilitative Medicine. He used a walker for 10 days, then spent a month on crutches. He got back into the Hofstra pool before Christmas, and did three and a half months of rehab at Professional Orthopedic and Sports Physical Therapy in Garden City.

Marwin gave Rinn the OK to start running again just three weeks ago, so how ready he'll be for the rookies is anyone's guess. Whether he's leading or following, though, they will run and swim until they're ready to drop. "I do crush them the first couple days," he says. He'll send them out to swim around a jetty, for example, at a time of wind and tide when only he knows that their exhausting effort will be futile, and the ocean will push them backward. The next time, he'll show them when and how to make it around the rocks. "There are a lot of teachable moments in rookie training," he says.

The trainees will learn rescues with torpedo buoys and surfboards. They will drag logs through the sand with chains. Rinn will take on every challenge with them, and test their skills frequently. "If any part is not sufficient, you do it again," says David Thompson, a guard for six years who vividly remembers the training. "If you forget your whistle, you do it again." But it's all about getting through it as a team, Thompson adds. The guards bond; they come together — and they'll follow Rinn anywhere.

By the time he is done with them, Rinn is what McGarry describes as "the beloved drill sergeant." "He's everything to them," McGarry says. "They don't move till he looks at them. When he looks at them, they move."

Comments about this story? JHarmon@liherald.com

75.0°,

Partly Cloudy and Breezy

75.0°,

Partly Cloudy and Breezy