Friday, April 26, 2024

39.0°,

Fair

39.0°,

Fair

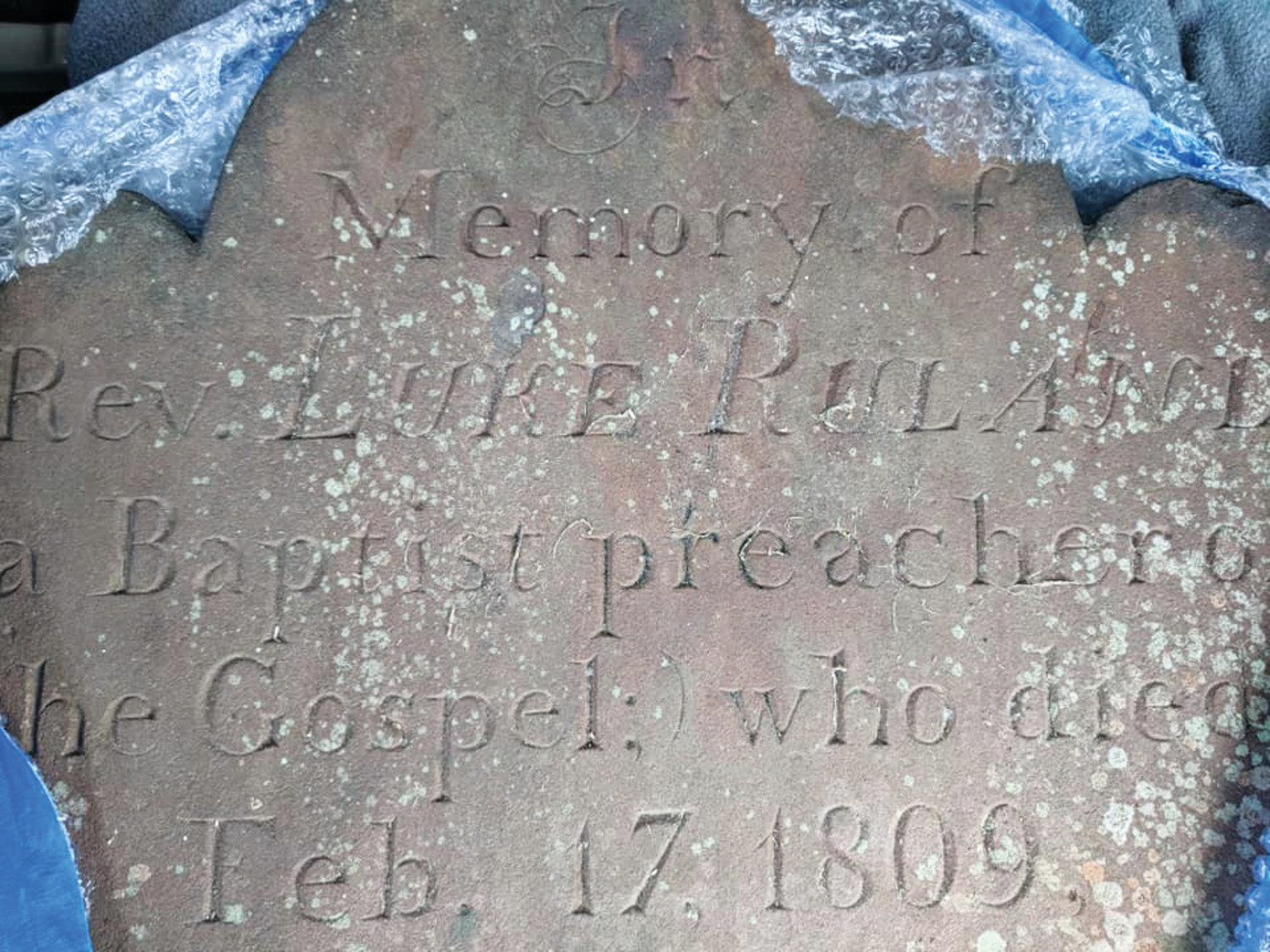

Headstone of Oceanside resident’s ancestor is returned after being missing for two decades

Oceanside resident Roy Ruland recalled that he and his brother Steve had long been curious about their family’s roots. Twenty years ago, Roy trudged through the unkempt Waverly Avenue Cemetery, in Patchogue, looking for the grave marker of the family’s oldest known relative: the Rev. Luke Ruland, the first Baptist minister in Patchogue and a Revolutionary War soldier.

After a dizzying search that took many hours, however, Roy discovered many of his ancestors’ gravesites intact, but one sandstone marker was missing: that of the late pastor, an ancestor of the Rulands that Roy and Steve traced back seven generations.

“We always wanted to know where the Ruland name came from,” explained Roy, 54, a retired NYPD detective, noting that the brothers traced it back to France in the 1500s. “We weren’t sure what it was. My father didn’t know. My grandfather didn’t know. . . . When the marker went missing, I searched and searched, but it was gone.”

The Ruland brothers’ curiosity about their history led them to start tracing their ancestry in the mid-1990s, long before it became easy to do so on the internet. Steve, now 56, began creating a family tree and discovered that many of their ancestors were buried at the Patchogue cemetery, where they went several times and saw each marker, including that of the Rev. Luke Ruland before it mysteriously disappeared. By searching through records, the Rulands learned that the pastor served as part of a militia in the Battle of Brooklyn during the Revolutionary War and became the first pastor of the Baptist Church in Patchogue in the 1790s.

“The religion was pretty new at that time, and they weren’t liked very much,” Roy said with a laugh. “There’s a lot of history in that cemetery, a lot of Long Island history in that cemetery.”

But 20 years ago, Roy recounted, he discovered that Luke’s headstone was missing. He said he thought that maybe vandals came in and stole it and that he was sad because the only memory he had of it was a picture. Roy said that last spring he continued to search for it with his brother, who is a retired NYPD sergeant and lives in Connecticut. They found a sign denoting a Cemetery Restoration Committee, which was working on improving the cemetery’s grounds. Roy said he began helping them with the site’s upkeep, but was beginning to lose hope of getting his ancestor’s headstone back.

Then, on Veterans Day, Steve received a call from Lynn Davis, the preservation director of the committee. Davis informed him that an unknown person had anonymously returned the headstone to the Burying Ground Preservation Group, a nonprofit in Southampton. Davis picked the headstone up and brought it to Roy, who said he was “elated” to be able to grip it in his hands after spending two decades looking for it.

“It was a miracle to me,” he said. “I couldn’t believe it. After 20 years, it was a long time. I’m just glad he’s back home.”

Davis said it was a special moment to be able to hand the stone over to a living relative, because she mostly deals with headstones that don’t have anyone searching for them. “Personally for me, to be able to go to the cemetery, take the stone out of my trunk and have a family member hug me was a pretty emotional thing,” she said. “You couldn’t contain his happiness.”

Roy said that the headstone was broken at its base, but was left in good condition. According to the marker, Ruland died in 1809 at age 78. The stone was inscribed with a statement that read, “I have finished my course. I have kept the faith.”

The Rulands and the committee are raising money to reset the headstone, and said that they hope to have a ceremony to do so when the ground thaws in the spring. Roy serves as the vice president of the auxiliary for the Oceanside Veterans of Foreign Wars post and said he has been using the organization as a vehicle to raise money to support the rededication. In addition, the committee raised $700 on Giving Tuesday, which will be matched by Facebook and PayPal, for the ceremony and the costs to repair the stone.

Roy said he was relieved to have the stone back, and that the cemetery is an important piece of Long Island history, noting that former veterans, slaves and suffragettes were buried there.

“Those laid to rest there are the people who made Long Island what it is,” he said. “You have to take care of your cemeteries, especially historic ones. You walk through that cemetery, and you just feel something.”

HELP SUPPORT LOCAL JOURNALISM

The worldwide pandemic has threatened many of the businesses you rely on every day, but don’t let it take away your source for local news. Now more than ever, we need your help to ensure nothing but the best in hyperlocal community journalism comes straight to you. Consider supporting the Herald with a small donation. It can be a one-time, or a monthly contribution, to help ensure we’re here through this crisis. To donate or for more information, click here.

Sponsored content

Other items that may interest you