History hidden in plain sight: Clear Stream Pond

By the early 1850s, Brooklyn was desperate for water. The borough’s well water contained too many particles of solid matter per gallon, rendering it unsafe to drink. Manufacturers also needed water to power their steam boilers and engines. In 1855, after years of failed committees, schemes, and company formations, the New York State Legislature passed an act allowing the incorporation of the Nassau Water Company. The NWC was granted the right to take water from Long Island ponds, springs, streams, and eventually driven wells via a system of underground conduits (the original design was open-air canals). The NWC board was reorganized a few years later into the Nassau Water Works of the City of Brooklyn. Most folks, however, referred to the NWW as the Brooklyn Water Works, Ridgewood Aqueduct, or Ridgewood System unofficial but accepted names.

A spring becomes a pond:

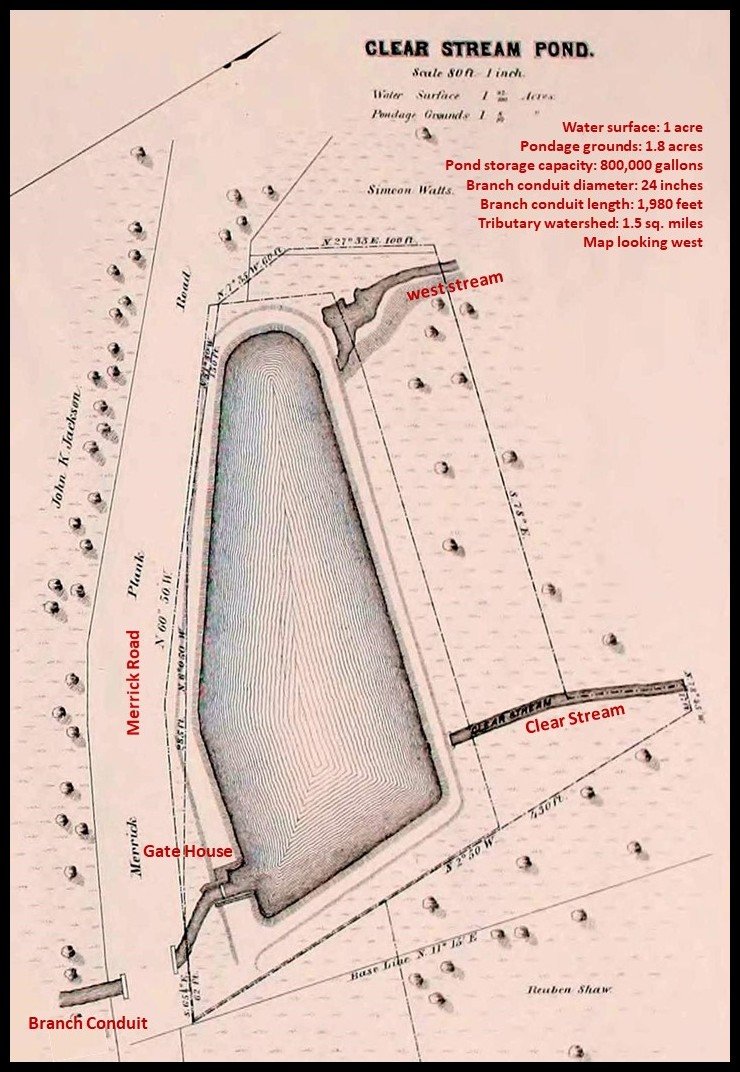

In 1858, a small plot of land on Merrick Road (between Arlington and Guenther avenues) that contained a subterranean spring, was purchased for $1,010 by the water works. The purpose of the purchase was to turn the spring into a pond. Cornell’s Pond (Arthur J. Hendrickson Park) and Watts Pond’s water rights (Mill Pond at Edward W. Cahill Memorial Park) were purchased in 1853 and 1858. These three sites comprised Valley Stream’s contribution to Brooklyn’s unquenchable thirst.

Fine sand and gravel covered the triangular-shaped plot. Although pervious materials, they retained impressive amounts of water. After a good rain, some of the water replenished the aquifer; the balance flowed along the sand’s surface, temporarily creating a spring that disappeared during droughts. Once excavated, the spring-turned-pond held 800,000 gallons of water. The Brooklyn Water Works christened the single-acre reservoir Clear Stream Pond. “It pours a stream as clear as crystal,” boasted The Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1859.

Two headwater streams:

In addition to rainwater, the new pond was fed from the north by two short and narrow headwater streams that formed a V at the center of the northern rim. Headwater streams originate inland. They collect water from rain, runoff, and snow melt. They, too, contain springs and rely on precipitation to keep full. The western stream ran along Arlington Avenue. Its headwater was at the juncture of Hunter Avenue and Fenwood Drive. The eastern stream, named Clear Stream, ran between Lyon Street and Guenther Avenue; its headwater was near the intersection of Shipley and Countisbury avenues.

Clear Stream ran south through Clear Stream Pond, under Merrick Road, and traversed the West End. It continued southward, defining the western border of the Green Acres Mall and Mill Brook community. Crossing Rosedale Road, it joined Hook Creek, before emptying into Jamaica Bay. Today, the stream is a dry valley through the West End and the mall; it re-emerges, however, between Riverdale and Southgate roads in Mill Brook.

Gatehouse, branch conduit, and aqueduct:

A gatehouse was erected on the southeast corner of the pond. The house protected the sluice gate, which controlled the water’s flow; and the spillway, which redirected excess water. A 24-inch branch conduit was installed at the pond, releasing a minimum of 750,000 gallons of water into the pipeline each day. The conduit ran south, parallel to Clear Stream’s path through the West End.

The conduit ended near Fir Street, close to where the rail stands today. (The rail didn’t exist at the time; it was built a few years after the construction of the waterworks.) There it joined the Ridgewood Aqueduct, which ran east to west. The aqueduct, over nine feet in diameter, transported the water to a pumping station in Brooklyn. Steam-powered pumps forced the water up through a tube to the man-made Ridgewood Reservoir that sat atop the Harbor Hill Moraine the northern moraine of Long Island. The elevation of the reservoir was important, as it had to be well above the highest dwellings and buildings in order for the water to flow down through the pipes via gravity.

Moraines and Valleys:

Valley Stream lies south of the Ronkonkoma Moraine. The moraine runs horizontally through the middle of the island it’s referred to as the backbone of Long Island. A geological expression, it was formed during the Wisconsin glaciation 21,000 years ago (Harbor Hill was formed not long after). The ground below the moraine is glacial out wash; it slopes downward, making it ideal for gravity-fed conduits.

Most valleys on Long Island’s south shore are outwash plain valleys; created by streams during the melting of the Ronkonkoma Moraine glacier. A dry valley refers to a valley that no longer has a preserved stream channel. Headwaters at the northern ends of valleys typically run dry but may temporarily fill during heavy rains. Water is more common at their southern ends, where the valley intersects the water table.

The northwest stream that was once attached to the northern rim of Clear Stream Pond is now a dry valley as is the headwater of Clear Stream. Clear Stream south of Merrick Road is only partially dry it’s dry through the West End and the northern half of the Green Acres Mall. It joins Hook Creek at Rosedale Road, before entering Jamaica Bay.

By 1877, the pond faced criticism. From The Brooklyn Daily Eagle: “The water did not look as clear as the other lakes, being spotted with green scum.” The pond’s pollution, “created by the population on their watersheds,” included muck and debris. A hand-drawn map entitled “A Map of Valley Stream about the Year 1880” (drawn by locals in the 1940s) labeled the pond with a racially inspired moniker (not uncommon at the time); named so, it is believed, because of its murkiness and degradation. Things were not looking good for the water works’ littlest pond.