Looking to get ahead of the addiction problem

Opiate epidemic compels local schools to critique their curricula

As of March 2017 the New York State Department of Health data shows that deaths attributed to opioid overdose in Nassau County decreased from September of 2015 to the same month in 2016. However, outpatient emergency room visits for all opioid overdoses have risen. Some activists are now calling for schools to step up their curriculum in regards to drug and alcohol prevention, and the state’s Education Department is providing some of the tools to do that.

This past June the State Education Department sent out a 39-page resource with information about appropriate grade level content. The packet includes what lessons the state believes is proper for each level, elementary, middle and secondary.

Dr. Anne Pedersen, the superintendent for the Lawrence School District said that health class is required of both middle and high school students, and in those classes they delve into drug and alcohol prevention. For this issue younger students will, “Focus on social-emotional learning,” she said, “that includes things like self and social awareness, responsible decision making and relationship skills.”

Some still argue that this hasn’t done enough to curb the opiate epidemic. Some parents of children who have died of overdoses have said the schools should do more to make children more aware of the consequences of opiate use, even scare them.

John Venza, the vice president of Adolescent Services at Outreach, a nonprofit organization headquartered in Queens, that helps people address the issues that stem from substance abuse, believes that isn’t the way to keep kids off of opiates.

Venza has worked with youths with these issues for 35 years. “Research shows scare tactics don’t work very well,” he said. “How many young people are attending the funerals of other young people? If that’s not scaring kids away from using what would?”

Outreach uses a different model; they try to work with schools and families to find long-term solutions to opiate abuse. “You need to give people the skills to survive without relapsing … creating a strong partnership between the kids, the counselor, the school and the family is the trick,” Venza said.

He highlighted that there is no one answer. “Different districts need to respond in different ways, most have embraced this issue,” Venza said. “Can the schools do more? Yes. Do I believe they want to do more? Yes.”

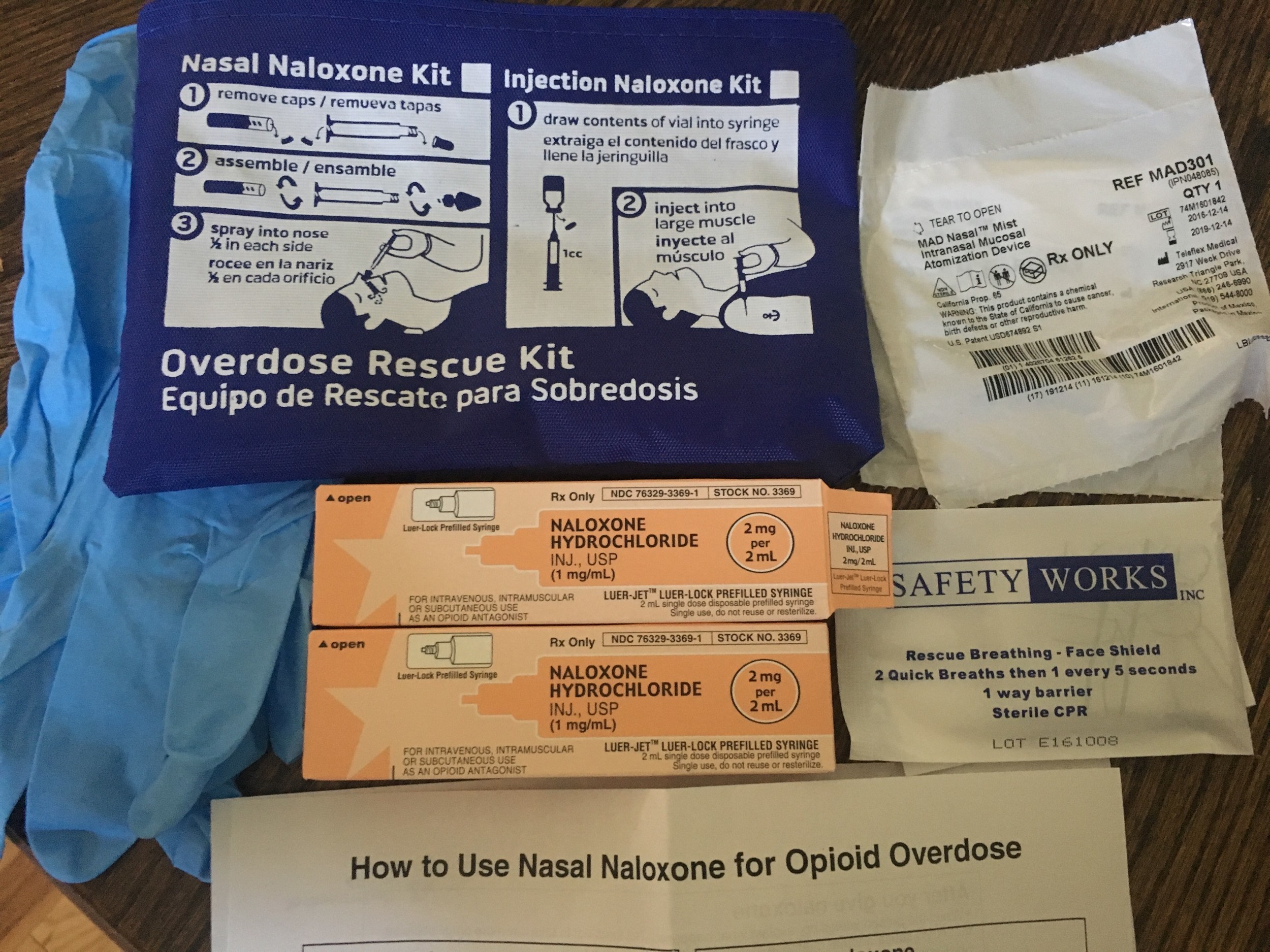

The Hewlett-Woodmere School District is planning on providing training opportunities for its nurses and staff members who would like to take part, said Deputy Superintendent Dr. Mark Secaur. “This training will allow them to administer an opioid antagonist such as Narcan to individuals at school, or at a school event, with signs of overdose in accordance with the law,” he said.

Narcan, which is also known as Naloxone, is a medication that blocks the effects of opioids, potentially halting an overdose. It isn’t a long-term solution, but both Suffolk and Nassau County police departments have reported a higher rate of Narcan administration, so it’s possible that the increase is at least partially responsible for the decrease in deaths attributed to overdose.

Training its staff to administer Narcan is a step that could save lives, and Hewlett-Woodmere is also ready to embrace any changes suggested by the state Education Department. “We will review our current curriculum to stay abreast of all developments in this area,” Secaur said.

Pedersen expressed a similar sentiment, and also added, “It’s important to remember no one chooses this path, they find themselves on it and can’t get off.”

47.0°,

Overcast

47.0°,

Overcast