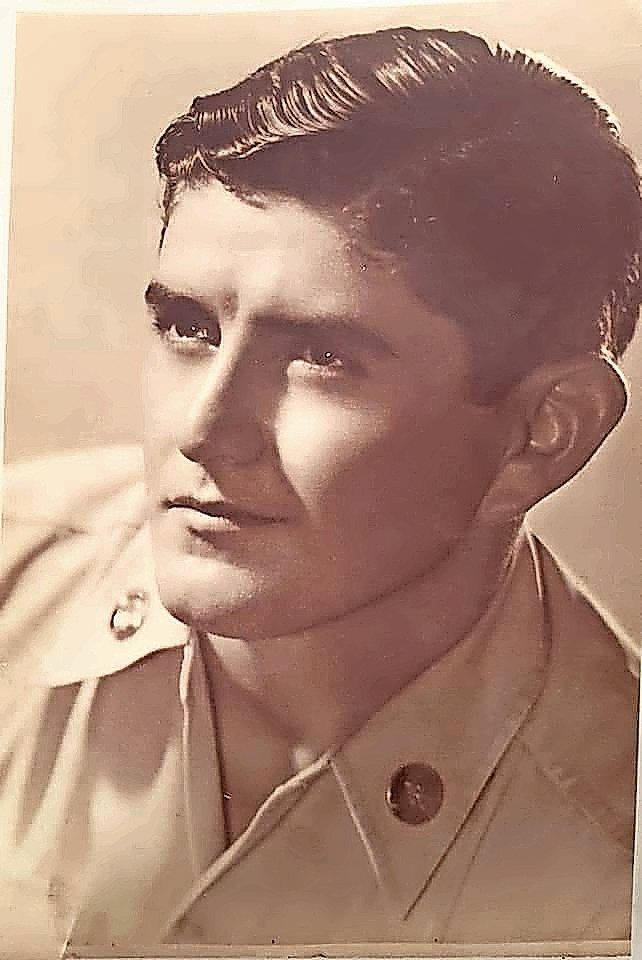

Edward Olvera still has strong grip at 100

Burma is a long way from South Bronx

Eddie O was watching Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers on the silver screen when his life changed forever.

He was sitting in a Bronx theater on Dec. 7, 1941, when the manager interrupted the film to tell the audience the Japanese had just attacked Pearl Harbor.

As he sat there, Edward Olvera overheard others asking each other, “Where the hell is Pearl Harbor?”

The answer to that is something Olvera would soon find out.

The next day Dec. 8, 1941, at James Monroe High School, senior Olvera and the class listened into to a broadcast by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt asking Congress to declare war on Japan, the members agreed and applauded the Declaration of War.

Five months before graduation, Olvera enlisted in the United States Army on Dec. 27, 1941, much to his parents’ dismay. They wanted him to be the first in the family with a high school diploma.

Olvera turned 100 years of age on Aug. 26, making him one of the few remaining World War II veterans from the Greatest Generation. This feat was celebrated and honored outside of his home in Baldwin Saturday, when the American Legion Post 246, Baldwin Fire Department, veteran motorcycle groups, Nassau County Police Department, alongside local politicians drove by his house wishing him a happy birthday and “thank you” for his service.

His service is well documented in a brief memoir dictated by Olvera and written by his daughter and caretaker Anne Garsia. It says how he left New York City shortly after enlisting as a poor teenager from the South Bronx, traveled thousands of miles across the world in four years to fight in the China-Burman-India Theater and return to tell the tales.

Talking to Olvera, he still conveys the emotion of leaving his family behind to courageously fight for the county.

“Was I scared? I was petrified, I was too scared to realize that this was for real and thank God my stepfather was there to give me the courage before I left,” he said, saying his stepfather gave him the valuable advice of never being late for training.

Assigned to the 683rd AA/AB Company, he traveled across the world, first landing in the Indian province of Assam. There he was given an anti-aircraft gun to help the war operation later known as “Flying the Hump.” Here is where he had his first taste of war. The operation was for the U.S. “fly boys” to pilot the eastern end of the Himalayan Mountains to resupply the Chinese war effort.

At “Hotel Hilton,” a bamboo hut Olvera stayed in with five other men, they were officially “blooded” on Valentine’s Day, when early in the morning they heard the screech of the air raid siren. Flying overhead were 29 bombers dubbed Zeroes firing on planes and buildings on the ground. Olvera sprang into action, firing his submachine gun till it was red hot and then some. When it was over, Air Force personnel told the men they had shot down six Zeros.

“All this action took place within ten minutes, and then it was suddenly over. All that was left was smoke from the burning planes and buildings,” reads the memoir. The shot down planes were good for one thing to the men, cooper, which was used to help run the alcohol stills.

At the end of 1943, they prepared for a new moment, rumors said it would be to Europe or even back home, but the answer was Burma. In Burma, not only did Olvera feel the constant threat of war, but the threat of nature, which was a pressing struggle.

It would rain for days and weeks at a time, swarms of mosquitoes and snakes would descend on the men and native animals like tigers and elephants would wander into their camp. In the memoir Olvera reflects on this, “The tigers especially love rubbing against our canvas tents. The(y) rubbed in order to get lice and ticks out of their fur. They were more frightened of us than we were of them.”

Across the world, sitting on raw wooden planks in the middle of the jungle he sat again watching Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers and Betty Grable sing and dance from a projector, now with a new perspective on the world.

Months passed in the jungle, morale diminished, and Christmas passed in 1944 without celebration. That was until a month later when a cargo plane could be heard from above. Suddenly, in record time, men were unloaded their packages containing food, beer, letters and other goodies. Kenny, a friend of Olvera, had a particularly interesting gift. He received a quart bottle of Ovaltine, with something else inside – a bottle of Brandy. Brandy was the secret Kenny’s parents sent over to their son and that the men shared. “It wasn’t long before we were very, very happy,” Olvera remembers.

In April 1945, the men were preparing to relocate again, when they heard honking. Searching for the noise, they saw officers waving and shouting. Olvera thought they were drunk from the night before, but the shouts were telling the men they were going home. It was over.

“Some men, myself included, broke down and cried. No one slept that night. All we could think about was that we were going home. We had the survived the horror of this awful place,” the memoir tells.

A day or two later they were flown to Calcutta and taken to an encampment in the middle of the city. It was the same day that Germany surrendered and the war in Europe was over. Once home, he took a half-priced Yellow Cab to his parent’s house in the Fordham area, the discount given for his time spent oversees. Screams of delight, “It’s Eddie, Mi hijo, gracias as Dios” rang from his happy mother. The war was over, but Olvera would reenlist in the Air Force, spending nine years all together in the service of America.

He moved to Baldwin in 2004, working after his years of service as an insurance adjuster. Olvera’s secret to a long life is walking, eating healthy, and not smoking cigarettes.

Do you have thoughts about this aritcle? Send them in to kkovac@liherald.com

39.0°,

Fair

39.0°,

Fair