George Grosz’s groundbreaking series on view at Heckscher Museum of Art

Perhaps, there is nothing more symbolic than the “stick man.” We see it on signs, in sketches, in games.

George Grosz, a German-born artist, takes a different symbolic approach with his “Stick Men” series to ponder a post-World War II landscape.

Born in Berlin, Grosz’s political art offered a strong commentary on the German government following World War I. After observing the horrors of war as a soldier, Grosz became involved in pacifist activity, publishing drawings in satirical and critical periodicals — also participating in protests and social upheavals. His drawings and paintings from the Weimar era sharply criticize what Grosz viewed as the decay of German society.

His art was branded “degenerate” by the Nazi regime due to Grosz’s criticism of Hitler and aggressive nationalism.

The Heckscher Museum’s current exhibition, “George Grosz: The Stick Men,” brings the artist’s works “home.” Fleeing persecution, Grosz and his family left Germany and arrived in Queens in 1933, eventually settling in Huntington in 1947. He became an American citizen in 1938, and lived in Huntington until shortly before his death in 1959.

Seventy-five years later, Grosz’s warning against fascism and global conflict is as relevant as ever, according to Karli Wurzelbacher, the museum’s chief curator, and exhibit co-curator.

It was in Huntington — and in response to the harrowing atrocities of World War II — that Grosz created the Stick Men, his last major series of works. The series represents starved beings wandering aimlessly through a polluted, post-apocalyptic world. In search of food and shelter, these victims of adverse circumstances in turn become perpetrators themselves.

Writings of the period portrayed Grosz as living a suburban and apolitical life in America, in contrast to his earlier fierce political art in Germany. The opposite is true: his Stick Men series culminates his lifelong political and artistic struggles.

“Stickmen are these abstracted figures who are really dehumanized. They are skeletal, they are transparent, we can see right through them,” Wurzelbacher says. “I don’t even know if you could say they’re people anymore. They are beings who have lived through this period of time, and really have kind of forfeited their humanity.”

The exhibit makes its way here from Das kleine Grosz Museum in Berlin, Germany, a museum dedicated to the career of this important artist. Curator Pay Matthis Karstens and co-curator Alice Delage organized the original exhibit, which includes works from The Heckscher Museum and European public and private collections.

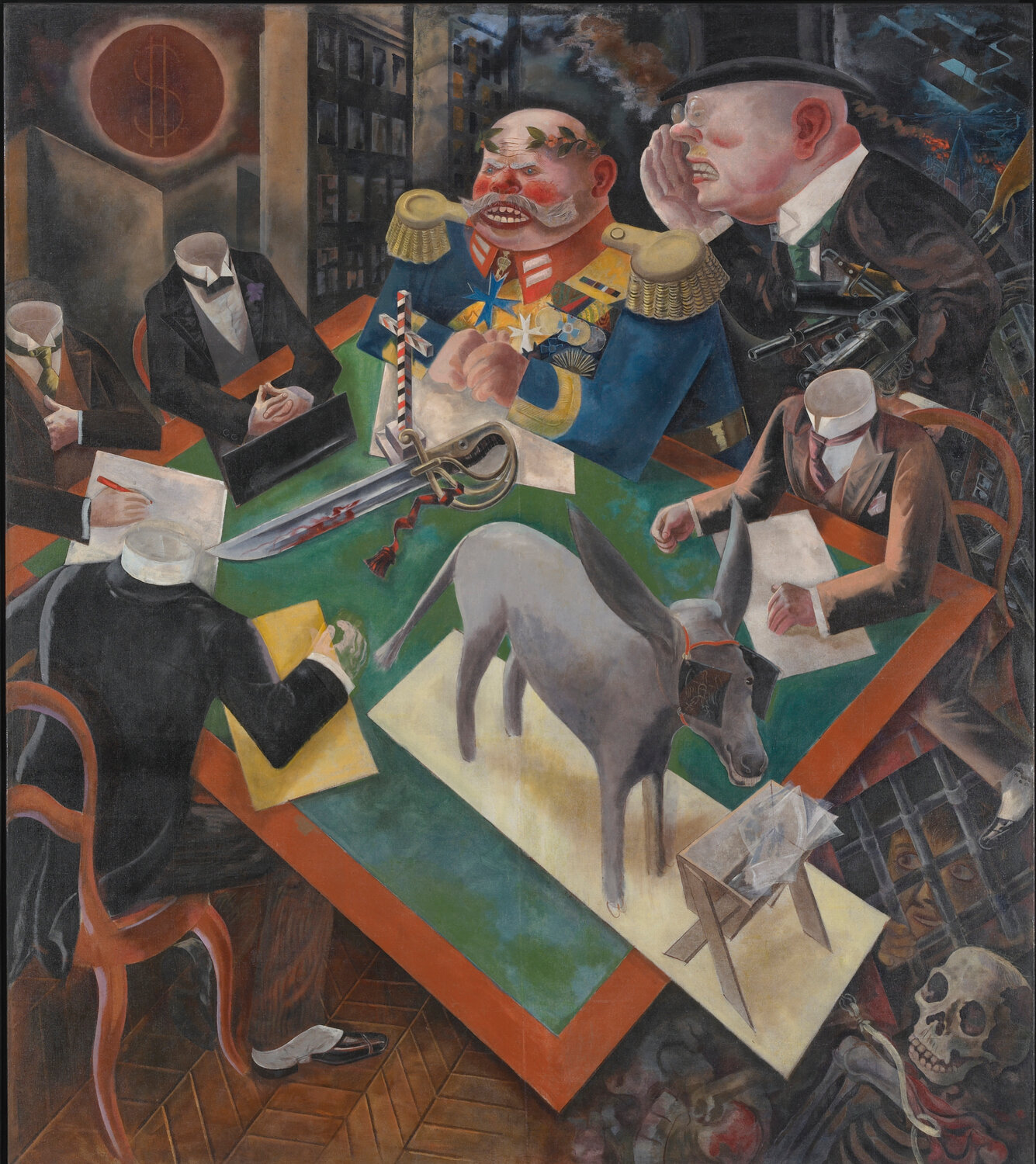

Now it’s arrived at Heckscher in an expanded version, featuring additional works from its own collection, including Grosz’s 1926 masterpiece “Eclipse of the Sun.” The painting, done while he was in Berlin, is almost prophetic in nature, telling of the turmoil leading up to World War II. The scene depicts headless German bureaucrats at a conference table being influenced by militarists and industrialists.

“It’s called ‘Eclipse of the Sun’ because, in the upper corner, a dollar sign has eclipsed the sun,” Wurzelbacher says. “The sun — the symbol of life, health and nature — is being eclipsed by capitalism, war and greed.”

Grosz uses watercolors to show the emotional hollowness of the characters, employing thin washes to show faded husks of humanity.

“Watercolor as his choice of medium helps communicate what the stickmen are,” Wurzelbacher adds. “He also kind of splatters the canvas with flecks of paint that can look like mud or blood.”

The series gives us insight to Grosz’s own experiences. Another work, “Painter of the Hole,” shows a stickman artist painting a hole on the canvas in front of him.

“He is surrounded by such a loss of meaning that he doesn’t even know what to paint, and all he can paint is this emptiness,” Wurzelbacher says.

Ensconced in the United States during World War II, Grosz’s art demonstrates the impact of war separated by an ocean.

“There’s this thinking that because Grosz was on Long Island, he was somehow separate from what was happening in Europe,” Wurzelbacher explains. “We wanted to make the case that that wasn’t true, that the war did touch his life and touched the lives of many Long Islanders.”

Visitors to the museum will have free access to this and all other exhibits, continuing the legacy of founders August and Anna Heckscher. A Bank of America grant enables Hecksher to offer free admission into 2025, welcoming more visitors and families to enjoy art and community.

Of course, donations are always welcome.