How did this Holocaust survivor create a kids' version of her Holocaust tale?

The story of Holocaust survivor Marion Blumenthal Lazan has been written again, but this time, catered to younger generations. Karolin Greis flew from Germany to New York to present Blumenthal Lazan with the refigured work.

Greis, a seventh grade teacher at the Marion Blumenthal Hauptschule, in Hoya, Germany led her students over the course of a year in reworking Blumenthal Lazan’s story, originally written by Blumenthal Lazan and Lila Pearl.

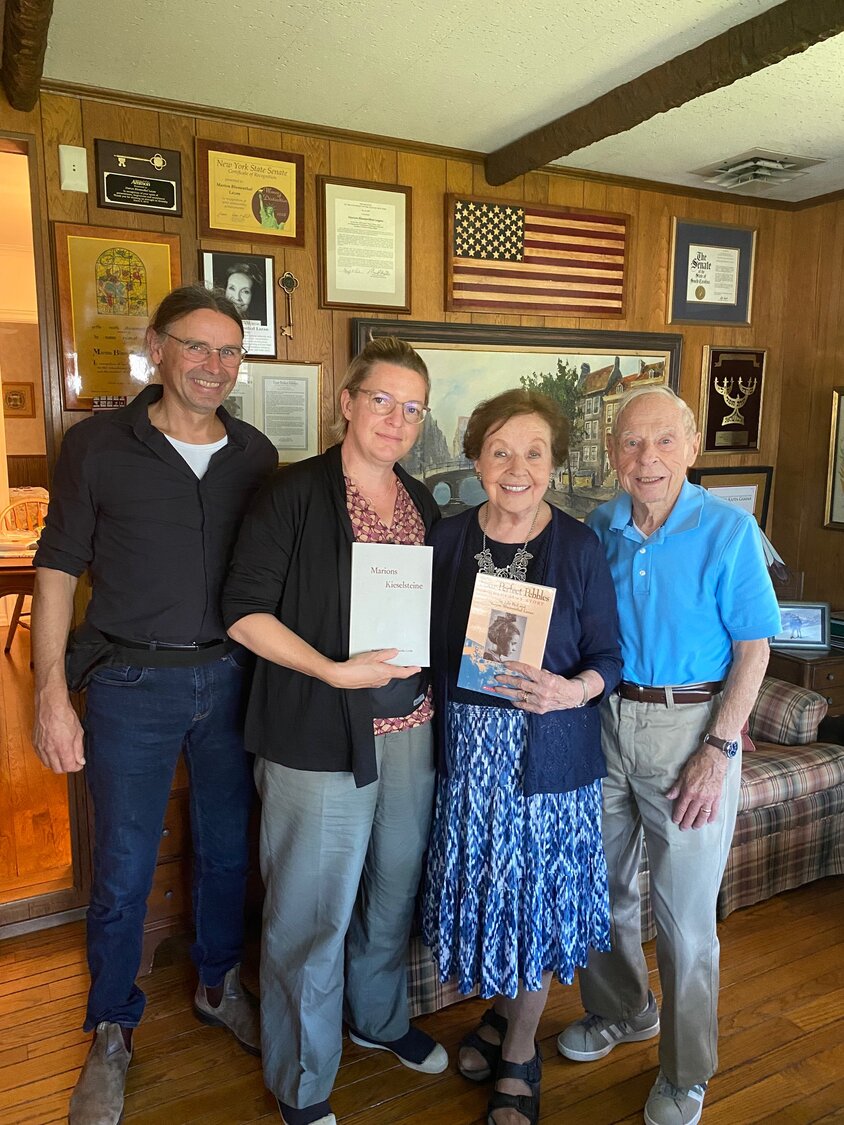

The goal was to make something comprehendible for young minds. On Aug. 31, the teacher and her husband, Christian Greis visited the Hewlett home of Blumenthal Lazan and her husband, Nathaniel Lazan, to present the handcrafted text.

“This would not have happened if her heart wasn’t in it,” Marion said of Greis.

The two met in 1996 when Marion spoke at the school where Greis was student teaching, named in the survivor’s honor.

When Greis started her professional career, she saw that students were struggling to understand Blumenthal Lazan’s story as told in her memoir, “Four Perfect Pebbles.” While the text had been translated into multiple languages and presented in flashcards for younger readers, Greis found that students were having trouble with the vocabulary and were missing meaning in the book.

The teacher, feeling deep sadness at the start of the war in Ukraine, was inspired to ensure that students understood Blumenthal Lazan’s story to increase their awareness of history and help to prevent other instances of violence.

Greis collaborated with Michael Linke, the owner of a print museum in Hoya, called Museumsdruckerei Hoya, to create the new book, “Marions Kieselsteine” translated to “Marion’s Pebbles.” The museum property, to Greis’ surprise was directly behind Blumenthal Lazan’s childhood home.

Greis wrote out simple sentences and students aligned lead letters to produce 480 copies of this 41-page book.

“It’s not specialized for books because we only have one box of small letters and you could make six of these pages and then the letters ran out,” Greis said of the printing equipment. “We had to put them back in the box and then make the new ones again and again and again, it took us quite a while to make all of those pages.”

When Greis arrived at Blumenthal Lazan’s home to give her the book, along with her favorite German candy, the Holocaust survivor said she was astonished with the effort, imagination and perseverance that went into bringing this text to life.

“Their little hands worked on this, letter by letter by letter,” Marion said.

She expressed gratitude for the small details, like the four small pebble carvings on the front cover of the text. Marion immediately asked how the text could be translated to English for further distribution.

Marion was most appreciative that Greis was continuing to educate students, especially in Germany.

“If you want to make this a more peaceful world, there’s such as thing as understanding today’s generation had nothing to do with what happened then and they bend over backward to set things right,” Marion said. “Sharing the story, only then will they understand and realize the importance of the lessons learned from that dark period of our history.”

54.0°,

Fog/Mist

54.0°,

Fog/Mist