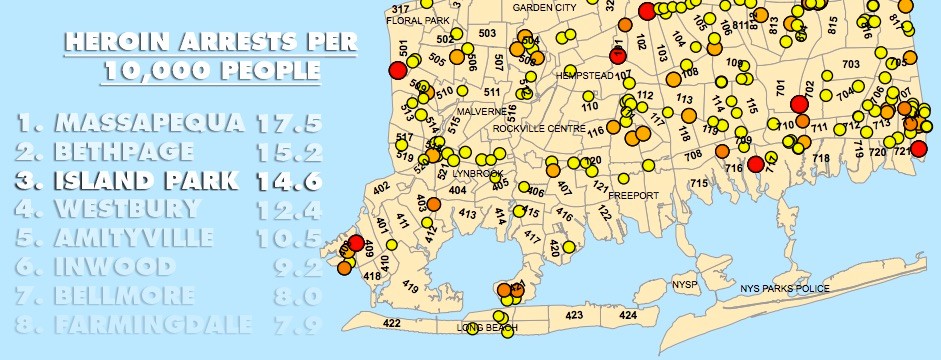

Island Park has third-highest rate of heroin arrests in county

‘This drug affects everybody’

“It comes in waves.”

James Miotto, Island Park’s fire chief and an emergency medical worker, said the Fire Department gets called to the scene of a heroin overdose as frequently as four times a week, although, he added “When it slows down, we get [one] every two weeks.”In the first six months of 2017, there have been nearly twice as many heroin arrests in Island Park as there were in all of 2016, according to data provided by the Nassau County Police Department. “There’s definitely an influx of heroin,” Miotto said. “I don’t know about doubled, but it’s definitely increased.”

In mid-June, Lt. John Owen of the 4th Precinct spoke at a public meeting of the Island Park board of trustees about a policing tactic in which officers, responding to a tip from a community’s local officials, “saturate” the area. The night before the meeting, this method led to 15 arrests in Island Park and nearby neighborhoods.

According to Miotto, “When people get arrested, overdoses slow down.”

“They need to be educated about the Good Samaritan laws,” Dolan said. Under New York’s 911 Good Samaritan Law, anyone can call 911 “without fear of arrest if they are having a drug or alcohol overdose that requires emergency medical care or if they witness someone overdosing,” according to the state Department of Health website.

The police data also shows that Island Park has the third- highest rate of heroin arrests per capita in Nassau, behind Massapequa and Bethpage. Although there are fewer total arrests than in larger communities, Island Park’s arrest rate is about three times higher than the average among communities with less than 10,000 people.

According to Dr. Josh Kugler, South Nassau Communities Hospital’s chairman of emergency medicine and director of emergency services, statistics like these aren’t useful for answering questions such as, why Island Park?

“This epidemic is non-discriminatory,” Kugler said. “This drug affects everybody.” He added that data like the heroin arrest statistics are put to better use answering questions like, where will resources be most effective in fighting this epidemic?

Narcan

Many local medical facilities are hosting training sessions that teach people how to use a potentially life-saving overdose remedy called, naloxone, or Narcan. Kugler said that this medicine, in the form of a nasal spray, temporarily stops the progression of an overdose, noting that it has been an invaluable tool in the fight against opioid overdoses.

“Before, we used to get a lot of patients who were overdosed to the point of [being] brain dead by the time we could get them resuscitated,” Kugler said. Now, he noted, “We’re able to do more for individuals” treated with Narcan before medical assistance arrives.

Treatment

But overdoses are only one part of this epidemic. In fact, Dolan describes the condition of many addicts as “between overdoses.” He said that one way to break the cycle is to change a part of New York state’s mental hygiene law, called Kendra’s Law.

Under the statue, those with severe mental illnesses who pose a threat to themselves or the community can be compelled by a judge to take medication, or be forcibly institutionalized.

Dolan said that opioid addiction is a severe mental illness, but isn’t treated that way under the law. After an overdose, he explained, addicts are released to the care of their parents or other relatives, who don’t have the understanding or skills necessary to deal with an addict. “Kendra’s Law should be expanded to include addicts,” Dolan said, adding, “It’s well understood that coercive methods are useful for getting people into treatment.”

According to Dr. Genevieve Weber, associate professor of counseling and mental health professions at Hofstra University, the disease doesn’t stop with the addict. “It’s a family disease,” she said.

Often, the family wants to keep the situation quiet. “We don’t want to admit it,” Weber said. “We don’t want to bring outsiders into the circle.”

Hospitals and police stations can serve as opportunities to get addicts into treatment, she said, adding, “When they’re under the influence, there’s no talking to them.” But a brief detox could provide a window.

Weber agreed that coercive methods could help families get their loved ones the help they need. “Prison is one of the biggest mental health providers in the country,” she said. “If there was some law in place, where someone was in a place of desperation, to get them, in an involuntary way, into detox. Once they’re in a treatment program,” that window of opportunity widens.

Most important, she said, the treatment window must be kept open. “I’m a fan of any harm-reduction approach,” Weber said of needle exchanges or "shooting galleries," where professionals can monitor addicts, and offer them information on treatment, in addition to medical attention, should they need it.

Such harm-reduction approaches have been widely criticized as “enabling” the problem, but Weber doesn’t see it that way. “As long as you can keep these people alive,” she said. “You’re increasing the chance that you’ll be able to reach them.”

41.0°,

Fair

41.0°,

Fair