Seaford a hotbed of bootleggers during Prohibition

Town historian Fred Roth details revelations of rumrunners and speakeasies

In January of 1920, with the passing of the Volstead Act, the United States of America enforced the ratification of the 18th Amendment, banning the manufacturing, transportation and sale of alcoholic beverages. Notoriously, many Americans resisted Prohibition. From making homemade tipple in bathtubs, or “bootlegging,” to the gathering of people to drink at secret speakeasies across the U.S., taking illegal measures to consume alcohol was commonplace, especially on Long Island’s south shore.

“There were a lot of baymen that were rum-runners,” said local historian and longtime Seaford Fire Department member Fred Roth, 90, of Seaford. “No one [here] ever become a millionaire from it, but they did it for money.”

“Baymen,” Roth explained, were usually men who made a living from catching and selling seafood and ducks, off the southern coast of Nassau County. At the start of Prohibition, though, they pivoted towards another more lucrative moneymaking endeavor.

Roth, born in 1929, was the youngest member of his family. He was only 4 when Prohibition came to an end, but he recalls hearing stories from local Seafordites, especially his fellow Seaford Fire Department members.

When Prohibition was passed in 1920, locals used any outlet available to them to attain alcohol. One of the most prevalent was placing “orders” with baymen, who took their 40-foot boats 3 nautical miles off of Seaford’s south coast, where Canadian cargo ships holding cases of alcohol waited outside U.S. territorial waters. After retrieving the alcohol, baymen would return through Rockaway Inlet, Fire Island Inlet or Jones’ Inlet and into the Great South Bay. Being familiar with the area, baymen were able to navigate through the bay and its many small barrier islands.

Roth was told tales of how baymen would frustrate U.S. Coast Guard vessels.

“They were able to get away from the feds when they were in the bay,” Roth said. “They’d drop the booze off at ‘bay houses’ where it could be hidden.”

Bay houses were small outposts, usually hidden throughout the barrier islands, where alcohol was stashed for those who ordered it. Baymen did consistent business with speakeasies, and there were two in the town of Seaford. Before Robert Moses spearheaded the project to fill in most of Seaford’s creeks to transform its barrier islands into larger landmasses, many narrow channels separated the town. Both of Seaford’s speakeasies were located on Ocean Avenue, directly across from Cedar Creek and running perpendicular to Island Creek. Today, locals know the area as Cedar Creek Park, which takes its name from the East Bay inlet that still runs north almost to Merrick.

The most popular speakeasy in the area was known then as the Sea Breeze Inn, in Wantagh. The former beach house inn rented fishing rods and small canoes to families and served food to beachgoers by day.

“You could get a meat dish, a seafood dish or a fowl dish,” Roth said. “And then at night, you could get a rye, a scotch, whatever you wanted.”

The inn stood almost exactly where the swimming pool in Wantagh Park is now. Roth recalls going there often with his family to rent boats on warm summer days.

A member of the Seaford Fire Department for more than seventy years, Roth admitted that many members of the department were also baymen. He himself spent many days on the bay, but never considered himself a true baymen.

“You had to make your full living on the boat to be considered a baymen,” Roth said. He became a local union plumber after plans to go to college were nixed rather fast. He wasn’t able to afford college, because of the Great Depression.

In total, Roth said there were about 50 local Seaford baymen.

Roth also mentioned that although speakeasies were popular during the time, many Seaford and Wantagh locals were not particularly big drinkers.

“They’d drink socially,” Roth said. “It was the people who came from the city who were visiting Long Island who were really were the drinkers.”

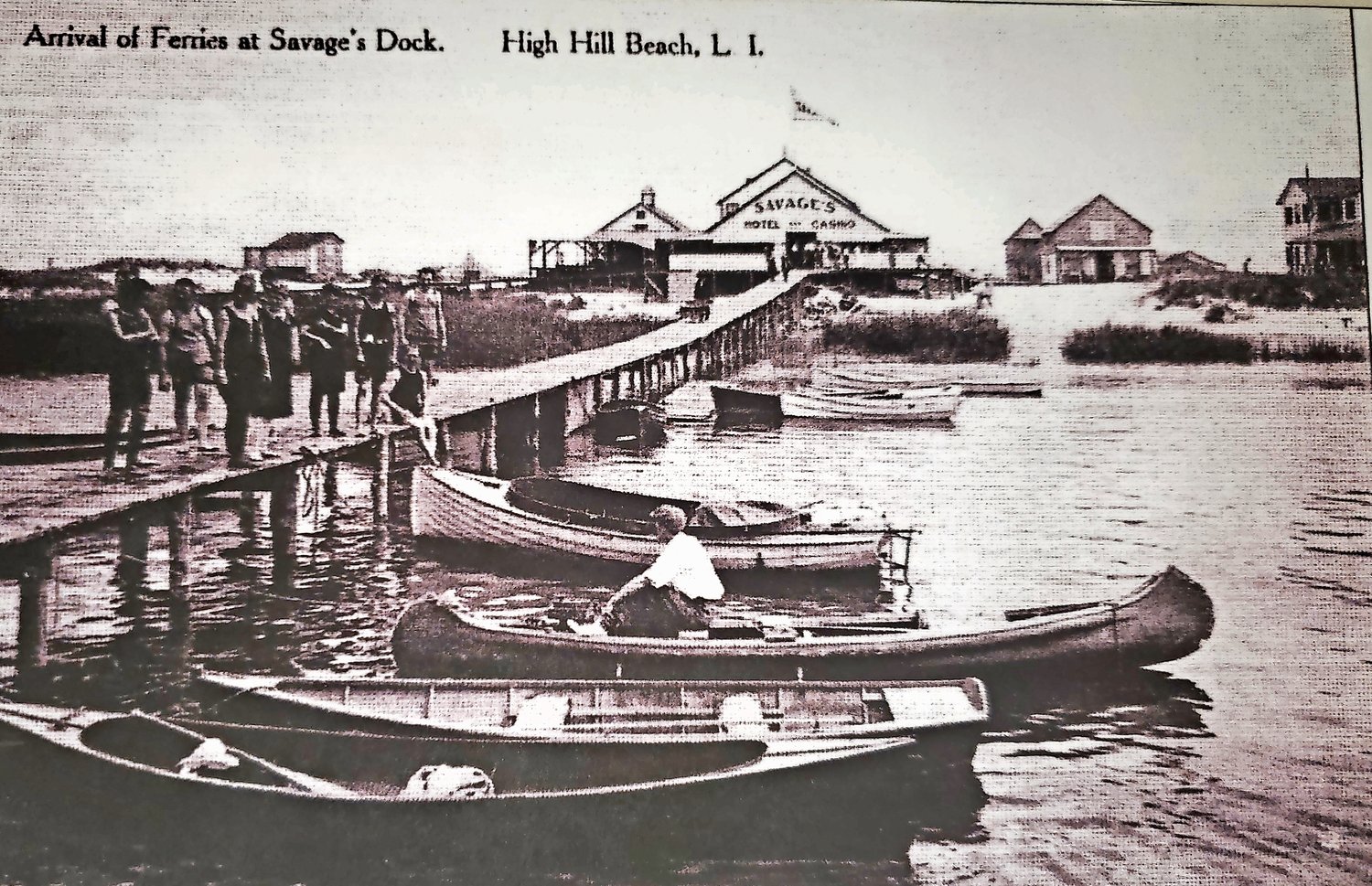

He continued, detailing stories about wealthier city folk coming to Long Island to get away. One of their “outposts” was High Hill Beach. The secluded Jones Beach mini-commune on Zach’s Bay was a rich man’s retreat, Roth said. Summer homes were erected, and one of the bay’s most prevalent speakeasies sat just feet away from the dock – Savage’s Hotel.

“Baymen would take people to High Hill Beach,” Roth said. “The feds didn’t really have boats that could get there.” He explained that Coast Guard boats didn’t have the motor power to make it past the currents and to High Hill’s dock at the time, making it a safe haven for drinkers. Seaford was one of only two coastal towns that were able to shuttle people back and forth.

Roth was candid when asked why people, especially Long Islanders, went to such lengths to attain alcohol.

“It wasn’t about the booze, really, it was bigger than that,” Roth said. “If you have something and someone takes it away from you and says you can’t have it anymore, that was wrong to a lot of people. It was an injustice they were going to fight.”

Roth mentioned that people didn’t receive much news about Prohibition from the government at the time. He remembers getting the majority of his news from radio programs. Beyond that, people were mostly in the dark.

The 21st Amendment was ratified in 1933, and Prohibition came to an end. Baymen, for the most part, returned to catching seafood. However, in an effort to complete his highway connecting Long Island to Jones Beach, Robert Moses ordered many of Seaford’s creeks to be filled in.

“That was basically the end of the baymen,” Roth said. “There were really no more of them by the late 1930’s, early 1940’s.”

None of Seaford’s speakeasies still stand today. Its iconic creeks, traversed by many a baymen, are now filled in with dirt and gravel. Its demographics have changed. But its history still lives on. Inside a small yellow house on Seamans Neck Road, Roth sat for a moment. He removed his glasses and asked, “When I go, who is going to tell these stories?” He smiled slyly, looked down at the clippings of historical texts and maps he had collected and nodded his head. “Someone has to tell them.”

50.0°,

Overcast

50.0°,

Overcast