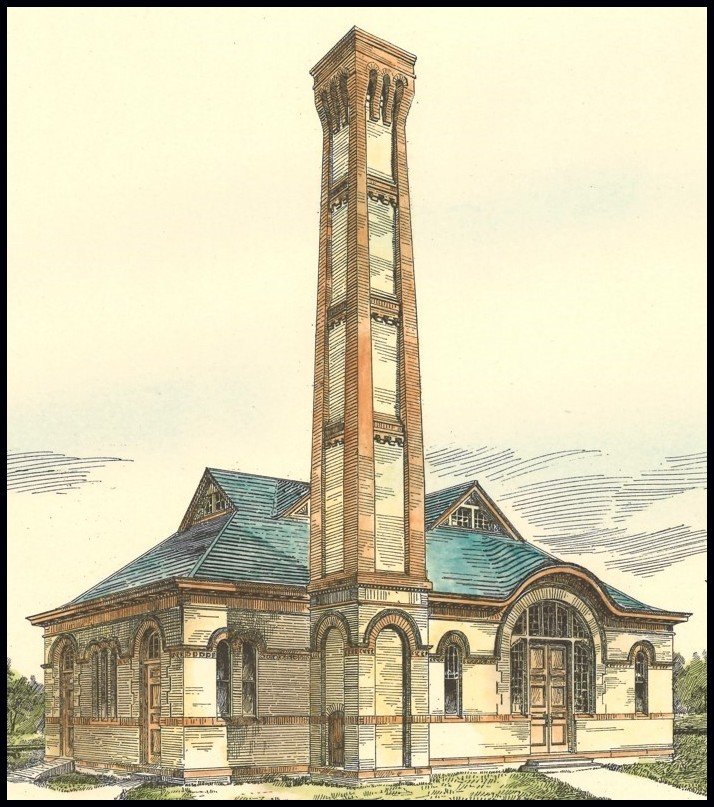

Clear stream pump station

History hidden in plain sight

The six ponds that dotted Merrick Road from Jamaica to Rockville Centre had a strong start and a weak finish. Up until the 1880s, they had done a splendid job of keeping Brooklyn hydrated: such a good job, in fact, that the borough’s population grew exponentially from more than 266,000 souls in 1860 to 566,000 in 1880. After that, however, the ponds had a hard time meeting their daily quotas.

New water sources needed to be found. Suffolk would not permit the pumping of the Pine Barrens, so instead of going east, the waterworks went south purchasing land in southern Queens (now Nassau County) to sink driven wells. From 1881 through 1897, 18 pumping stations were added to the water supply. Valley Stream’s Watts Pond (Mill Pond at Edward W. Cahill Memorial Park) and Clear Stream pumping stations opened in 1881 and 1885.

Clear Stream’s station, located north of Target on modern-day Sunrise Highway, was designed by Alfred D. F. Hamlin (1855-1926). Born in Turkey (his missionary father was a first cousin to Hannibal Hamlin, Lincoln’s vice president), Alfred came to the States at 15 to study history at Amherst College and architecture at MIT. He completed his education at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. A professor, and later, the director of Columbia University’s Architecture Department, Hamlin consulted on many public buildings, designing only a few, Clear Stream Pumping Station one of them

From the January 6, 1886 issue of The American Architect and Building News:

The Clear Stream station is faced with Croton brown brick. The woodwork is oak, except for the roof. The walls are painted a delicate salmon color, relieved by bands of dark red at the window arches, and wainscoting of enameled brick, while the ceiling is a shade of turquoise between the trusses. The masonry and roof were built by day labor. The cost of the building was about $9,000 to $10,000.

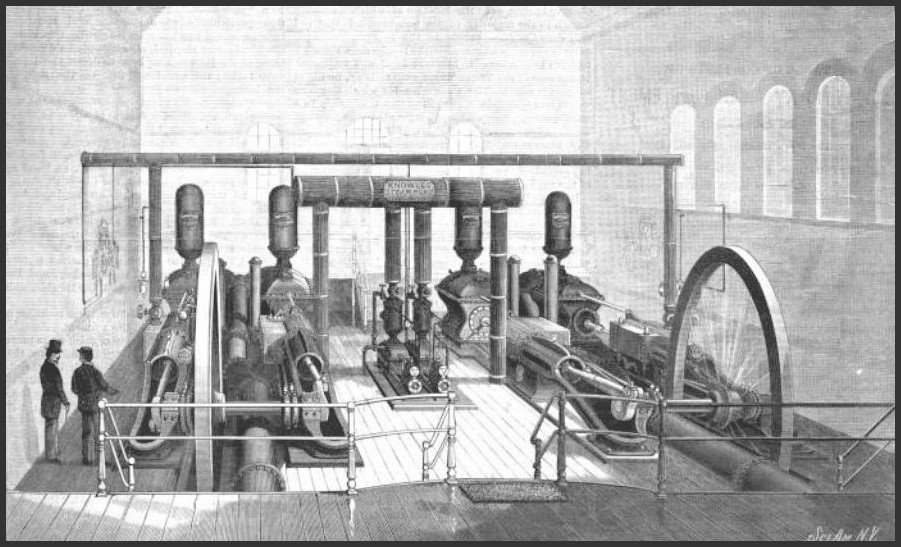

The pumping station’s 152 wells were laid out in two rows, spaced eight feet apart. A railroad spur, located at the foot of modern-day Midwood Street, made its way into the watershed each day. It carried the coal that fueled the steam-powered pumping engines.

In 1898, Brooklyn became one of five boroughs. Their water system was transferred to the City of New York. By then, Clear Stream Pond was shut down because of pollution and seawater invasion. Other ponds were abandoned, too, but were re-purposed as infiltration galleries horizontally placed wells that collect groundwater from the top of the upper glacial aquifer. Galleries are safer from surface contamination than wells.

In 1900, Frederick Reisert, who owned what is now the Green Acres Mall and the community of Mill Brook, filed a $60,000 claim with NYC. Reisert’s farm bordered the nine-acre watershed. Clear Stream and its springs ran vertically through his property. Through relentless pumping, the stream and springs dried up. Reisert could no longer irrigate his fields. His case made it to the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court. A few times. The last trial awarded Reisert $6,000 for injury to his property and $8,000 for the city’s right to maintain its pumping station.

In 1907, with much opposition from Nassau County, a 72-inch steel pipeline was constructed from Ridgewood to Massapequa its easternmost pond.

During World War I, the watershed was protected by soldiers; the perimeter was surrounded by a wrought-iron picket fence. Fencing, however, did not stop the local children from finding their way into the watershed. “We wandered about, picking berries for mother,” recalls Madeline Kappauf in a 1987 oral history recording. The youngsters would inevitably get caught and reprimanded by the soldiers. All was forgiven when they returned with freshly baked pies.

In late 1939, the city’s water supply was at a record low: drought the culprit. In 1940, to brace for a disaster that never came, the Dept. of Water Supply, Gas and Electricity built three nearly identical brick pump houses. A new station at Clear Stream replaced Hamlin’s masterpiece; it was located southeast of the original, in Target’s parking lot. A new Watts Pond Pumping Station also replaced an existing one. And, lastly, the Hook Creek Pumping Station was erected on the northeast corner of Sunrise Highway and Hook Creek Blvd.

In 1953, when the watershed was shuttered for good, NYC granted an easement to Valley Stream, allowing the Village to use the property as parkland. This was the scenario that transformed Watts Pond, Valley Stream Pond (Arthur J. Hendrickson Park), and Clear Stream Pond (Arlington Park) into the parks they are today. The Clear Stream Pumping Station, however, was not a suitable location for a park; it bordered Sunrise Highway, one of the busiest arterial thoroughfares on Long Island. The property was rezoned for commercial use.

In 1995, Vornado Realty Trust, a Roth enterprise, bought the interest formerly owned by Trump from Citicorp and took control of the company. Roth sold the lease to Caldor Corp. which demolished the building and built a smaller structure. It has been said that during the demolition, construction crews reputedly offered Knapp’s art to passersby as souvenirs. Caldor went bankrupt, and the property was sold to Target in 2000.

The pumping stations are long gone. Neither building was replaced; instead, the roadway covers each plot of land. On the north side of Target, there is a white picket fence that borders the parking lot. If it’s late enough, the lot will be empty. A beautiful void. The Japanese have a name for this: yohaku no bi. The beauty of empty space. The lot’s blankness, its nothingness, can transport us back in time. If you squint hard enough, you just might see the pump house, the neatly lined up wells, soldiers protecting a watershed, children picking berries, and a wrought-iron fence that looks much like the one that stands today.

41.0°,

Fair

41.0°,

Fair